The FDA holds the key to expanding abortion access

About a month ago in Mexico City, I walked into a pharmacy to see how easy it would be to buy misoprostol, a drug for ulcers that is also used to induce abortions. Very easy, it turned out: All I had to do was ask for the drug and pay 699 Mexican pesos (about $35), no questions asked.

About a month ago in Mexico City, I walked into a pharmacy to see how easy it would be to buy misoprostol, a drug for ulcers that is also used to induce abortions. Very easy, it turned out: All I had to do was ask for the drug and pay 699 Mexican pesos (about $35), no questions asked.

Mexico only recently decriminalized abortion federally, but much like in the US, laws vary by states. Some, such as Mexico City, legalized elective abortion and provide it for free in government hospitals; others limit access, for instance, to pregnancies resulting from rape or incest. But for years, Mexican women seeking an abortion have been able to buy misoprostol, which is sold over-the-counter, irrespective of state abortion laws.

That kind of access to misoprostol would be a game changer in the US now that the US Supreme Court has overturned Roe v Wade and half the country is likely to lose most or all access to abortion. Women in all states, including those that don’t allow any elective abortion, would be able to end their pregnancies without medical assistance.

But for now, misprostol is only available in the US with a doctor’s prescription.

How over-the-counter misoprostol would make an impact

Misoprostol has no severe side effects. The most common ones, which include migraine, nausea, or diarrhea, are tolerable (if unpleasant). For patients with ulcers, there is only one major warning: To not take the drug if pregnant.

But for decades, patients in Mexico, and other parts of the world have been buying misoprostol (both with and without prescriptions) precisely because they are pregnant and don’t wish to be. The World Health Organization (WHO), which recognizes abortion as a human right, has approved pregnancy interruption using the drug, and established clear administration guidelines that don’t require medical supervision.

Typically, medical abortions use a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, which makes the abortion faster and increases the chances of success of misoprostol alone by about 5%. But mifepristone is a newer drug (it was developed in the late 1980s) and it’s still unavailable in many parts of the world. It’s also expensive, which is why, although the WHO also has guideline for combining the two drugs, misoprostol-only regimens are much more common and accessible, particularly in the absence of prescribing doctors.

Misoprostol is about as effective used alone as in combination with mifepristone, especially between the 7th and 12th week. When the fetus is more developed, medical abortions can take longer and subject the woman to protracted contractions, which is why doctors prefer surgical abortions past the third month. All US states where abortion is legal offer medical abortions before the 12th gestational week, and many do so via telehealth, too.(Similarly, states banning abortion don’t allow it via medication either.)

If misoprostol were available over-the-counter, access to abortion would dramatically expand. More than half of all abortions are medical, rather than surgical, meaning that most women would be able to get an abortion without having to visit a doctor. That would slash the cost of medical abortions, which average $500. The listing price of misoprostol ranges from $14 to about $90, and the drug is available for as little as $4.40 for four tablets in certain pharmacies.

Women in states that ban abortion would benefit too, because they wouldn’t need to get a doctor’s appointment in another state, or sustain higher expenses for time off work and childcare. It might also be easier to receive abortion pills via mail.

How does the FDA make a drug over-the-counter?

Surveys suggest the majority of people seeking an abortion in the US are in favor of getting over-the-counter medications for it. And American doctors appear to be pretty comfortable with the idea of medical abortion happening without healthcare supervision, too: A recent poll found that less than 20% of them think it might be unsafe, a share that declined from 22% pre-covid, likely due to witnessing safe abortions via telehealth.

But the power of making the change resides with the FDA, which has to follow a three-step review process to allow a new drug to be sold over the counter. Initial reviews have been underway for misoprostol, and research has found patients understand the directives associated with the use of the drug without professional guidance, which is an important element in establishing the safety of a drug.

Overall, the application and approval process could take years, but it would dramatically change the US abortion landscape.

The Mexican precedent

The impact of over-the-counter availability of abortion drugs can be seen clearly in Mexico, where misoprostol has been a nonprescription drug since 1985. Since then, hundreds of thousands of women have had safe abortions even prior to decriminalization or legalization in any state, says Maria Antonieta Castro, the Mexico executive director of Ipas, an international organization working to expand access to abortion.

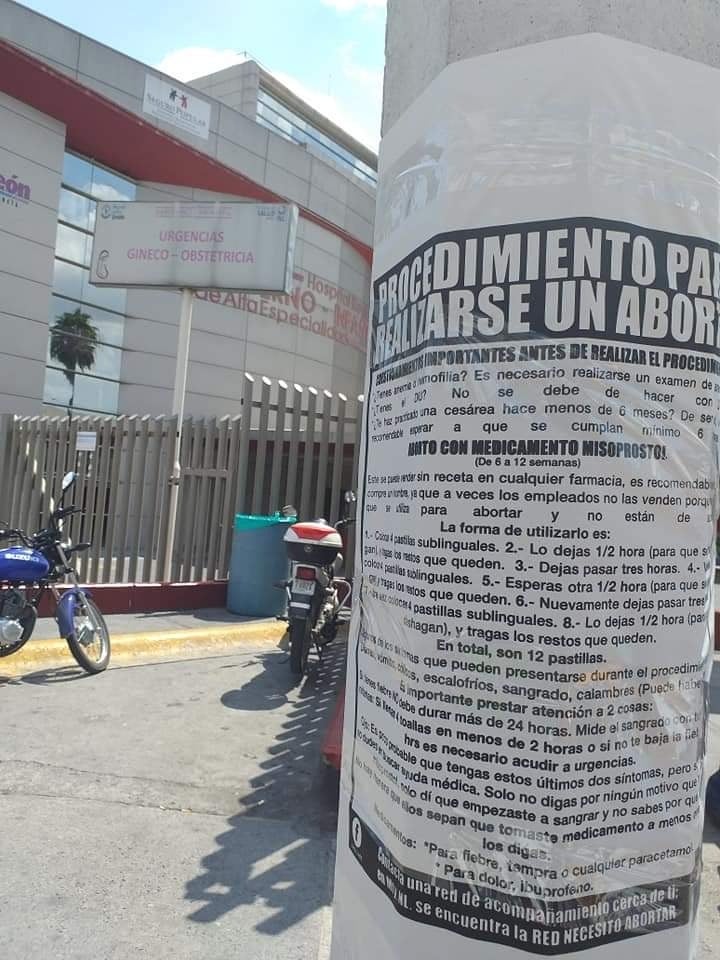

Across Mexico, informal networks are helping abortion seekers get access to the drug, or information about it. For instance, Abigail Secas, a 27-year-old activist from Monterrey, says she prints out posters with the WHO guidelines for misoprostol use and pastes them outside universities, clubs, or hospitals.

Secas is a member of Red Necesito Aborto, a network of about 50 abortion activists across the country. The network includes a safe home in Monterrey, in the state of Nuevo León, which has some of tightest abortion restrictions in Mexico. The home, nicknamed La Abortería (which could be translated as”the abortion store”) offers women a free space to have a self-managed abortion in a supportive environment, but without medical supervision. If women can’t pay for the drugs, or are unable to go to a pharmacy to buy them, Red Necesito Aborto provides them for free. The cost of misoprostol ranges from $10 to $35 for the generic version, depending on the maker and the quantities.

This kind of service would be easy to replicate in the US, too, at least in states that don’t criminalize self-induced abortions, if misoprostol were available over-the-counter.

“You don’t really need much to help a woman have a safe abortion at home,” says Sandra Cardona, who manages La Abortería, providing drugs and services for free with her partner Vanessa Jimenez. Since it opened six years ago, La Abortería has supported hundreds of women in person, and thousands more over the phone—sometimes, says Cardona, up to 300 in a month, all without complications.

In terms of safety, this scenario wouldn’t be significantly different from what already happens in the US states that allow abortion via telehealth, where a pregnant person receives a prescription for mifepristone and misoprostol without the need to see the doctor in person. Even when a medical abortion is performed in person, the patient typically takes only the first pill (mifepristone) in the doctor’s office, and is sent home with the remaining drugs to complete the procedure.

Lately says Cardona, her organization has started helping women from the US—from Indiana, Ohio, Arizona, Louisiana, Kansas, and Texas—offering guidance as they travel to Mexico to buy misoprostol. Some of the women went to La Abortería in person to take the pills, while Red Necesito Aborto gave others information of where to buy the drug, when to take it, and what to expect. But these women would be able to find help in their own country if the FDA approved abortion drugs over-the-counter.