Why it was so easy for Korea to overtake Japan in the pop culture wars

If you dismiss Gangnam Style’s popularity as just a freak meme (714 million hits as of this posting), you do so at your own peril. As World Bank President Jim Yong Kim pointed out in a recent interview, Korean rapper Psy is a late-appearing symptom of South Korea’s ambition to be the world’s pop culture factory. South Korean soap operas, music, and junk food already dominate the Asian cultural scene, and its westward expansion is a foregone conclusion. Case in point: the hit TV show Glee will be performing Gangnam Style on an episode to air in November.

If you dismiss Gangnam Style’s popularity as just a freak meme (714 million hits as of this posting), you do so at your own peril. As World Bank President Jim Yong Kim pointed out in a recent interview, Korean rapper Psy is a late-appearing symptom of South Korea’s ambition to be the world’s pop culture factory. South Korean soap operas, music, and junk food already dominate the Asian cultural scene, and its westward expansion is a foregone conclusion. Case in point: the hit TV show Glee will be performing Gangnam Style on an episode to air in November.

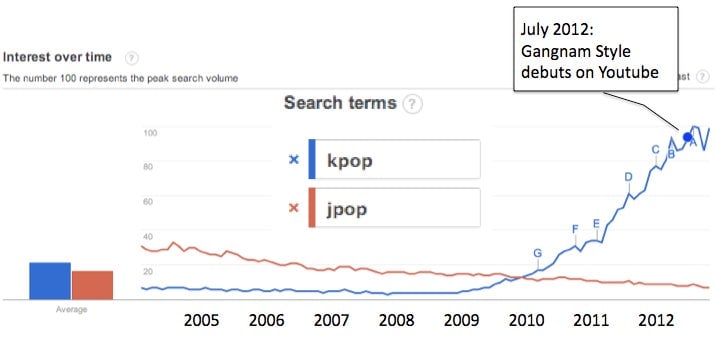

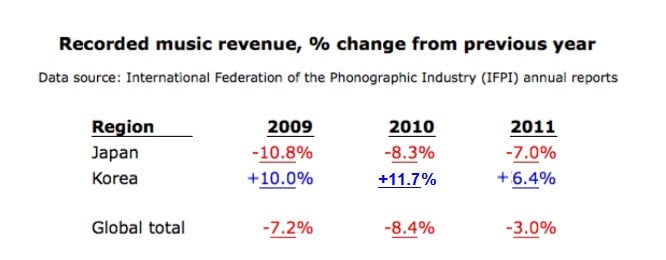

Once, Japanese movies, video games, and pop music were all the rage. But now, the epicenter of Asian pop culture has moved 700 miles (1000km) westward, from Japan to Korea. And no, it didn’t start with Gangnam Style. Check out this Google Trends chart, which shows the number of Google user searches for the term “K-pop” versus searches for “J-pop”, from 2004 to the present. K-pop searches began to skyrocket fully two years before Gangnam Style’s July 2012 debut: As for music revenue, South Korea’s upswing goes against the negative trends in Japan and the world as a whole:

Furthermore, from 2010 to 2011, South Korea’s videogame exports increased 37,7%, according to Korea.net, and foreign rights for Korean films increased 14%, according to the Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. Not too shabby, considering that South Korea’s per capita GDP as of 2011 ($22,424) is less than half that of Japan ($45,870).

Japan’s pop-culture dominance is hurting, and not just in music. Sanrio, the Japanese company that invented Hello Kitty, had a sales slump from 1999 to 2010 and is trying to bring in new characters to reduce its reliance on Hello Kitty. The Japanese film industry suffered greatly from the decline of Anime. As for the once dominant videogaming industry–well, it’s not a good sign when one of Japan’s top game designers (Keiji Inafune, creator of Mega Man) announces, “Our game industry is finished.”

Why is Japan’s cultural influence waning? One might argue it was always on shaky ground to begin with. As early as 1891, Oscar Wilde wrote in The Decay of Lying, “The whole of Japan is a pure invention…. There is no such country, there are no such people.” In other words, the West had exoticized Japan to the point that it ceased to be a real place. Thus, although cultural trends infiltrated the West, it was to a limited extent and in erratic spurts: Karate, Manga, Anime, Hello Kitty.

South Korea is ready to rush in where Japan now fears to tread. There are a number of reasons why South Korea’s ambitions to be the world’s pop culture factory are not totally crazy.

Reason 1: These days, Japan makes stuff mostly for Japan.

Japanese pop culture, like the Japanese archipelago itself, is too isolated from the rest of the world to have remained a sustainable global influence. This is evidenced by the neologism “Japan Galapagos Syndrome,” which compares Japan to the South American island that has its own species and ecology. In 2010, Japanese electronics company Sharp launched a tablet in Japan that was initially sold nowhere else in the world, appropriately called the Galapagos tablet. Similarly, many of Japan’s videogames are for the Japanese market only.

Some say the problem is Japan’s reluctance to learn English and its negative population growth. Others point out that Japan, whose population is 127.8 million, is a huge enough consumer market as it is, and Japanese retailers don’t feel the need to take the huge risk of launching an overseas marketing campaign. (South Korea’s population is less than half that, at 49.8 million).

Ironic, given that it was Korea, not Japan, that was once dubbed “the Hermit Kingdom” by frustrated Western conquistadors in days of yore.

Reason 2: Korean culture is puritanical–and for global spread, that’s a good thing

Despite what you see in Korean movies, sexual repression in everyday South Korea is enforced to an annoying degree. A female Korean-American friend of mind recalls not being allowed to attend slumber parties as a child, because, “You don’t sleep at another person’s house until you are married.” When I’m with my parents, who live in Seoul, I am still expected to walk out of the room if we’re watching a movie with a sex scene, even though I’ve been an adult for quite a long time. They still won’t let me take taxis at night because they’re worried I’ll be kidnapped.

Weirdly, a lot of Western parents can relate to, and even envy, such concerns. If a somewhat conventional culture like the US is going to accept a foreign pop trend, it has to have palatable morals, and overprotectiveness is an appealing one.

Japan is a different story. It, too, is sexually repressed, but it’s not puritanical. Take the J-pop band AKB48 (so named because the band has 48 members). They frequently wear school uniforms while performing, and their songs have lyrics like “My school uniform is getting in the way.” A song like that would be banned in Korea.

In Korea, by contrast, schoolgirl uniforms are only worn… for school. And they have much longer skirts than do their Japanese counterparts.

Japanese girl idols are expected to publish photobooks, consisting of pin-up style pictures. The Guardian wrote that such books “will invariably feature a selection of bikini shots shot on beaches in Hawaii…Sales of photobooks are so brisk that they have their own charts.”

Meanwhile, Korean culture protects childhood innocence at any price. Which means that even if the K-pop idols are of age, they can’t appear in a spread that would be inappropriate for their child fans. Patrick St. Michel noted in our sister publication the Atlantic that K-pop bands “aren’t glimmering examples of feminism, but at least they look and act like grown women.” An example of a somewhat grown-up K-pop girl band is the nine-member Girls’ Generation, recently featured in The New Yorker.

Here’s a video of Girls’ Generation singing their hit, “The Boys.” This is pretty much as naughty as it gets:

Part of South Korea’s puritanism has to do with having a large Christian population (26.3%, as opposed to Japan’s 2%). But most of it predates the arrival of Christian missionaries by many centuries. The preservation of childhood innocence is rooted in Confucianism, a rigid system of social order that dominated every aspect of public and private life.

Confucianism began in China around the fifth century BC and migrated to Korea. By the 14th century, it had became Korea’s system of governance, and this led to a lot of weird stuff, including male primogeniture, filial piety, and the use of really hard exams for determining one’s entire life course.

Part of the Confucian way was extreme sexual separation.“Boys and girls must not share a seat after age seven,” was the dictum, and even as adults, aristocratic men and women in old Korea lived in separate compounds.

Japan, meanwhile, did adopt some Confucian elements, but never as strongly as in Korea; today, 83.9% of Japanese are followers of Shinto, an indigenous Japanese religion.

And for what it’s worth, the K-pop boy acts (Rain, Super Junior, Big Bang) were popular exports before the girl bands ever were. I hope this means that the popularity of K-pop has to do with general appeal and not just some submissive fantasy of Asian women.

Here’s a particularly awesome male K-pop video, “Keep Your Head Down,” by TVXQ:

Reason 3: Because Americans are seen as the heroes of the Korean War, South Korea has been closely influenced by US pop culture. Japan, less so.

Despite some grumbling, South Korea still sees the US as its protectors during the Korean War (1950-1953). The US continues to maintain an enormous military presence in South Korea–some 30,000 –and this has had a powerful effect on South Korean music tastes. Several generations of South Koreans grew up hearing American pop on American Forces Network television and radio, and US soldiers’ tastes created the demand for American music to be sold in shops and played in night clubs. Perhaps this is why the K-pop sound is much more US-influenced than J-pop is, particularly with the K-pop’s predilection for R and B, hip-hop, and rap.

The K-pop sound, therefore, has a familiar ring to a worldwide audience raised on American pop.

Reason 4: K-pop has already conquered Europe.

For some reason, 15,000 people gathered at Rome’s Piazza del Popolo on Nov. 10 for a flash mob Gangnam Style dance. And at the MTV Italy awards in May, K-pop boy band Big Bang won the “Best Fan” award, whatever that is.

Pucca, the oddly-drawn South Korean cartoon, achieved popularity in Europe years before Walt Disney bought the production rights and brought her to the US.

Europeans, and particularly the French, love Korean pop culture with a frenzy. Part of this may be because the K-pop sound has–in addition to the aforementioned American influences–elements of big band Europop, and is redolant of old French Eurovision acts like France Gall.

K-pop bands are so popular in France that in April 2011, tickets for a multi-band K-pop concert sold out in 15 minutes, and days later, thousands of French people protested in front of the Louvre to demand a repeat performance. The story made the front page of both Le Monde and Le Figaro.

That said, Koreaphilia in France began not with music, but with film. The French have always been easily open to multiculturalism when it came to cinema, and they embraced the raw emotion of Korean “revenge” movies like Palme d’Or winner Oldboy—whose plot probably seemed familiar to the French, as it was based loosely on Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo.

These days, I know a number of Parisian filmgoers who have a standing policy of seeing every new Korean movie that comes out, just as they used to see every Woody Allen before he started making crap.

Reason 5: The South Korean recording industry is run like Hyundai and Samsung.

The Korean pop industry is run like Korea’s chaebols (giant Korean conglomerates). Hyundai and Samsung are much closer models to Korean music companies than are EMI or Columbia records. There are only three big Korean recording companies (SM Entertainment, JYP Entertainment, and YG entertainment), and they own all the distribution channels and every point of entry. Independent talent agencies are insignificant; record labels do all their own recruiting.

They don’t find the star; they make the star. Tiffany, a member of Girls’ Entertainment, was discovered in a California mall and trained for three years and seven months before ever appearing in public.

Like the Monkees or Menudo, the bands exist before the members are picked. There is virtually no room for a Bob Dylan type to start out strumming in coffeeshops and rise out of obscurity.

No US record label would invest the resources to train performers for that many years. A lot can happen to a teenager between the ages of 14 to 18: they could go to another label or turn to drugs. The Korean recording contract, by contrast, is airtight. The performers in K-pop bands are usually not even allowed to date. At all.

The structure of the J-pop industry is superficially similar to that of Korea, but it’s always had one major difference: Japanese pop music is much more experimental and often avant-garde (think of the Plastic Ono Band). They even went through a rockabilly stage in the 1960s (“rokabiri”) and play around with cross-cultural hybrid sounds. South Korean tastes, meanwhile, are factory-made and conventional: the country has never had a hair band.

Reason 6: The Japanese are nutty for Korean pop culture, and have pretty much voluntarily ceded the tastemaker role to South Korea.

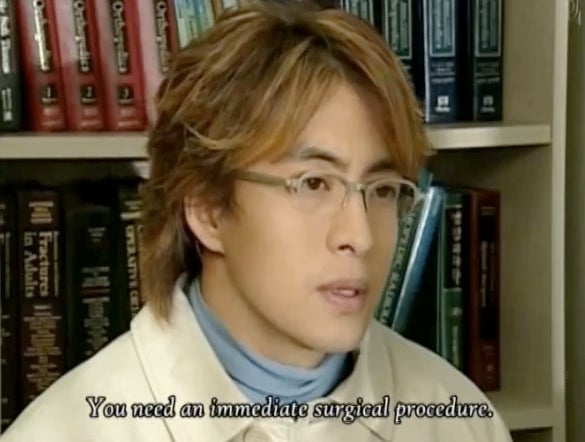

Korean fever first hit Japan in 2003, the year that the runaway hit South Korean soap opera Winter Sonata premiered on Japanese TV. The plot centers around an architect recovering from amnesia and re-discovering his childhood sweetheart. Its male star, the unassuming, bespectacled Bae Yong-joon, was subsequently credited with the $2.3 billion rise in trade between Japan and South Korea between 2003 and 2004, including tourist revenue arising from tours to the fictitious character’s hometown.

In August 2004, then-Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi said during elections for the upper house of Parliament, ”I will make great efforts so that I will be as popular as Yon-sama.” (Bae’s honorific nickname in Japan).

An important reason behind K-pop’s success, even in Japan’s home turf, is that Korean music labels embrace YouTube as a way of popularizing their songs. By contrast, in the words of a Japan Today article, ”Unlike their Korean pop equivalents, most Japanese labels are allergic to promoting their artists’ work abroad.” South Korea, meanwhile, has seized upon music marketing over the Internet (aided by the world’s fastest broadband.) Its influence is so great that Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei recently used K-pop to get the the world’s attention by doing his own Gangnam Style parody. The Chinese government censored it. Such is the power of K-pop.