How Italian soccer stickers turned generations of kids into capitalists

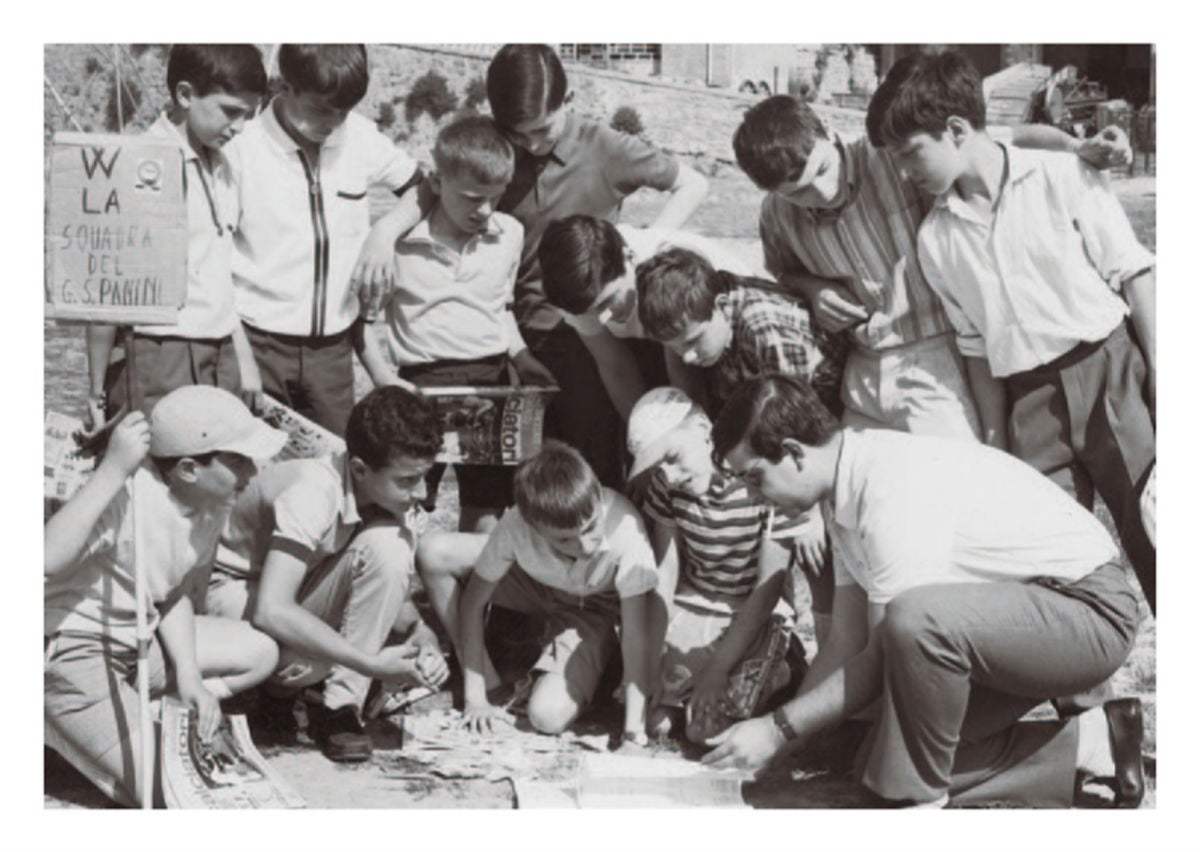

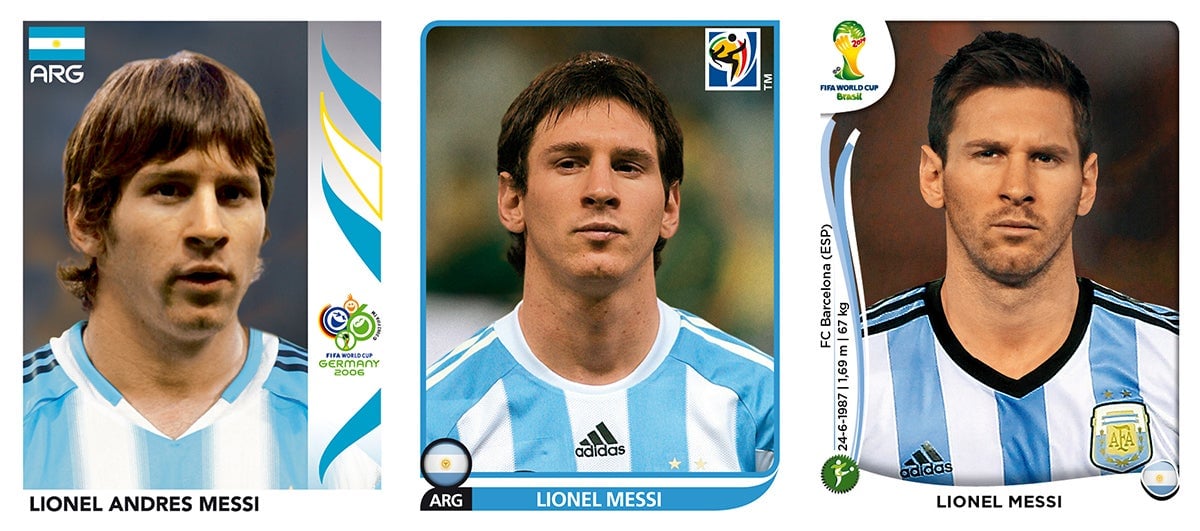

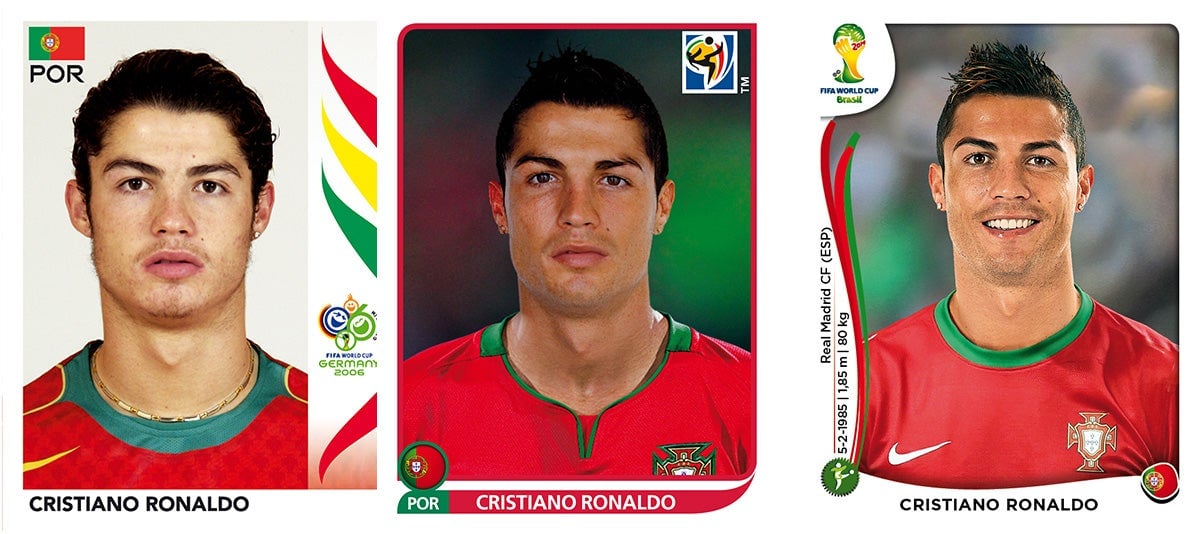

“Ce l’ho, ce l’ho, mi manca“—”Got it, got it, need it”—is the refrain that has introduced Italian kids to the joys of supply and demand for decades. It is the equivalent to the stock market’s “buy, sell,” but it accompanies the exchange of a very different, though similarly precious commodity: Panini stickers, which contain portraits of the football players taking part in the World Cup.

“Ce l’ho, ce l’ho, mi manca“—”Got it, got it, need it”—is the refrain that has introduced Italian kids to the joys of supply and demand for decades. It is the equivalent to the stock market’s “buy, sell,” but it accompanies the exchange of a very different, though similarly precious commodity: Panini stickers, which contain portraits of the football players taking part in the World Cup.

This year, it will take 639 stickers, acquired in randomly sorted packets of five to seven and traded in playgrounds and on street corners around the world, to complete the set.

Collecting Panini stickers is all about anticipation of the World Cup: sticker sales peak in the five months before the Cup and actually decline during the event. Two months after each World Cup is over, no more of its stickers are distributed.

The trade in Panini stickers offers a (usually) gentle introduction to market dynamics. And it’s something kids around the world seem to instinctively get, says Fabrizio Melegari, the publishing director of Panini group’s collectables and sports magazines.When entering a new market, the company never needs to explain to children that the best way to collect a full set is to trade their doubles for those the stickers don’t yet have. “It’s one of the small magics of this product,” he says in Italian. “Stickers have something magic that gets understood immediately.”

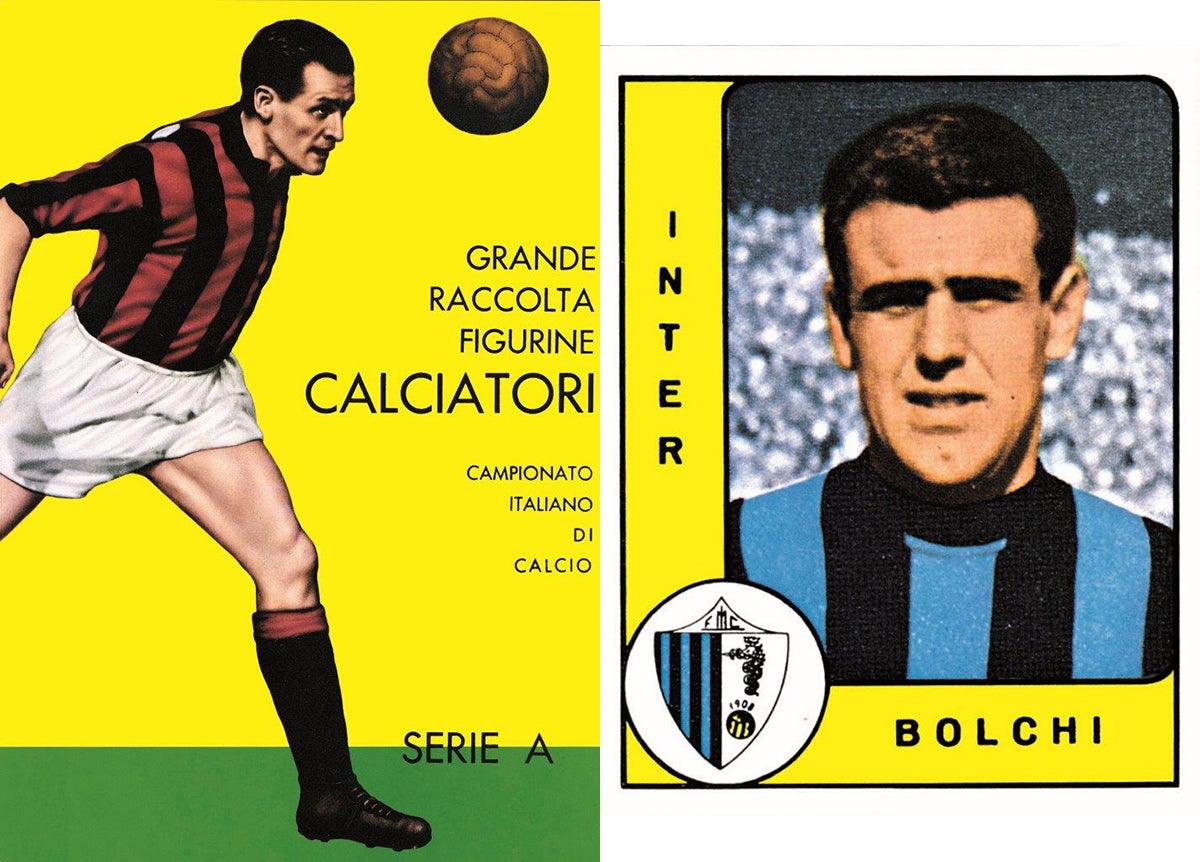

Panini stickers began in 1961 in Modena, Italy—the same town in the middle of the Po Valley that gave birth to Ferrari, Lamborghini, and authentic balsamic vinegar.

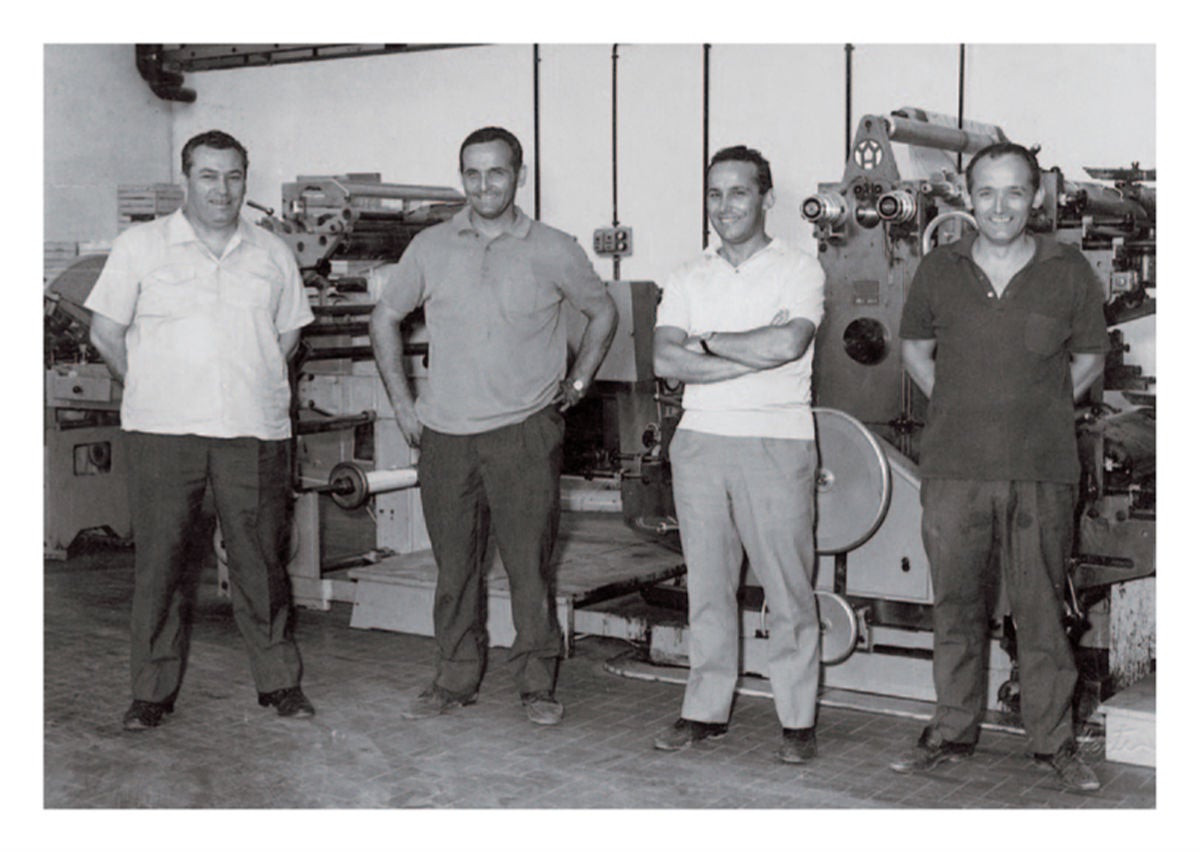

Giuseppe Panini, the oldest of four brothers who had ran the family’s newspaper distribution agency, opened Edizioni Panini in 1961 and printed the first collection of Italian soccer players. He sold 3 million packets containing two stickers each for 10 lire (about 0.7 US cents). The stickers were printed on thick stock paper and had to be glued to the album by the collector.

The next year, Panini sold 15 million packets. The following year it was 29 million—and at that point, all the brothers joined the venture.

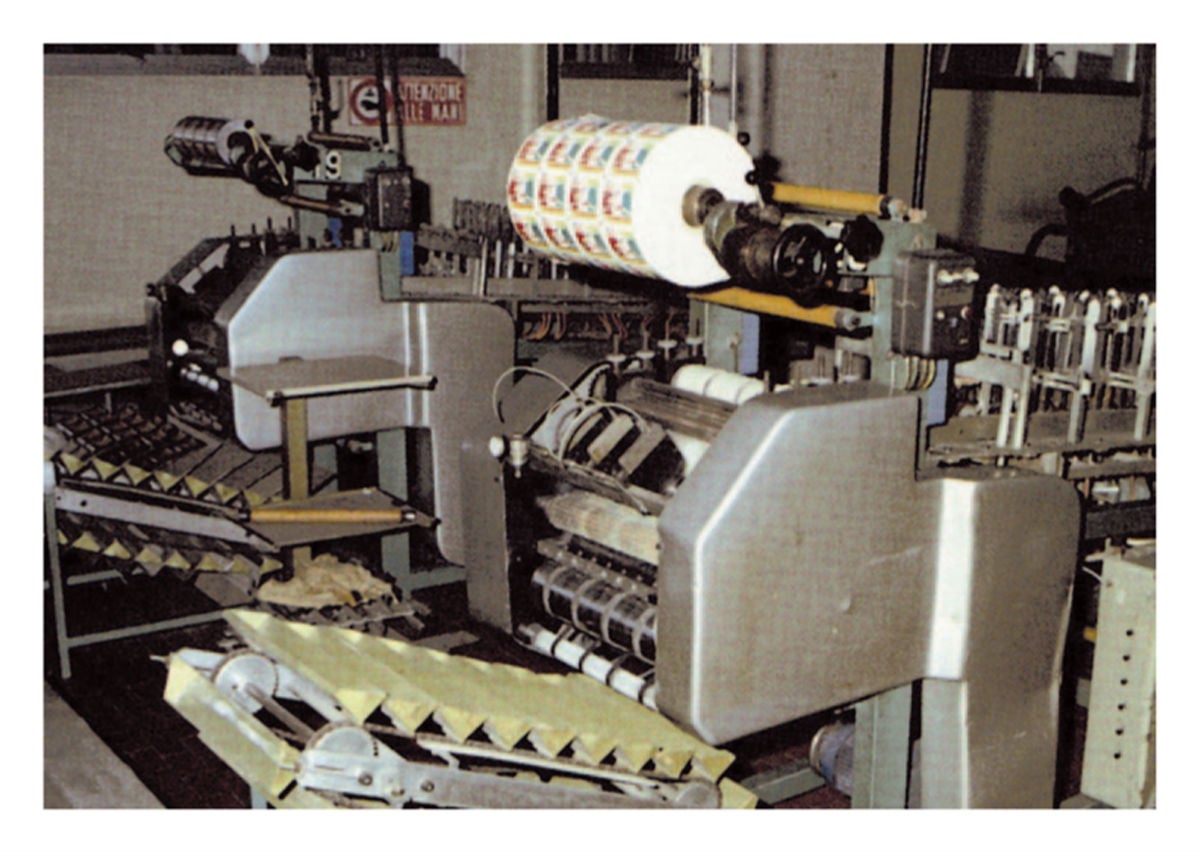

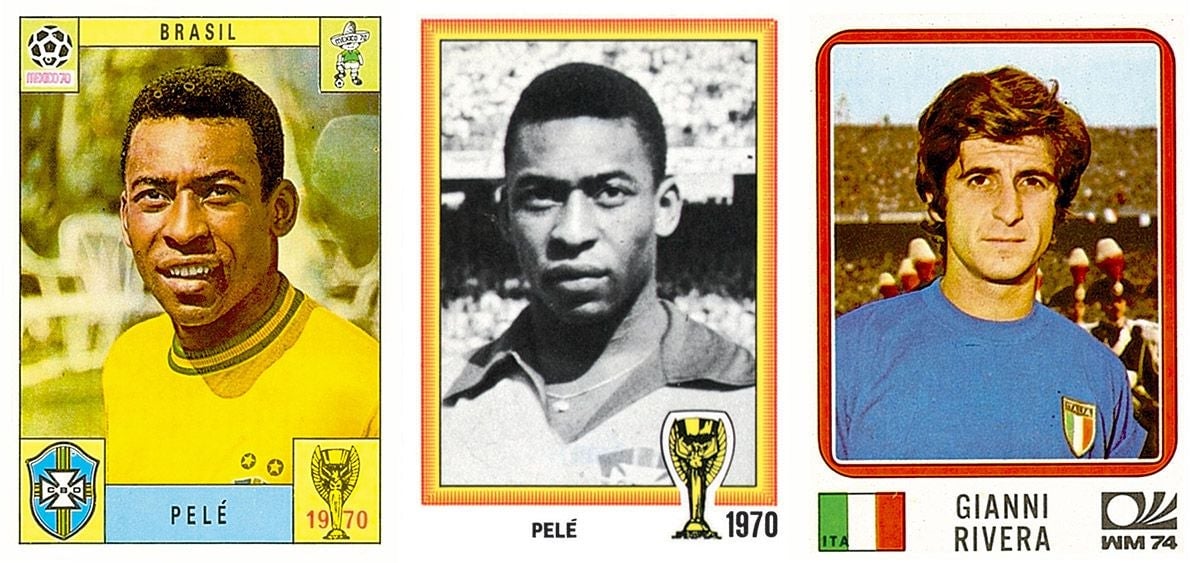

In 1970, Panini expanded internationally. For the World Cup played in Mexico in 1970, two albums were printed: one for Italy and one (with captions in English, French and Spanish) for the rest of the world. By then, triangles of double-sided tape had been attached to the back of the stickers, so glue was no longer needed. A year later, for the Italian collection of 1971-1972, the first self-adhesive stickers were made. They were put together randomly by the so-called “fifimatic,” a machine created by one of the brothers to automate the mixing and packaging of the stickers.

Following the success of Mexico 1970, Panini opened branches in the markets where soccer was most popular: the countries of Western European, followed by Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Turkey.

Currently, Panini has 12 direct branches and a dozen licensing partners producing and distributing albums and stickers in eight languages and 120 countries.

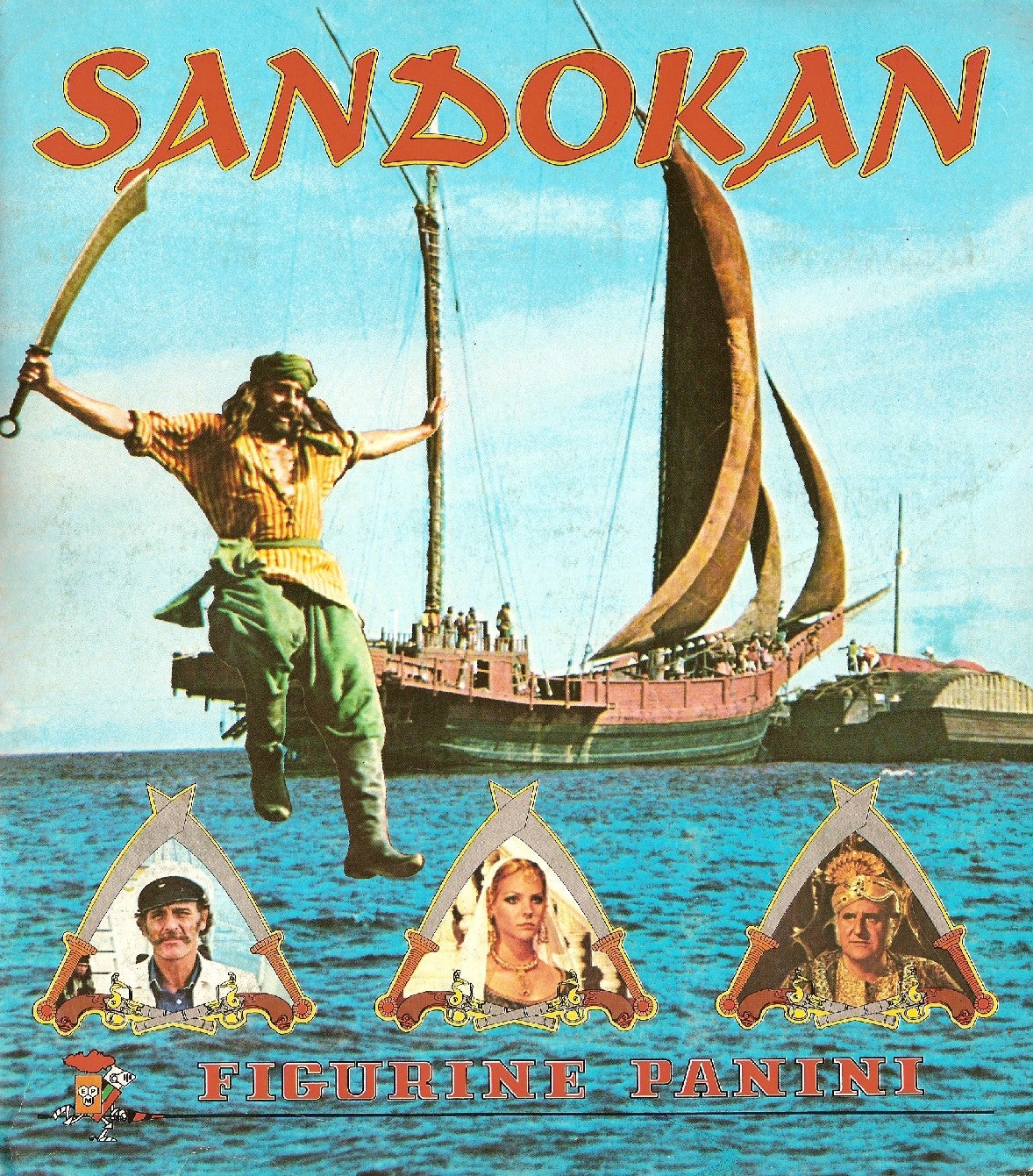

Although the company’s collections are not limited to soccer—they also print sticker albums for cartoons, comics, TV shows, movies—football has always been its best-selling item, with one exception: in Italy in the mid-1970s, a sticker album of images from the TV series Sandokan made a killing among fans of the Indian actor Kabir Bedi and surpassed that year’s Italian football collection.

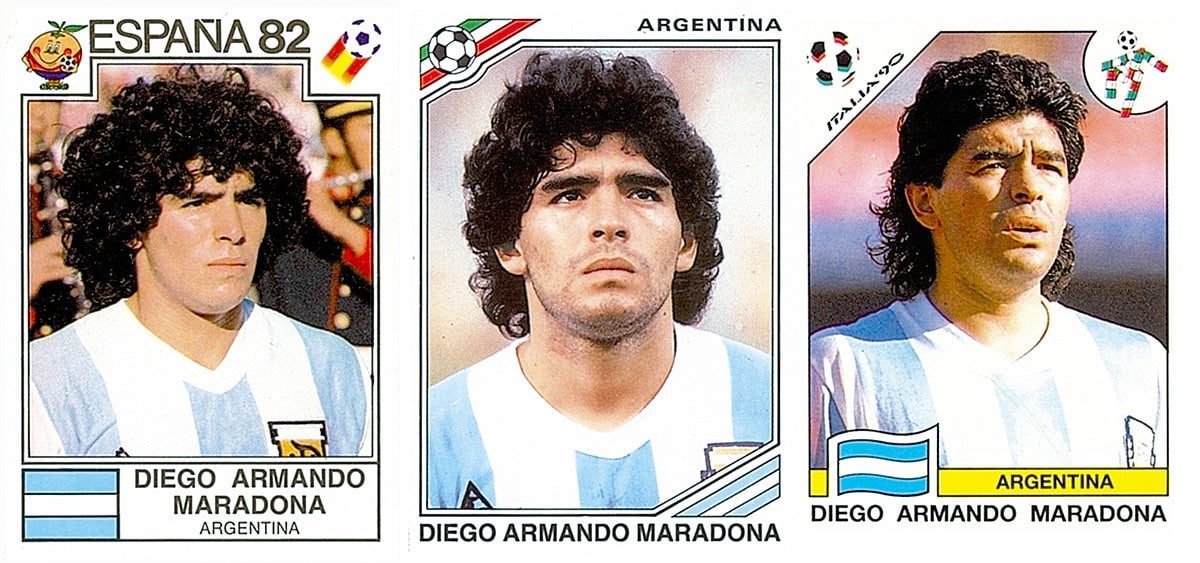

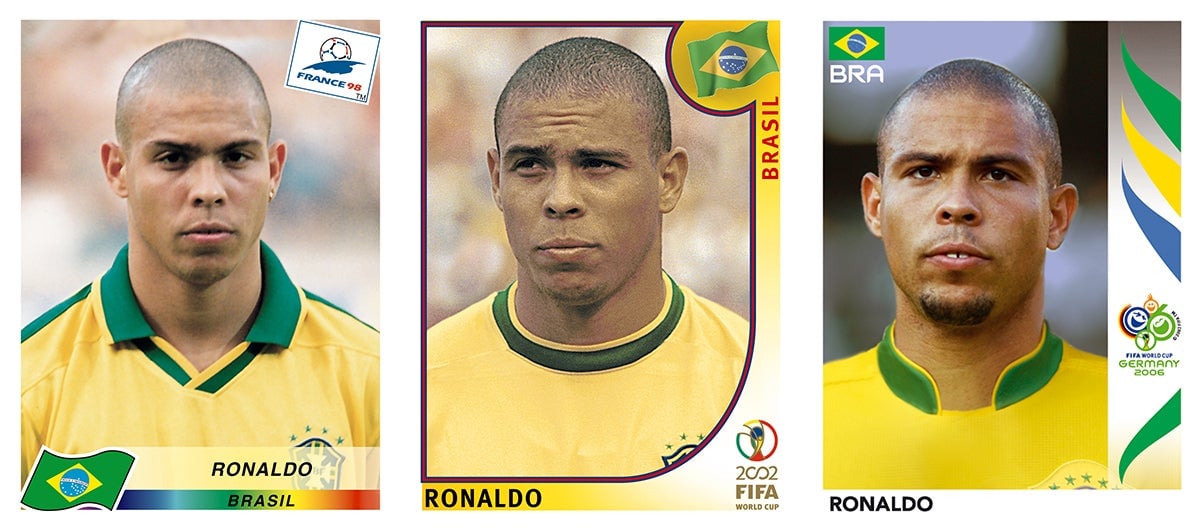

Barring another return of Sandokan, the World Cup is Panini’s most important event: an estimated 15 billion stickers have been printed, collected, and exchanged around the world since 1970. For Panini, as for many of the soccer fans around the world, life goes by four years at a time. ”We use the sports calendar to measure the passing of time,” says Melegari. At ”the very moment the winning team lifts the World Cup,” the company starts preparing for the next competition, he said.

The company has a dedicated team of photographers and journalists—12 in its headquarters and about 35 worldwide—who follow soccer developments in all the countries, trying to guess beforehand which countries will qualify for the World Cup and who the rising stars will be. Since the album goes to print five months before the beginning of the tournament, it’s a high-stakes guessing game to anticipate which star players will be named to each country’s national team.

To explode one widely believed myth: ”Rare” stickers don’t really exist. “All the stickers get printed in equal quantity,” says Melegari. The mixing is automated and random—as confirmed by two Swiss mathematicians, who calculated that it would take 899 packs to complete a set without trading.

Some unscrupulous Panini fans have been known to leave nothing to chance: 300,000 stickers were stolen in Rio in April, and 130,000 disappeared in Sao Paulo the 2010 South Africa World Cup.

After Italy, Panini is most popular in Switzerland, Belgium, Colombia and Mexico. ”The business works across the board,” says Melegari. It’s a product that most people can afford—the album is about $2, each packet of stickers $1 (with variations depending on the country)— and the mix of entertainment, play, and fan culture has created a business that seems to be immune to economic recessions and broader business trends. “In a moment when it looks like print is destined to die,” says Melegari, talking about the undying charm of collecting and trading stickers, ”this allows this product to survive—and how.”