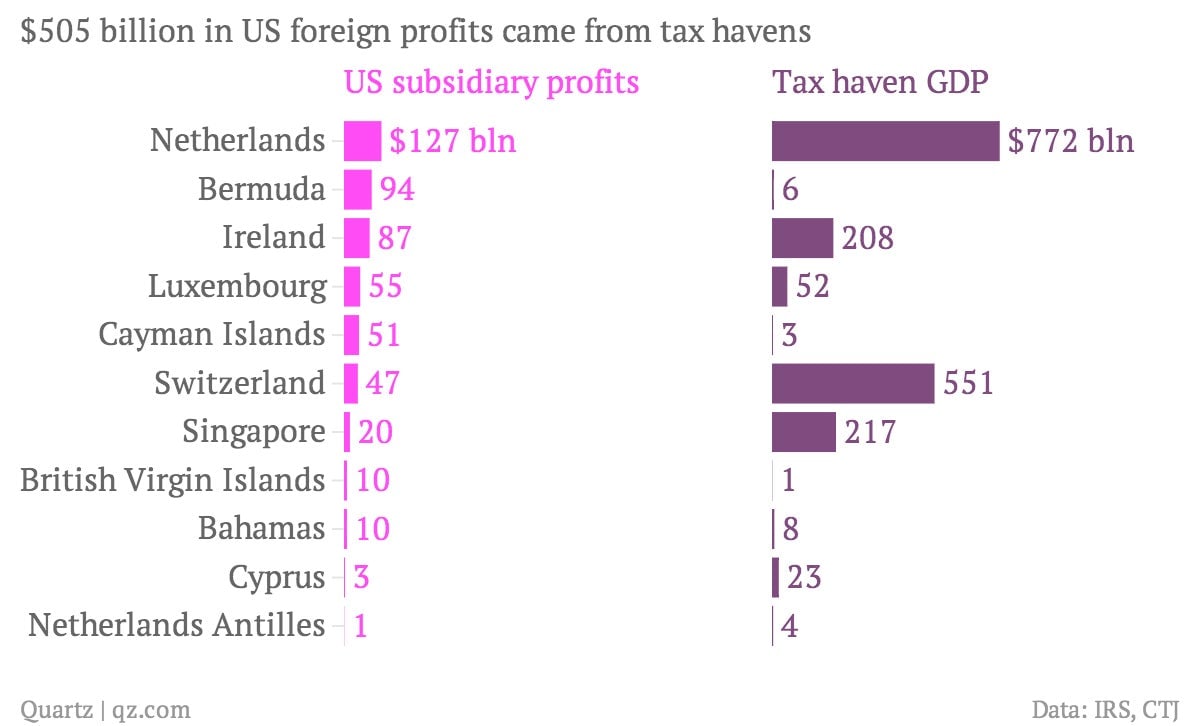

Why US companies can earn $51 billion in the Cayman Islands even though its GDP is only $3 billion

The foreign subsidiaries of US corporations made $94 billion in Bermuda in 2010, the latest year we have data for. That’s incredible work, since only $6 billion of goods and services were produced on the island that year. What does that tell us? It tells us that something fishy is going on.

The foreign subsidiaries of US corporations made $94 billion in Bermuda in 2010, the latest year we have data for. That’s incredible work, since only $6 billion of goods and services were produced on the island that year. What does that tell us? It tells us that something fishy is going on.

This data comes from the Internal Revenue Service and an analysis performed by the NGO Center for Tax Justice. In 2010, US companies reported that their foreign subsidiaries earned $424 billion in non-tax-haven countries—and $505 billion in the 12 countries that are out-and-out tax havens, or go out of their way to make them easy to access:

Did the profits of US subsidiaries in the Netherlands add up to the equivalent of 16% of Netherland’s gross domestic product? Probably not. Nor is the $87 billion in US companies’ profit in Ireland—equivalent to 40 percent of its GDP—particularly credible. What we’re looking at is the result of companies taking advantage of loopholes in US tax law to shift profits from other foreign markets (and even the US) into offshore subsidiaries that are protected from US taxes.

Robert Pozen, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, recently offered two examples of how this works:

[An] American tech company could establish a shell corporation in Bermuda to make a large loan to its computer service subsidiary in Germany. The interest payments made on that loan would be tax deductible in Germany, which has a corporate tax rate above 20%. But the interest payments received on that loan would be taxable only in Bermuda, which has a zero corporate tax rate.

Alternatively, an American drug company could license patents from its Bermuda subsidiary to its German subsidiary. The licensing fees paid on those patents would be deductible in Germany, which would reduce its taxes there. But the licensing fees received by its Bermuda subsidiary would be subject to no corporate taxes in Bermuda or in the U.S.

While there are myriad ideas to fix US corporate tax law so multinational companies spend less time dodging Uncle Sam and more time doing their actual business, few are expected to move through Congress anytime soon.