What Europe can learn from the 1970s oil crisis: Don’t fear high prices

The price of Brent crude oil, the international benchmark, hit $125 per barrel on March 7, its highest point since 2012. Driven by market turmoil caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the price is about double what it was before the pandemic, and six-fold above its low point in April 2020.

The price of Brent crude oil, the international benchmark, hit $125 per barrel on March 7, its highest point since 2012. Driven by market turmoil caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the price is about double what it was before the pandemic, and six-fold above its low point in April 2020.

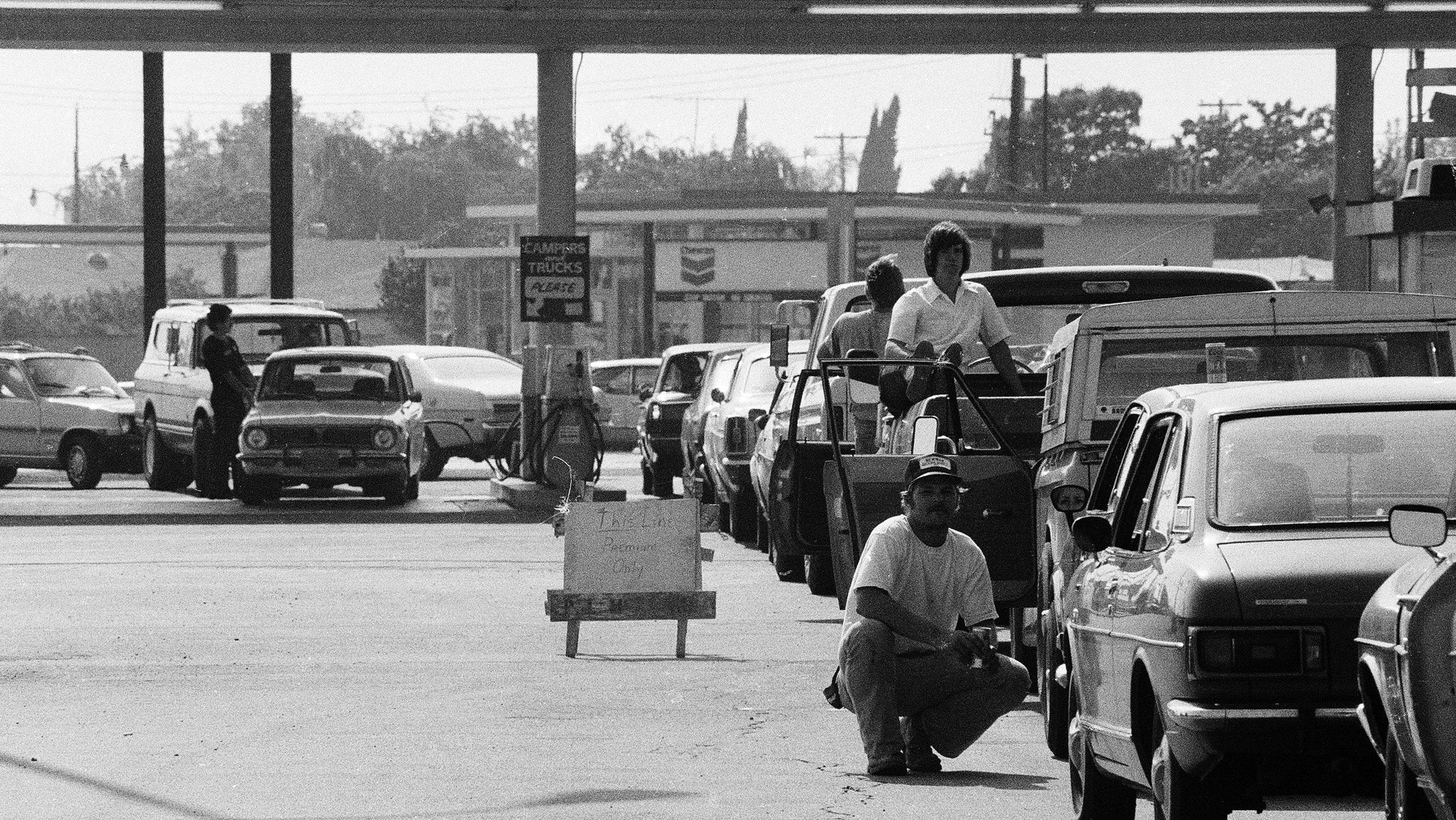

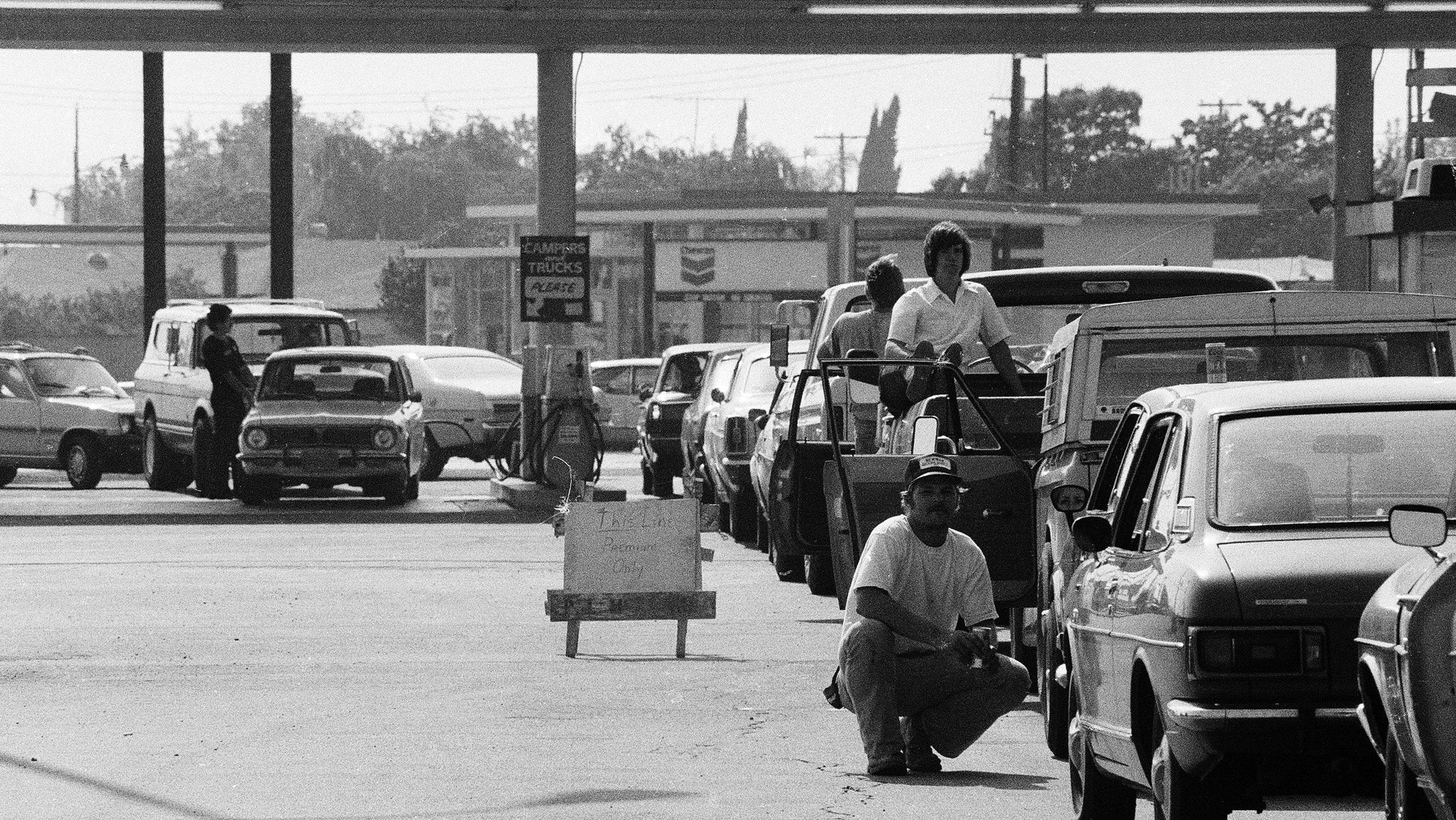

The US has been here before: Between 1979 and 1981, during the Iran-Iraq war, the price of imported oil in the US doubled. The price had also spiked a few years before that, when oil-exporting countries in the Middle East cut off deliveries to the US and other nations that were supporting Israel in a war against Egypt. Before those crises, between 35-45% of US oil was imported, and when supplies fell, price spikes and shortages led to hours-long lines at gas stations.

In response, US policymakers implemented a few straightforward fixes—the country’s first vehicle fuel economy standards—that had the effect of quickly reducing US oil consumption, which fell nearly 20% in the five years after 1979. In addition, the US lowered speed limits, lifted gasoline price caps, burned more coal in power plants, and increased public spending on renewable energy research.

The experience is proof that rapid change is possible in the energy system when national security demands it, says Christopher Knittel, director of Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at MIT. That’s good news for Europe, which is scrambling for alternatives to Russian fossil fuels.

Europe should pivot more quickly from fossil fuels

History offers another lesson, too: Demand rebounds quickly once conservation mandates relax. As geopolitical tensions eased in the 1970s, US public support evaporated for more ambitious fuel standards, or higher gas taxes (pdf)—which would have incentivized fuel conservation and innovation in alternative technologies, but kept gas prices elevated.

“Because the oil shocks were so transitory, the US took its foot off the gas pedal” on energy transition policies, Knittel says, adding that Europe shouldn’t make the same mistake. No matter what the coming weeks bring in Ukraine, the region should seize the moment to accelerate its clean energy transition—even if it means keeping oil and gas prices elevated for a while.

That means maintaining political support for carbon markets (Europe has the world’s highest prices for emissions credits), and sticking with plans to build more renewable energy and tax fossil fuel companies even after the Ukraine crisis dies down. Doing so would insulate Europe from future Russian political leverage, and spur a leap ahead toward decarbonization goals—a concern that wasn’t yet on the table in the 1980s. Carbon trading and fossil fuel taxes can also form pools of government revenue from which to support energy bill subsidies and other safety nets for low-income households, which suffer the most from high prices.

Given the gravity of the invasion, and the urgency of climate change, Europe’s efforts are likely to show more staying power than the US’s did 40 years ago, Knittel says. “It’s not going to be painless or instantaneous,” he says, “but it will be harder to forget the war than it was to forget high oil prices.”