Heavy-metal music is a surprising indicator of countries’ economic health

Popular music styles are often closely connected to the social situations where they first began. Rock ‘n’ roll grew out of the heady culture of American cities following the Great Migration and World War II, as formerly rural blacks brought rapidly evolving jazz and rhythm and blues into cities. Decades later, the disinvested inner cities of 1980s America helped foster the rap and hip hop that we listen to today.

Popular music styles are often closely connected to the social situations where they first began. Rock ‘n’ roll grew out of the heady culture of American cities following the Great Migration and World War II, as formerly rural blacks brought rapidly evolving jazz and rhythm and blues into cities. Decades later, the disinvested inner cities of 1980s America helped foster the rap and hip hop that we listen to today.

Heavy metal is a strange case, then. The music sprouted originally from working-class kids in economically ravaged, deindustrialized places like Birmingham, England. Even today, it seems to be most popular among disadvantaged, alienated, working-class kids.

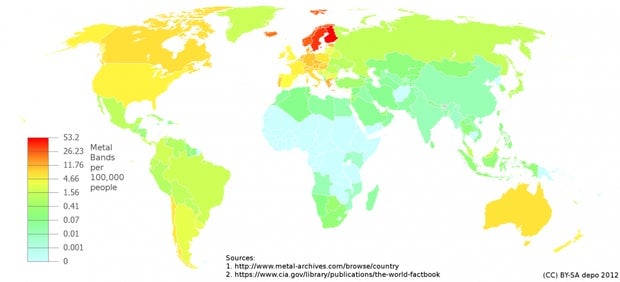

But take a look at the map below, which I wrote about two years ago, and have been thinking again about over the past couple of months. It tracks the number of heavy metal bands per 100,000 residents using data from the Encyclopaedia Metallum. The genre holds less sway in the ravaged postindustrial places of its birth, but remains insanely popular in Scandinavian countries known for their relative wealth, robust social safety nets, and incredibly high quality of life.

When I wrote about this map back in 2012, commenters had all sorts of explanations for why heavy metal spread so far north so intensely. Metal’s emotional darkness, some said, reflected northern Europe’s long, cold winter nights. The fury of the music and the violence of some of its lyrics resonated with Scandinavia’s pagan past, what with all those Viking raiders and Berserkers. One commenter suggested that the music correlated worldwide with high levels of alcoholism.

Indeed, a decade-old article by Mark Ames, “Black Metal Nation: What do Norwegian Dirtheads and Richard Perle Have in Common?” suggests that metal might be the adolescent id that is simmering beneath Northern Europe’s outwardly complacent façade. “Norway,” he wrote, “is not only a completely humorless society… but… a deeply oppressive society, in a recognizably bland, caring, pious, Social Democratic way.” Metalheads experience their boredom, he speculated, as “real suffering.” According to this logic, metal may instead be the product of affluent societies, a countercultural backlash for the privileged.

I thought it would be fun to dig a little deeper into the economic and social factors associated with the popularity of heavy metal across various nations. I’m not a metal head but have long been a Black Sabbath fan. They were the first rock band I ever saw in concert and I cut my teeth on guitar playing “Iron Man” and “War Pigs” in my middle school band.

So with the help of my Martin Prosperity Institute colleague Charlotta Mellander, I examined the connections between heavy metal and a range of economic and social factors. What we found may surprise you. Mellander, who is Swedish, attributes Scandinavia’s proclivity for heavy metal bands to its governments’ efforts to put compulsory music training in schools, which created a generation with the musical chop to meet metal’s technical demands. (As The Atlanticnoted last fall, this has helped the region excel in pop music as well). As always, I point out that correlation does not equal causation and points simply to associations between variables.

What we found is that that the number of heavy metal bands in a given country is associated with its wealth and affluence.

At the country-level, the number of heavy metal bands per capita is positively associated with economic output per capita (.71); level of creativity (.71) and entrepreneurship (.66); share of adults that hold college degrees (.68); as well as overall levels of human development (.79), well-being, and satisfaction with life (.60).

The bottom line? Though metal may be the music of choice for some alienated working-class males, it enjoys its greatest popularity in the most advanced, most tolerant, and knowledge-based places in the world. Strange as it may seem, heavy metal springs not from the poisoned slag of alienation and despair but the loamy soil of post-industrial prosperity. This makes sense after all: while new musical forms may spring from disadvantaged, disgruntled, or marginalized groups, it is the most advanced and wealthy societies that have the media and entertainment companies that can propagate new sounds and genres, as well as the affluent young consumers with plenty of leisure time who can buy it.

This post originally appeared at CityLab. More from our sister site: