These World Cup teams will field the most foreign-born players

Jonathan de Guzmán was born in Canada to a Filipino father and Jamaican mother. Naturally, he will represent the Netherlands at the World Cup.

Jonathan de Guzmán was born in Canada to a Filipino father and Jamaican mother. Naturally, he will represent the Netherlands at the World Cup.

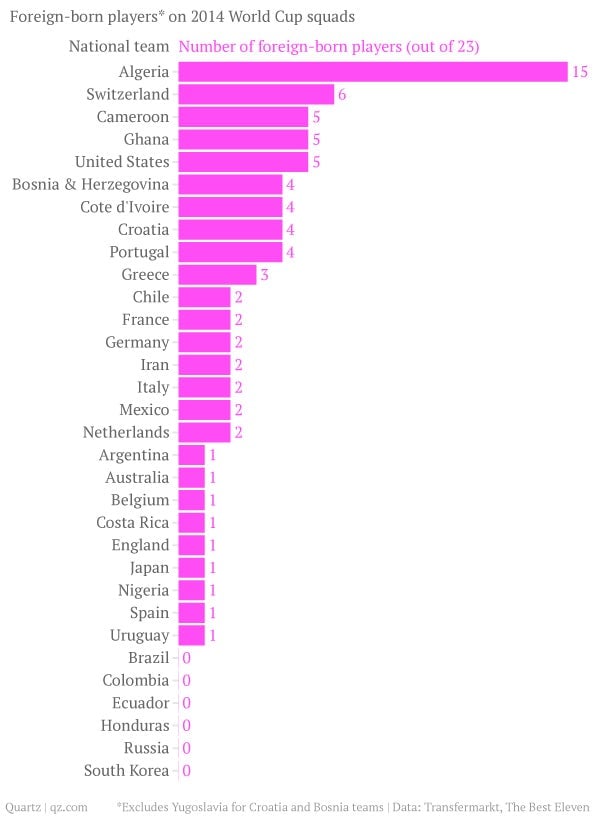

In soccer, nationality can be a fluid concept. Professionals are free to play for clubs anywhere in the world, and this increasingly also applies to national teams. De Guzmán is far from alone in suiting up for a country different from the one of his birth. Fully two-thirds of Algeria’s squad—15 of 23 members—were born in France, the largest share of foreign-born players by far:

Parentage, age, and time spent in a country all factor into which country a player can represent at international competitions. Although the rules have been tightened in recent years, all but six of the 32 teams taking part in the World Cup will field foreign-born citizens during the tournament. Just over 10% of all players at the World Cup—78 of 736—will be foreign born. (This excludes players born in the former Yugoslavia playing for Croatia and Bosnia & Herzegovina and includes Rio Mavuba, who plays for France but was born at sea as his parents fled civil war in Angola.)

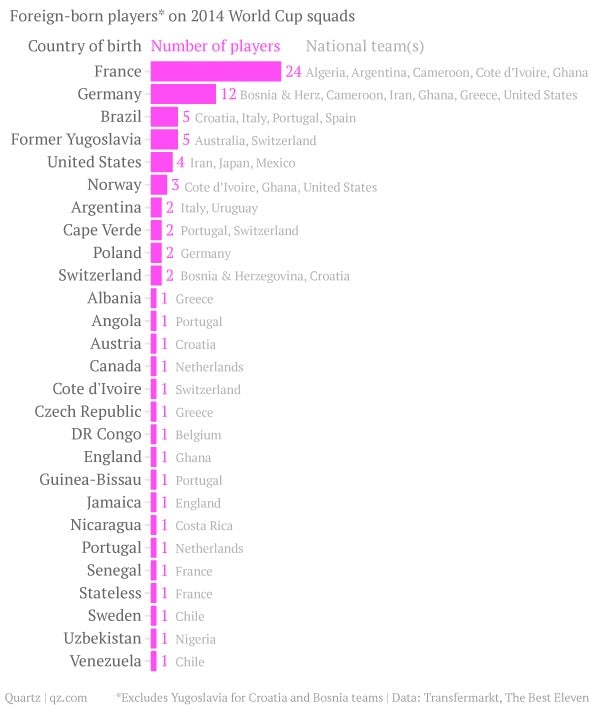

This may enhance—or complicate, depending on your point of view—rooting interests as the tournament progresses. If Germany is knocked out, there are six other teams with German-born players that supporters can back with some justification. Fans of countries that aren’t in this year’s World Cup may also feel a greater affinity to teams that field their compatriots—Norwegian-born players, for example, will feature for Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and the United States:

Predictably, the presence of foreign-born players often generates angst among certain players and pundits. And many soccer die-hards recoil in horror at the thought of supporting more than one national team under any circumstances. Given traditional rivalries on and off the pitch, perhaps it’s a step too far to expect Poles to root for Germany or Americans to back Iran because a fellow countryman happens to play under a different flag.