The four charts that make the case for Narendra Modi to liberalize, liberalize, liberalize

By electing Narendra Modi, Indians have changed the shape of their national goal. It is important to note that they have not changed their ultimate objective—to eliminate poverty in a democratically ruled society. They, however, have changed the road they want to take in order to become this society.

By electing Narendra Modi, Indians have changed the shape of their national goal. It is important to note that they have not changed their ultimate objective—to eliminate poverty in a democratically ruled society. They, however, have changed the road they want to take in order to become this society.

For the last 67 years, the path to eliminating poverty was through the redistribution of wealth and income. Now, the country has chosen to eliminate it through higher economic growth. In the original road, the state had to run the economy to prevent further concentrations of wealth and income. In the new road, market liberalization would free India’s remarkable abilities to create wealth—something that has been proven in all the countries where Indians have emigrated to enjoy the advantages of economic freedom.

Up to now, there were three stages in the evolution of Indian economic policy. The introduction of socialism was gradual. Prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru believed the state should get control of the “commanding heights” of the economy by accretion—which is, by having the government investing in those sectors (activities with very large returns to scale, such as electricity, heavy manufacturing, mining, and transportation), which were by law beyond the reach of the private sector.

His daughter Indira Gandhi went a step further. Starting in 1969, she nationalized the large banks, general insurance corporations, oil companies, and coalmines. She also took measures to curb the growth of large domestic and foreign firms, further restricting the areas in which they could invest and imposing an extremely detailed control over their operations. The objective was to restrict the concentration of wealth and economic power.

These policies led to higher government expenditures and as a result of these, in 1991, the government came close to a default of its obligations while the country’s international reserves went down to almost zero. A new administration led by P. V. Narasimha Rao took advantage of the crisis to enact a series of liberalizing reforms that eliminated some of the most radical of the socialist controls introduced by Indira Gandhi.

Thus, India moved toward a moment of decision during the first decade of the new century. No one among the political parties was happy with the status quo. The left wanted to go back to the original Nehru-Gandhi model. Modi’s followers wanted to deepen the reforms started by Rao.

Modi’s decisive victory allows us to ask the question: Were the Indians right in choosing his way, given that their ultimate objective is reducing poverty?

How to tell?

We can use three yardsticks to measure the benefits of each of the alternative policies: first, sheer growth; second, income distribution equalization; and third, poverty reduction. We can use these yardsticks in two dimensions: a comparison of the years of timid liberalizing reforms of the 1990s and 2000s with the initial socialist years, and a comparison of the last three decades with the performance of China, which went all the way in terms of liberalizing reforms.

Growth

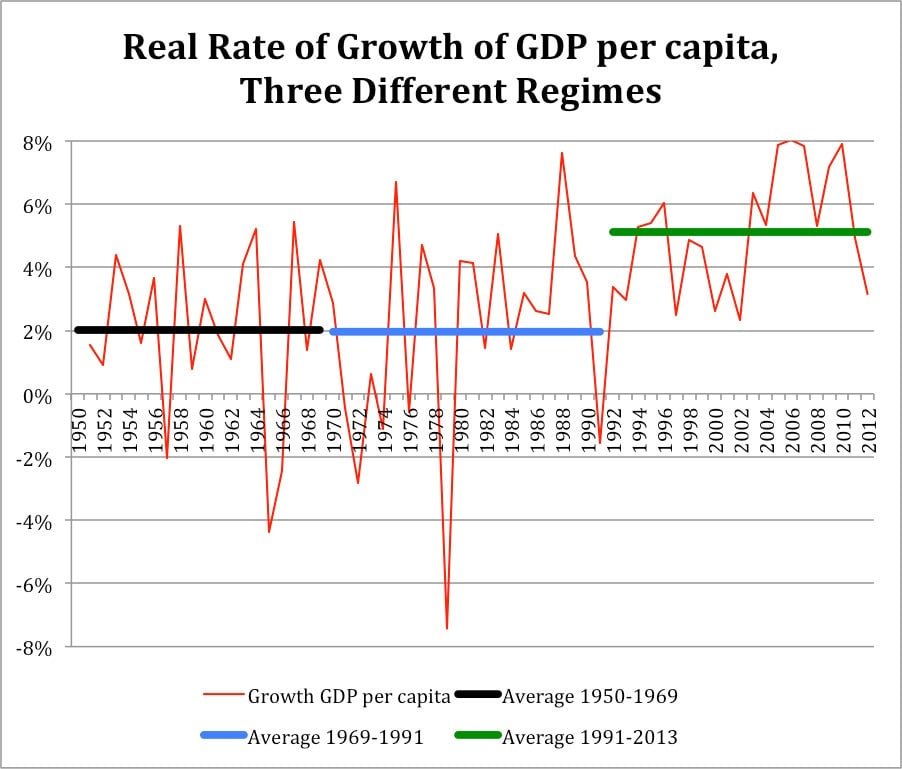

As shown in the next graph, liberalization won hands down in terms of growth. The original socialism of Nehru and the radicalized version of his daughter averaged similar rates of growth during the first four decades after independence. This average, however, doubled during the last two decades, right after the timid liberalizing reforms of 1991. This suggests that liberalization led to higher economic growth.

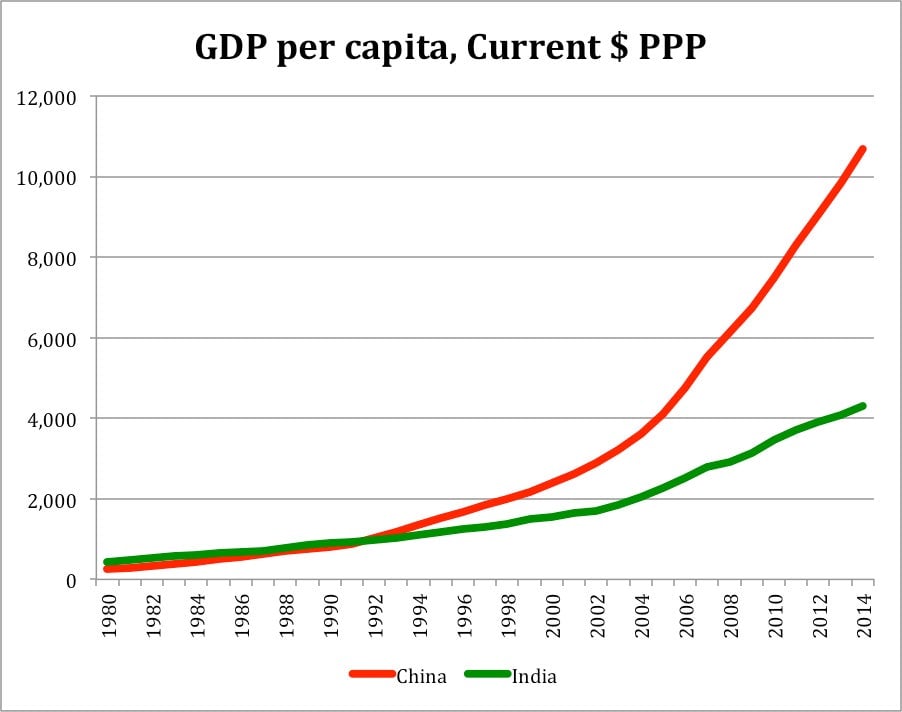

If liberalization leads to higher growth, one could expect that more liberalization should lead to even higher growth. This impression is supported by the next graph. China was not timid in its liberalization and grew much faster than the half-liberated India. In 1980, when China’s liberalization was just starting, its GDP per capita (measured in international dollars with purchasing power parity, PPP) was approximately half that of India. Now it is two and a half times it. No question about why.

Income Distribution

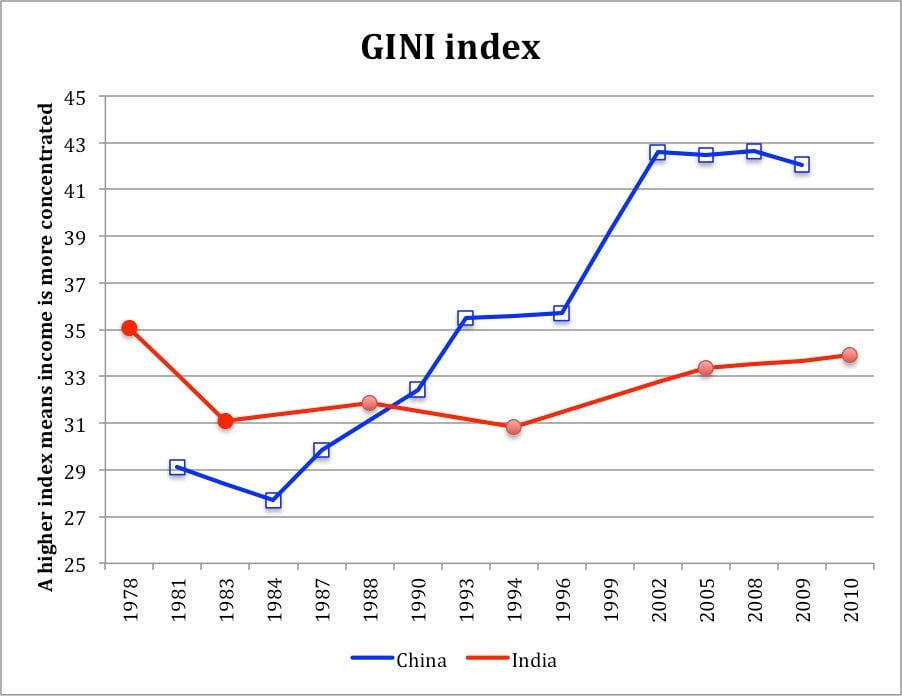

The Indian socialist intellectuals did not discuss this point. They accepted that market-oriented reforms accelerated growth. They, however, said that such reforms also turned the distribution of income more skewed. The next graph suggests that they were right. It shows the GINI index, which measures the degree of equity in the distribution of income by calculating the difference between the actual distribution of income and that of a perfectly equitable society (one in which every citizen would get the same share of the national income). A larger index (a larger difference with the fully equitable distribution) indicates a less equitable distribution of income.

You can see how Indian income distribution became less skewed in the last decade of the Nehru-Gandhi socialist regime. Symmetrically, it became more skewed after the liberalizing reforms of the early 1990s. China, which liberalized all the way, saw its income distribution turning even more skewed than in India—even if China had started with a more equal distribution in the early 1980s. This is telling that both inter-period and international comparisons with China are the same story.

Poverty reduction

Now, however, we can turn toward the reduction of poverty, which is the ultimate objective of both the Congress Party and the supporters of market liberalization.

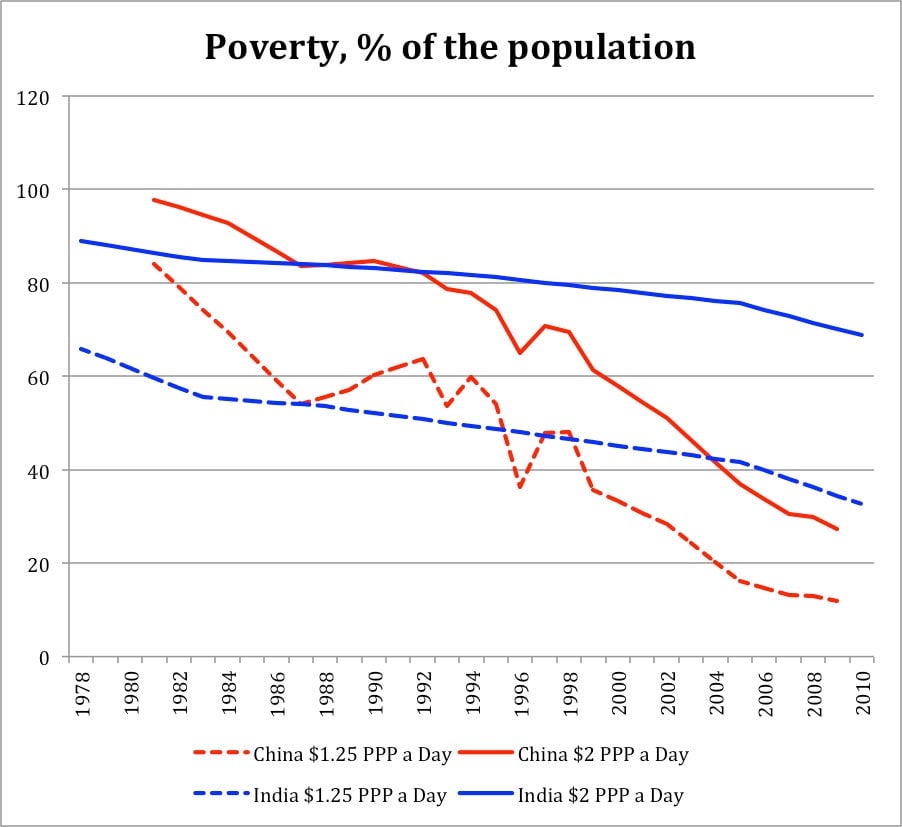

In this respect, if we compare two periods of 16 years, one covering the last part of the fully socialist regime established by Indira Gandhi and slightly modified by others (1978-1994) and the other (1994-2010) covering most of the years after the liberalizing regime initiated by Rao in 1991 and continued by others. We find a tie in terms of the reduction of extreme poverty (those who have an income of $1.25 PPP per day or less, PPP meaning US dollars adjusted by what a dollar buys in each country). This kind of poverty fell by 16.49% of the population in 1978-1994, while it fell by 16.72% of the population in the years since liberalization started in the early 1990s. However, when we compare the change in general poverty (people with an income of $2.50 PPP or less), their number fell by 7.24% of the population during the last years of the Nehru-Gandhi socialism, and by 13% of the population in the liberalization regime. Thus, liberalization wins in terms of general poverty. Decisively.

Now, if we compare these indicators with China, we find that poverty, which in the early 1980s was much higher in China than in India in both the general and the extreme categories, has fallen much faster in China than in India, in such a way that general poverty in India is now 2.5 times that of China, and extreme poverty three times as much. That is, inequality has increased more in China, but poverty has declined much more than in India. If the objective is to reduce poverty, liberalization wins again, decisively. In addition to create a larger economy, it also reduced poverty much faster.

Summary

If Indians persevere under Modi, they are likely to achieve faster their objective of reducing poverty than in the original socialism of the country. Certainly, the distribution of income would become less equal. This, however, is much less important than eliminating poverty, which is what India wants to do and what China has been doing in the last three decades.

Of course, choosing the route is not the same as having traveled it. But that is another story, one that is starting right now.

Follow Quartz India on Twitter @qzindia. We welcome your comments at [email protected].