No one wants to buy a Father’s Day card with golf clubs on it

I’m not a dad. In fact, the idea of having kids at all felt so at odds with my life plan that a few years ago I’d laugh if you told me I’d be standing in this Duane Reade pharmacy, staring at cards illustrated with beer cans and fishing rods, looking for myself.

I’m not a dad. In fact, the idea of having kids at all felt so at odds with my life plan that a few years ago I’d laugh if you told me I’d be standing in this Duane Reade pharmacy, staring at cards illustrated with beer cans and fishing rods, looking for myself.

But then again, a few years ago I wasn’t a man. The addition of testosterone and the way my life has tilted since I transitioned has challenged me to rethink masculinity and identity in every dimension—including fatherhood. I may be uniquely positioned, as a transgender man, to design my masculinity consciously—but I’m not immune to socialization, and I’m also not alone in this historical moment where we all seem to be asking: What, exactly, makes a man anyway?

In fact, in the years since the “mancession” resulting from the financial crisis and economic meltdown, flexibility in parenting roles are often cited as evidence that the role of men in society has undergone a radical shift. There’s no denying that we are living in an era of more engaged dads—and that’s resulted in a reexamination of the role and influence of fathers. Paul Raeburn, author of Do Fathers Matter? What Science Is Telling Us about the Parent We’ve Overlooked, argues, basically: Yes, and way more than we think. Though aspects of his argument can feel a bit gender essentialist (women engage in more risky sexual behavior, he says, when a father is “disengaged”), it’s impossible to imagine this generation of post-recession babies all grown up and standing in a cards aisle, looking at Father’s Day offerings that are all golf clubs and tool boxes.

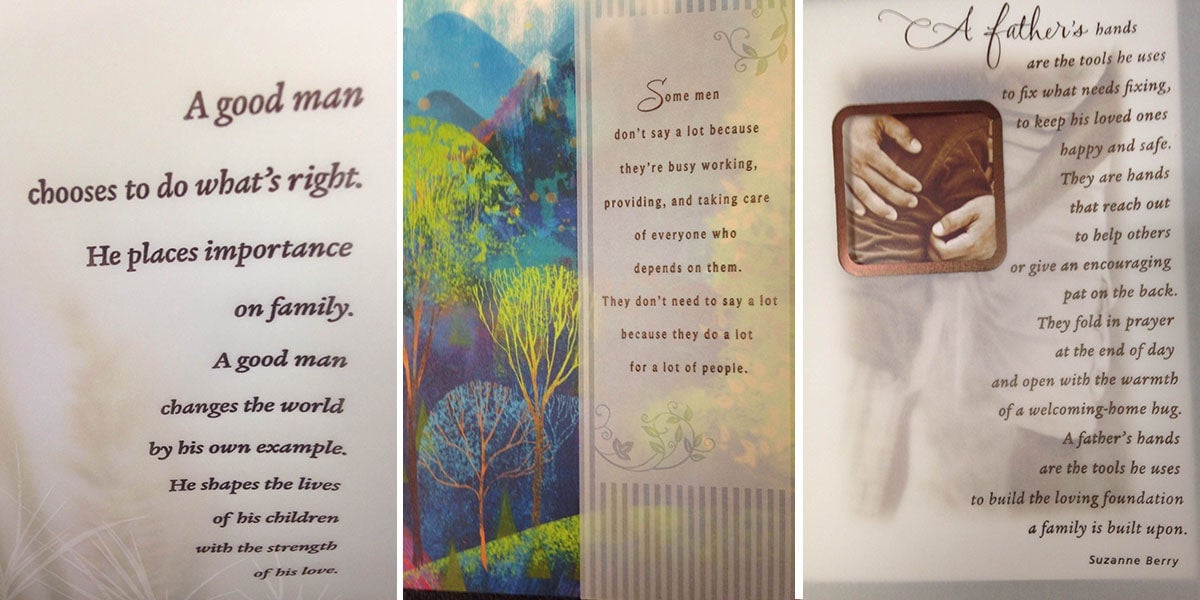

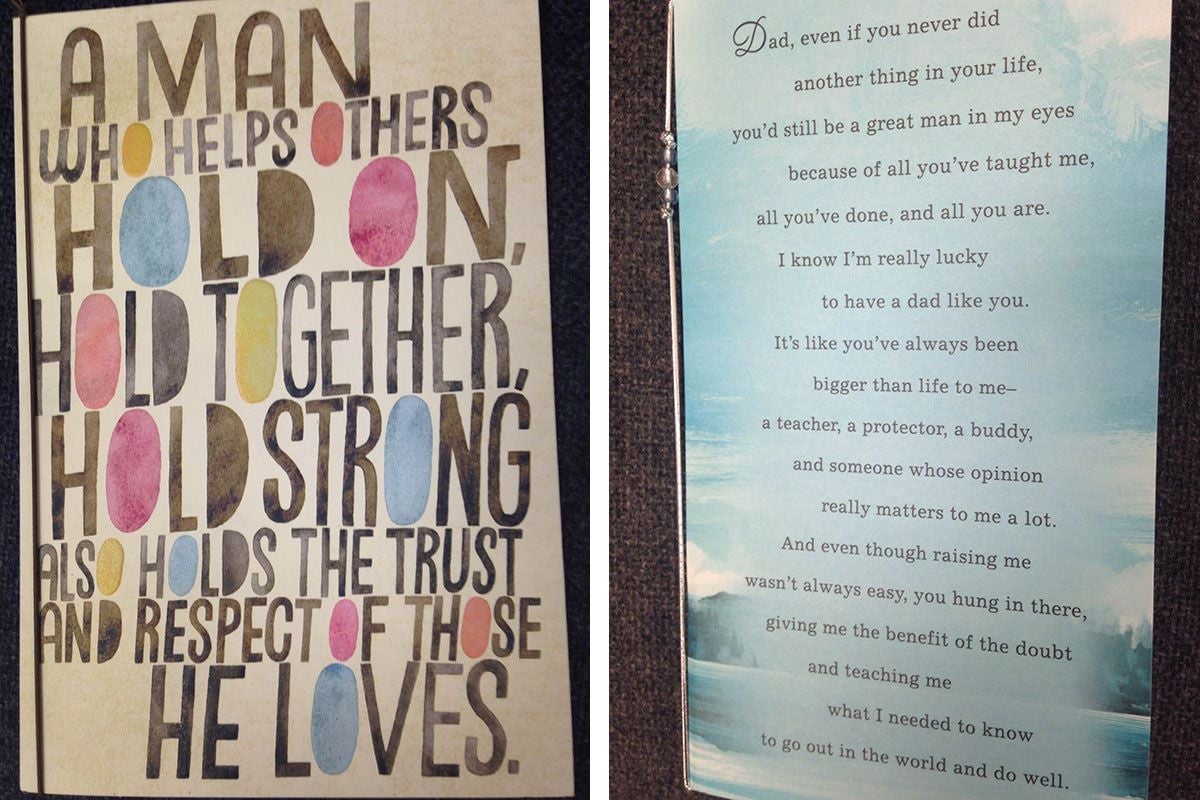

The dissonance between the attitudes of younger fathers that I know and the corny platitudes lauding distant disciplinarians every June in drugstores across America is striking. Whose masculinity is this, anyway? When we buy a card that says “A father’s hands are the tools he uses to fix what needs fixing, to keep his loved ones happy and safe,” who are we talking about? More importantly, when we overlook our fathers’ generation’s tenderness in order to thank them for being a “protector and buddy,” what idea of masculinity have we bought into?

The truth is, I’ve learned everything I know about fatherhood from my friends. The fathers I know send me pictures of their sons in dresses. They are designers and poets and small business owners, and they work from home so that they can change diapers and carry babies on their backs while mowing the lawn. They mow the lawn and they also mix the formula.

They are co-parents, and some of them fix things with their hands but all of them know to hold their daughters so that they face out, not in—flipping the message we give young girls that they need to be protected from the world instead of explorers of it. They are raising boys who will be better men and who, someday, will stand in a store just like this one, and buy cards that thank them for it. I hope they’re covered with footballs and pacifiers and beach toys and say things like: “You showed me that there’s no right way to be myself.”

That’s the Father’s Day card I’d want. You know, someday.