China keeps using the wrong tools to fix its economic problems

Chinese economists and officials are sounding alarm bells over the state of the country’s stalling economy.

Chinese economists and officials are sounding alarm bells over the state of the country’s stalling economy.

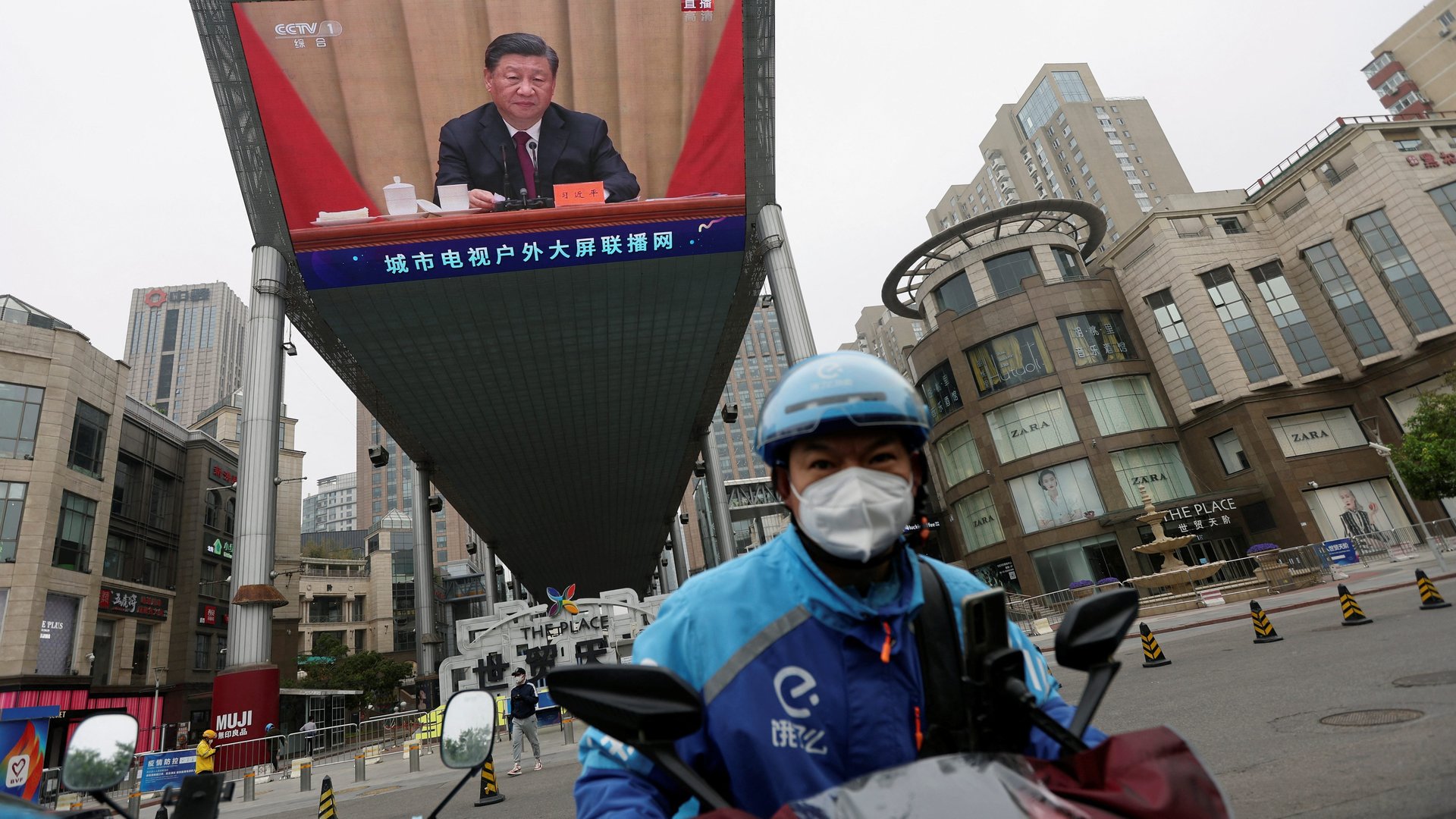

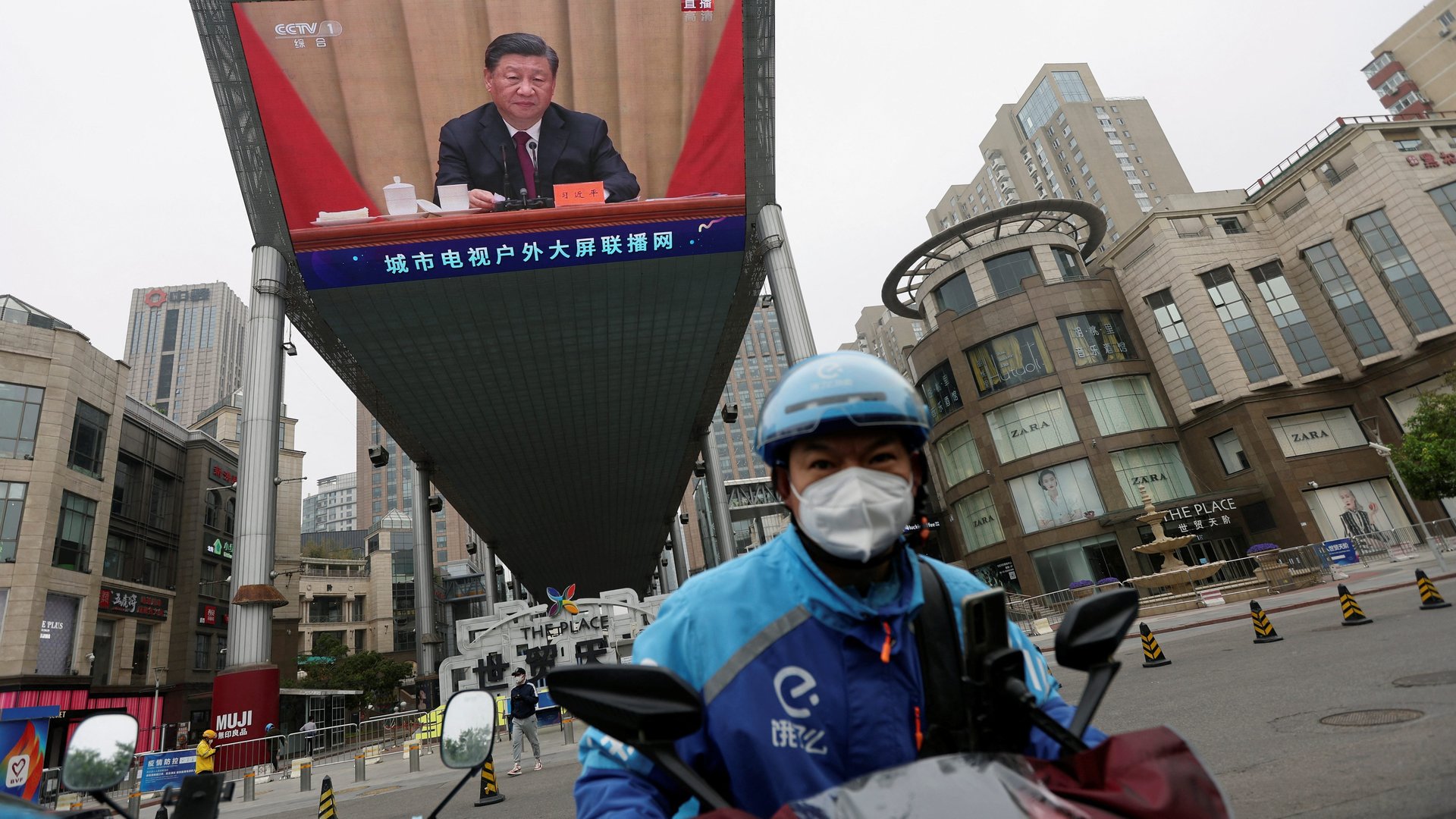

Widespread pandemic lockdowns in key cities and manufacturing regions this year have roiled supply chains and weighed on growth. Businesses are struggling. Data released today paint a dire picture: China’s industrial output and retail sales for April are both down sharply, and unemployment is climbing. Retail contracted by 11.1% from a year earlier, a far deeper plunge than the 6.1% drop forecast by Reuters.

For a government whose legitimacy is heavily dependent on sustained economic growth, this presents a major headache. The question is, will Beijing manage to deploy the right tools to rev up its economy?

“Save the economy at all costs. Hand out money.”

So far, Beijing has rolled out a series of supply-side measures to give the economy a boost. These include massive tax cuts and rebates totaling 2.5 trillion yuan ($400 billion); cutting banks’ reserve requirement ratios; going “all out” on infrastructure investment; and business-friendly policies like fee reductions, financial insurance, and expedited customs clearance procedures.

But one set of economic tools is conspicuously missing: demand-side policies. That is, policies designed to boost demand for goods and services, which in turn drives economic growth.

“Save the economy at all costs. Hand out money,” urged Peking University’s Huang Yiping (link in Chinese), speaking at an economics conference an economics conference this weekend. Huang’s phrase intentionally echoed that of former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, who in 2012 pledged to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

China has long had very weak consumer demand. Among major economies, Chinese households have one of the lowest consumption shares of GDP. This is a function of China’s high-savings model of economic development, which favors government and business investment at the expense of ordinary people’s spending, as Matthew Klein of the Overshoot and Michael Pettis of Peking University explain in their book Trade Wars are Class Wars.

Pandemic lockdowns have weakened household consumption even further. Workers lost income and jobs. People likely saved more in the face of uncertainty. And citizens locked in their apartments for weeks have been unable to spend, except on food—and sometimes not even that.

Prominent Chinese economists have in recent weeks called for measures to boost consumption.

“We have to boost domestic consumption since investment is constrained by the declining expectation on the demand side,” argues Peking University economist Yao Yang. “…I insist on what I have been calling for these two years — giving the people cash to promote consumption.”

Though a handful of Chinese cities have handed out consumption vouchers, there has been no coordinated nationwide campaign.

In fact, premier Li Keqiang all but ruled out cash handouts in a speech late last month. While handouts might be “fair and effective,” he said (link in Chinese), they are unsuited for China because doing so would exacerbate inequality given the uneven development across regions.

Others disagree. Li Xunlei, chief economist at brokerage Zhongtai Securities, says the government should hand out 1,000 yuan ($150) each to China’s population of 1.4 billion. “Consumption vouchers should be issued by the central government … the sooner [they] are issued, the better,” Li said in an interview last month (link in Chinese).

Huang, of Peking University, says the stakes are high. “If we can’t increase consumption, this year’s economic growth will be very challenging,” he said in March (link in Chinese). “…We have to hand out money to the people.”

Demand-side policies could be politically dicey

But a one-off cash handout would only be the first step towards boosting consumer spending.

The more challenging task is to rebalance its entire economy from a reliance on investments and exports to being a consumption-led economy. Beijing has a buzzword for this rebalancing: pursuing “high-quality growth.”

Boosting consumption by increasing the household share of GDP, however, means transferring income from those who’ve long had more of it—governments and businesses—to individual citizens. That’s a politically fraught task, as Pettis argues.

Meanwhile, the flip side of the very low share of GDP retained by Chinese households is the extraordinarily high levels of investment spending, principally on infrastructure and real estate.

But one can invest too much, making it unproductive: think of the “ghost towns” full of empty apartment blocks. Or as Peking University’s Yao put it: “after more than 20 years of high-speed development of infrastructure, local governments can find fewer and fewer good projects.”

Excessively high levels of investment coupled with weak consumer demand is a problem that Japan faced, too. When Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1992, what followed was not a meltdown but decades of stagnation. And there’s another similarity: both Japan and China are aging and shrinking.

Unless China can deploy demand-side policies at scale and radically transform its growth model to prioritize consumption, it may well follow Japan’s path of decades of slow growth.