The spreading sclerosis of the non-compete agreement

Hairdressers, camp counselors and yoga teachers: In the US, jobs like these increasingly require workers to sign non-compete agreements, a contract typically restricted to jobs with intellectual property and trade secrets to protect.

Hairdressers, camp counselors and yoga teachers: In the US, jobs like these increasingly require workers to sign non-compete agreements, a contract typically restricted to jobs with intellectual property and trade secrets to protect.

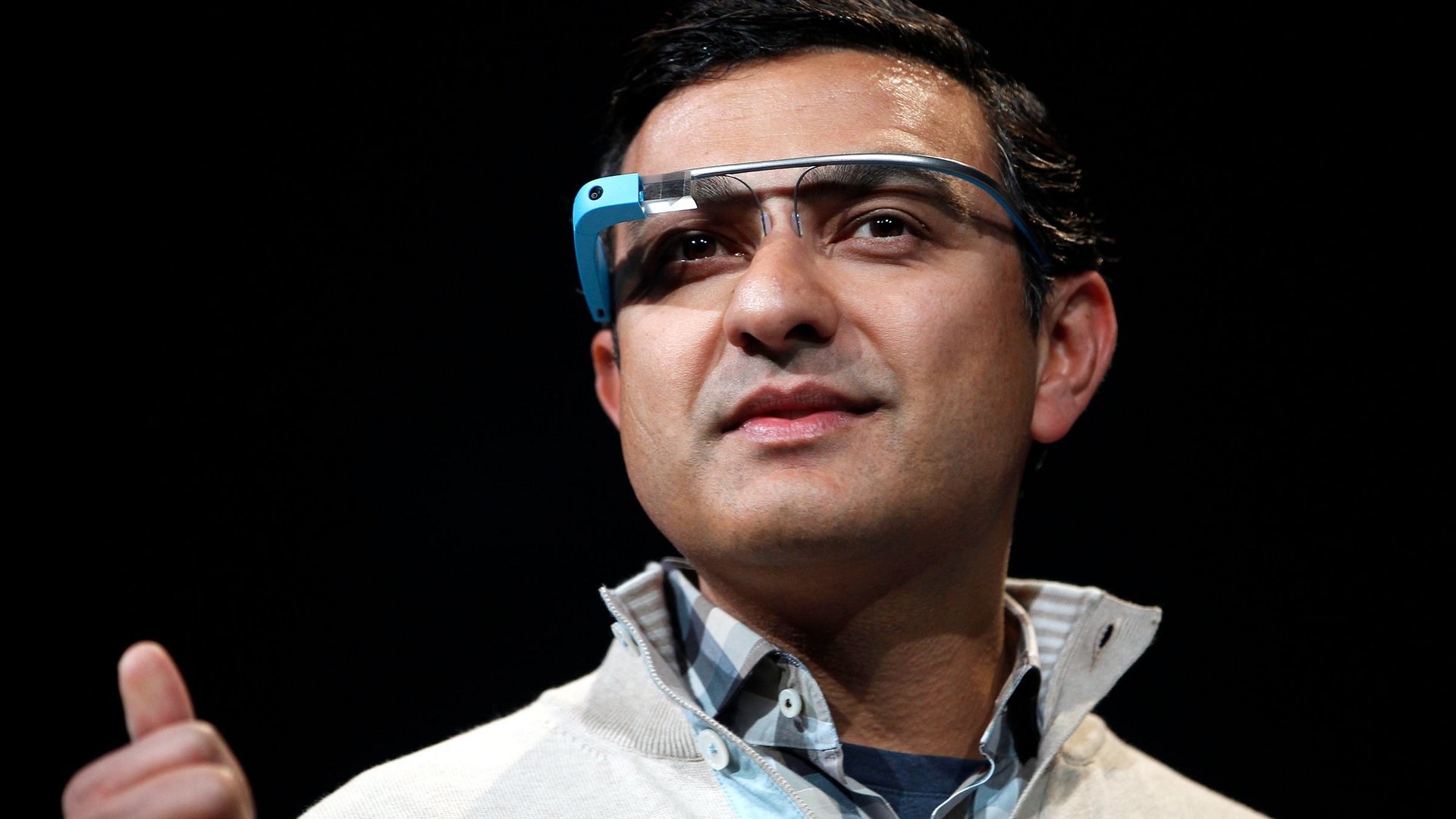

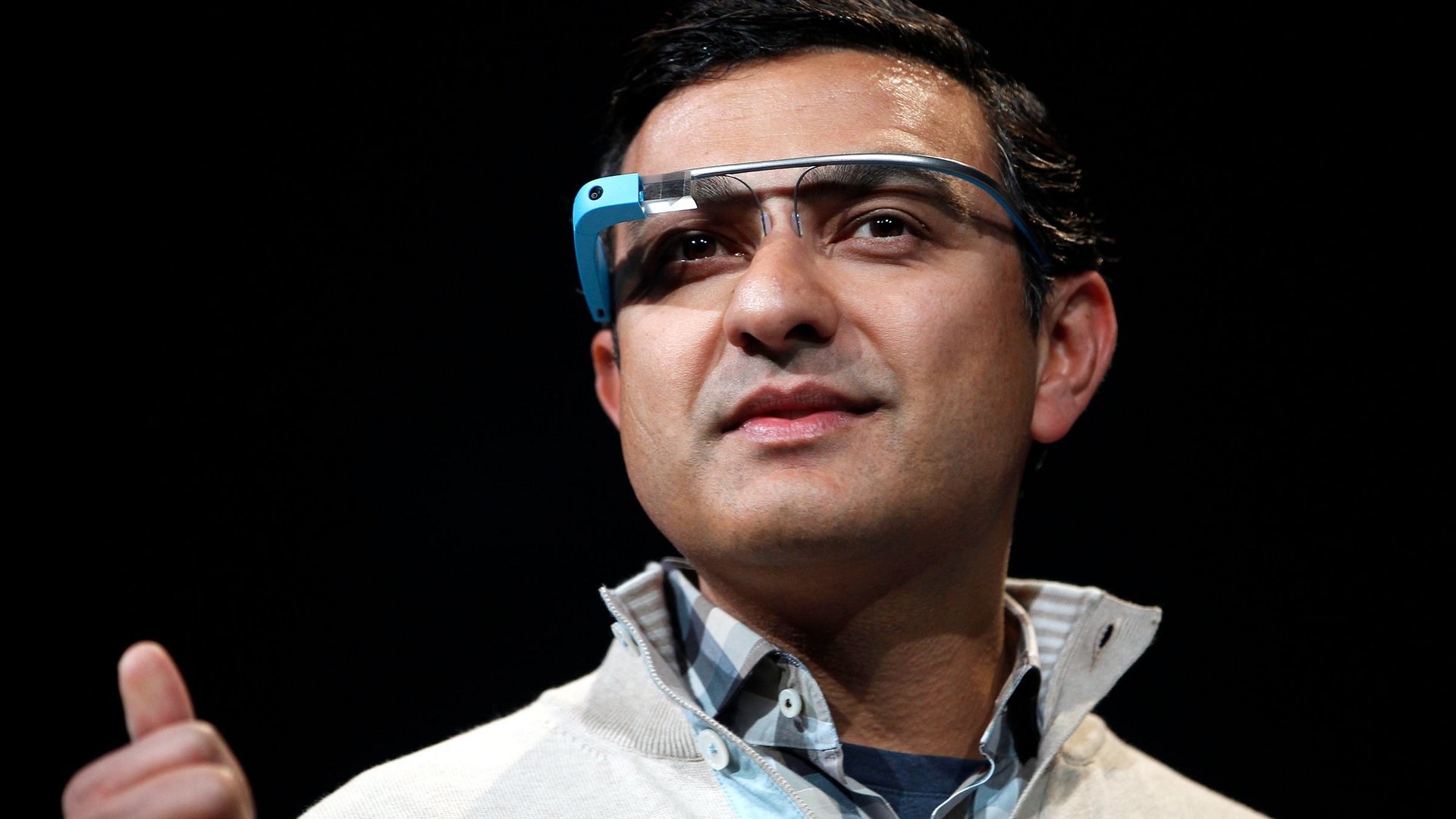

Such agreements typically proscribe a former employee from working for certain rival companies or within the same geographic area for one to two years. They can be a minor irritant for people who are paid well (former Google engineer Vic Gundotra took a year off to focus on philanthropy before joining the company, after leaving Microsoft with a non-compete), but a burden for employees who make less or whose skills are not in such high demand.

And what’s worse is that in many cases, non-compete agreements aren’t part of employment negotiations. Surveys by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers found that only three in 10 employees were told about a non-compete agreement when being offered a job; the rest said they learned about after they had accepted the job and turned down other offers, or even on the first day of work. Only one in 10 looked at the agreement with an attorney, either because of time pressure or because the company refused to negotiate the agreement. And this is a survey of skilled workers.

Moreover, even in industries where intellectual property matters, non-competes may be bad for the industry as a whole, according to a recent survey of research on the subject by MIT’s Matt Marx and Harvard’s Lee Fleming. Economists thinks that innovation can be spurred by having lots of firms in the same skilled industry working near each other; as workers move from firm to firm and mix with new people, new ideas and firms are created. Non-competes limit their ability to do that—in fact, California law makes most non-compete agreements unenforceable, and other research found that Silicon Valley has an unusually high level of inter-firm mobility for workers.

Which is probably why the late Apple CEO Steve Jobs and other California tech executives set up an informal cartel to prohibit the hiring of each other’s workers. That helps show the other problem of non-compete agreements: They appear to favor established firms, protecting them from their rivals, and making it harder for new businesses to get off the ground. Restricting these agreements, then, may spur entrepreneurship.

There is some evidence that non-competes lead to more investment in research and development (because firms are less worried about free riders), though there’s also evidence that they lead to less. But most of all, firms find non-competes a useful way to protect trade secrets: It’s much harder to prove an ex-employee violated a non-disclosure agreement than to prove she’s working at a rival company. While there is a growing sense that intellectual property is over-protected in the technology world, it does seem clear that the challenge of the non-compete is to balance a firm’s right to protect its secrets against an employee’s right to free labor.

But it might be worth harkening back to common law. Marx and Fleming report that the first non-compete clause was litigated in 1414 after an English clothing-dyer’s apprentice set up shop in the same town as his master. When the master took his erstwhile apprentice to court, not only did the judge rule against him—he threatened to throw him in jail for trying to stop someone from working.