A uranium price collapse has made mining companies radioactive to investors

Here’s the latest sign that uranium-mining doesn’t pay: Paladin Energy, an Australian uranium mining group, announced today that it was ceasing production (pdf) at a key mine in Malawi. The move will take 3.3 million pounds of uranium per year off the market.

Here’s the latest sign that uranium-mining doesn’t pay: Paladin Energy, an Australian uranium mining group, announced today that it was ceasing production (pdf) at a key mine in Malawi. The move will take 3.3 million pounds of uranium per year off the market.

Paladin blames the plunge in the market price for the commodity, which has been languishing below $30 per pound, down from a peak of around $140 per pound in 2007:

The firm said it will restart its idled mine, a process that takes nine months, only when uranium prices rise to $70-75 per pound, or nearly triple the going rate.

Paladin is far from alone. As uranium prices have tumbled, others have been feeling the pinch. Indeed, for some 60% of global uranium production, the cost of extraction is higher than the market price for the commodity, the firm says.

In 2012, BHP Billiton put off a $20-billion expansion plan for a mine that sits on the world’s largest known uranium deposit. The prospects for processing more yellowcake at the site still look dim, given depressed prices. Yesterday, the French nuclear group Areva signed a uranium mining deal with the government of Niger, the world’s fourth-largest producer, but immediately put the start of the project on hold until prices improve. “Neither Areva nor Niger are interested in dumping uranium on the market that would not find a buyer,” Areva boss Luc Oursel said.

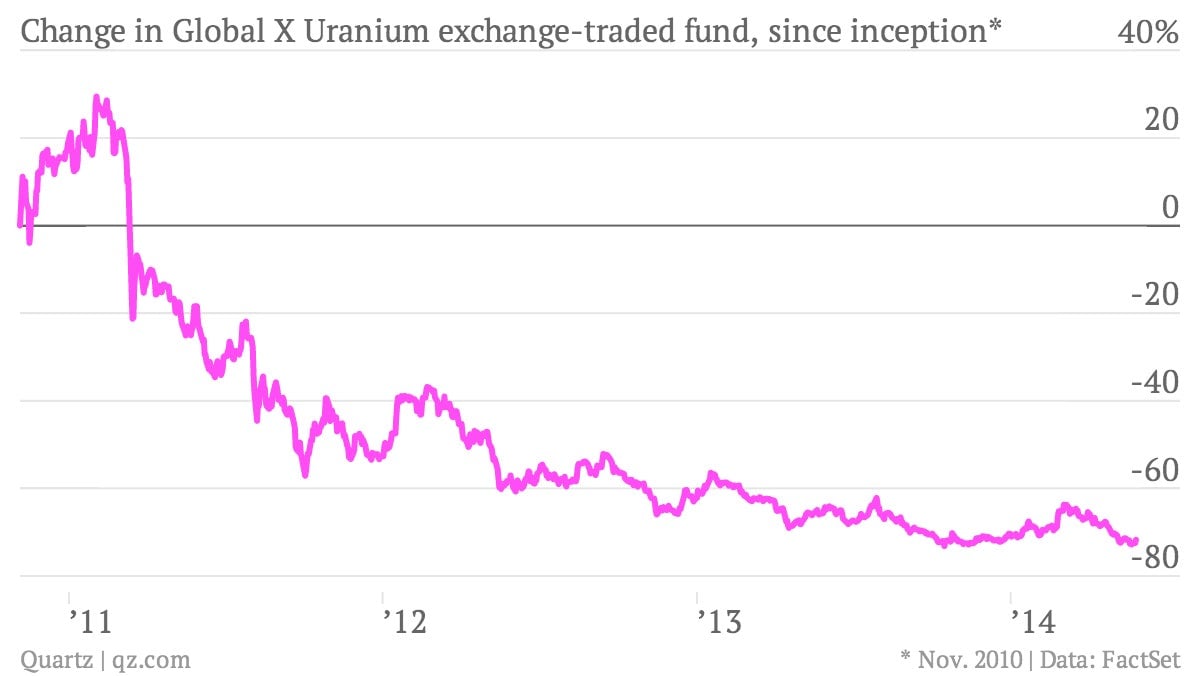

Uranium prices have been hit by a series of setbacks in recent years, from a global financial crisis that put a big dent in nuclear power demand, to a glut of decommissioned weapons-grade uranium, to the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, which led to the shutdown of all that nation’s nuclear power plants and inspired nuclear phase-outs in places such as Germany and Switzerland. Investors in uranium mines have seen their assets plunge in value:

After each setback, mining companies see better days around the corner. But Japanese officials have been fighting stiff opposition to restart the country’s reactors, and ambitious nuclear expansion plans elsewhere in Asia, particularly China, will take years to come online.

Although Paladin reckons that uranium demand will begin to outstrip supply in 2016, it has also been trimming its price outlook—in March it said the price at which it makes sense to restart its mine in Malawi won’t be reached until 2016, instead of next year. And so the half-life of the uranium bust continues to last longer than many expected, making market conditions inhospitable for mining companies, as well as the long-suffering investors that placed their faith in them.