By the numbers, the rise of Europe’s far-right looks like a trend, not a blip

Traditional centrist political parties were shaken by the euroskeptic “earthquake” that saw far-right upstarts capture a big share of the vote for the European Parliament last weekend. Nearly a third of incoming deputies in the chamber will be anti-EU “malcontents,” according to think tank Open Europe.

Traditional centrist political parties were shaken by the euroskeptic “earthquake” that saw far-right upstarts capture a big share of the vote for the European Parliament last weekend. Nearly a third of incoming deputies in the chamber will be anti-EU “malcontents,” according to think tank Open Europe.

Typically, vanquished pro-EU political leaders have rationalized the success of the far-right in European elections as a one-off protest vote, flattered by low turnout. For all of the damage that euroskeptics in the pan-European parliament can do to deeper EU integration, it takes legislative power in national capitals to achieve their ultimate goal: getting their countries out of the EU altogether. And while voters may cast their lot with fringe parties for the obscure, distant parliament based in Brussels, they will hew closer to the center in elections for their national parliaments. Or so the theory goes.

But what if that theory is wrong, and far-right votes for the European Parliament are a “gateway drug” to supporting the same upstart parties in the next national elections?

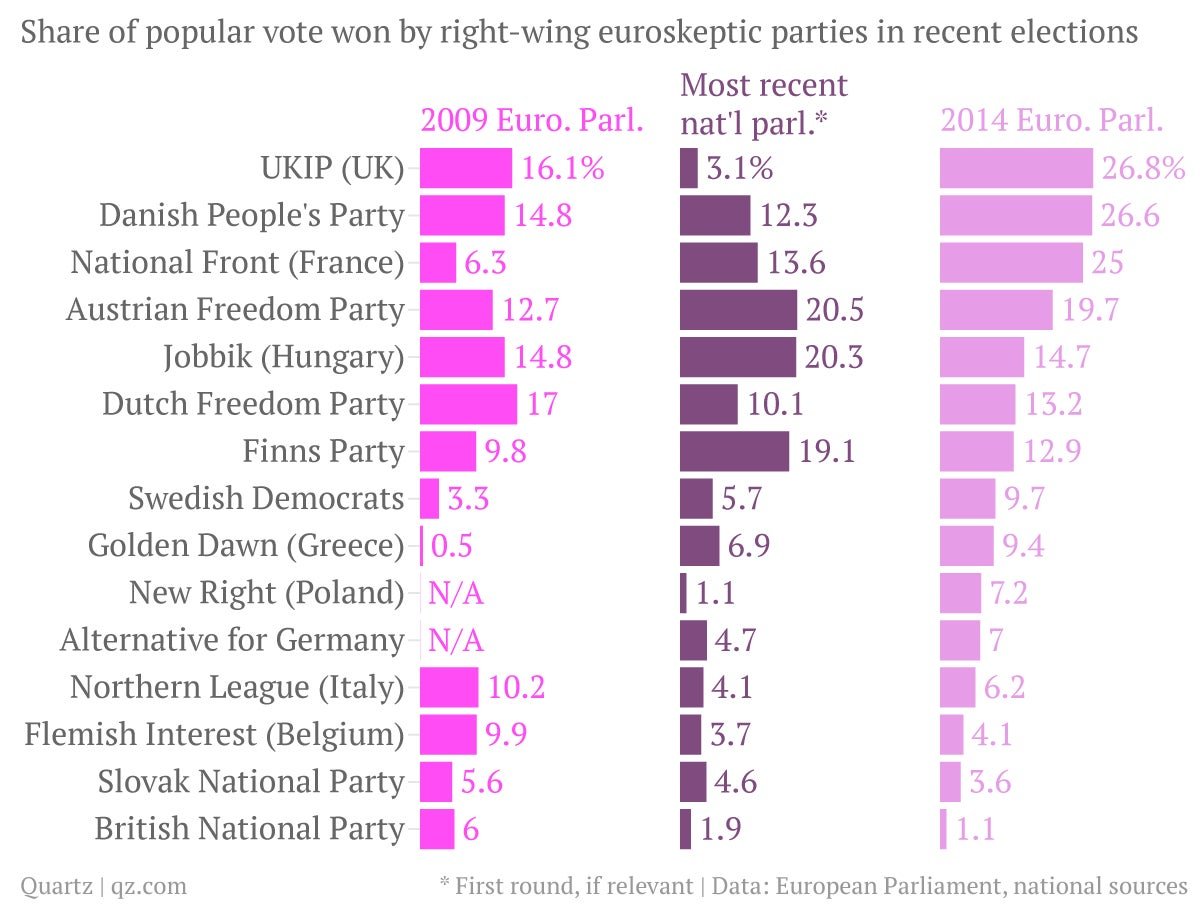

Incumbent parties like to cite the UK Independence Party (UKIP) as evidence that this won’t happen. UKIP was the biggest right-wing winner in the latest European Parliament election, with nearly 27% of the vote, and did pretty well in 2009 too. But it has yet to win a seat in the British parliament, garnering only 3% of votes in the 2010 general election sandwiched between the European polls.

Compared with its ideological peers, however, UKIP looks like an outlier:

Granted, right-wing parties in Belgium, Denmark, Italy, and the Netherlands also haven’t done as well at home as they have in Brussels, but the pattern is much less pronounced than for UKIP. And although the British National Party and Slovak National Party have seen their popularity steadily erode in successive elections, coming away with no seats in the latest pan-European poll, they were never major players to begin with.

Other far-right parties, meanwhile, have shown growing strength in successive European and national elections, including France’s National Front, the Swedish Democrats, and the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn in Greece. Far-right populist parties in Austria, Hungary, and Finland actually did better in their most recent national elections than in the weekend’s European poll. It remains to be seen whether newish parties like the Alternative for Germany and Poland’s New Right will continue the momentum from their inaugural national and European polls.

“The temptation in Brussels and national capitals will be to view this as the peak of anti-EU sentiment as the eurozone crisis calms down and the economy improves,” says Open Europe director Mats Persson. “This would be a huge gamble.”