Counting calories won’t help you lose weight

“Coca-Cola is taking on obesity,” read the AP coverage of the company’s new commercial this week, “with an online video showing how [much] fun it could be to burn off the 140 calories in a can of its soda.”

“Coca-Cola is taking on obesity,” read the AP coverage of the company’s new commercial this week, “with an online video showing how [much] fun it could be to burn off the 140 calories in a can of its soda.”

The scene puts a covey of Californians around a comically oversized bicycle on Santa Monica beach. They stationery-cycle in montage for 20 to 30 smiling minutes each (depending on each person’s size and vigor), until they’ve burned the requisite number of calories to coax an aluminum can along a whimsical Rube-Goldberg-type trapeze. The can eventually reaches the big payoff, when a giant disembodied hand bestows to the pedaler Coca-Cola.

Not everyone thought it looked fun. “They’re showing exactly why you wouldn’t want to drink a Coke,” brand consultant Laura Ries said, presumably not while biking. “Twenty-three minutes on a bike is not fun for most people.” (23 minutes was the average time required for a 140-pound person—though as Adweek noted, the average 20-year-old man weighs 196 pounds, and the average woman of the same age weighs 166 pounds.)

It’s also uncomfortably evocative of a lab experiment where hamsters run on a wheel until they are delivered a pellet of, say, opium. But others in the foodie world were less skeptical of the marketing move than they were enraged by it. I probably would have been too, if I were still capable of strong emotions.

Because asking how much time it takes to burn off the calories in a can of Coke is like asking how many Hail Marys it takes to uncheat at poker. I think it does something for your immortal soul, but if you get caught you’re still going to get punched in the stomach. Even if you give everyone their money back, it’s not over. Best case scenario, future games are going to be awkward.

“This is a light-hearted, down-to-Earth message,” Coke spokeswoman Judith Snyder told USA Today. “There are fun ways to burn calories. We want to be very clear that this is not at all a dig at nutritionists but a fun, lighthearted way to present this message.”

It is, though. It’s a dig, Judith. Coca-Cola is not taking on obesity; it is taking on its rotting public image. The campaign is absolutely a dig at the work of nutritionists, in that “Keep eating junk food, just exercise the calories off” is exactly the message that public-health advocates have been fighting in recent years, because it’s not the legit proposition it might seem to be.

***

I like the sounds of the words diet-sage doctors use. I like their deliberate scrubs and airbrushed faces on billboards and book jackets. And I relate to Joan Didion’s notion of being a writer feeling no legitimate residency in the world of ideas. My eyes are drawn to the periphery of the weight-loss market, the absurd tag-lines of bestselling-hopeful books with titles like My Beef With Meat, to the drama in scientists slinging mud at one another with professionally acceptable level of passivity to mitigate their aggression. That’s what I like to write about.

But writing is necessarily, Didion again, “an aggressive, even hostile act … an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s.” Like it or not, you are always imposing an idea. If writing is an invasion, then doing a TV or radio appearance is scorching the earth. There an idea is meant to be extracted in its most distilled form, on any number of the billion talking-head shows, in two to five minutes. Clearly, concisely, without caveats.

These appearances were never part of any plan I made for myself, but they come with writing, and to my mother it’s pretty much the height of success. So I do them, but I end up answering questions in ways that visibly/audibly disappoint hosts. Just tell me what’s good and what’s bad, the audience seems to want of its health media. “It’s complicated” is not a helpful answer. Last weekend I was on MSNBC talking about my feature “Being Happy With Sugar,” and the interviewer T.J. Holmes, doing his job perfectly, was trying to extract a stance on just how evil sugar is. And, it’s complicated. Sugar is “toxic” insofar as anything is toxic at the right level, and thinking of it as toxic may or may not be a helpful construct.

“What’s one of the biggest misconceptions out there that you wish you could turn around?”

Well, I’m not sure what your conceptions are? After a few minutes, Holmes said I was killing him. I was, I’m sure. He was killing me. Sugar is killing us all. To some degree. I hope the invasion of my sensibilities was more aggressive to Holmes than it was to the people watching weekend daytime news. But it helped me hone this idea that I have to deal in ideas in a frank, consumer-oriented way sometimes if I’m going to be productive to public health.

On Wednesday I got to do a longer segment on the local NPR affiliate alongside Dr. David Ludwig, a professor at Harvard Medical School. That was a good discussion, as it always is with host Kojo Nnamdi. Ludwig is a man of ideas, important ideas that he’s been saying for a long time. Here’s the most interesting part:

NNAMDI: Many of us have been led to understand that weight gain or loss is simply a matter of willpower, our ability to restore balance to that equation of the calories that go in our bodies and the calories that we use and go out. You’ve done a lot of research that suggests our basic understanding of that equation is off kilter. How so?

LUDWIG: … Very few people can lose weight over the long term with low-calorie diets. And those who can’t are blamed for lack of discipline and willpower. So, according to an alternative view, weight is controlled like body temperature and a range of other biological functions. Eating too much refined carbohydrate has, by this theory, raised insulin levels and programmed our fat cells to suck in and store too many calories. When this happens, there are too few calories for the rest of the body. So the brain recognizes this and triggers the starvation response. We experience that as becoming excessively hungry and our metabolism slows down. … Eventually we succumb to hunger and overeat. So a better approach, if this theory is correct, is to address the problem at its source by cutting back on the foods that are over-stimulating our fat cells: the refined carbohydrates like grains, potato products, concentrated sugars, especially the refined grains. And by eating this way, we can basically ignore calories and let our body-weight control systems do the work.

NNAMDI: Is it oversimplification to say that your research suggests we’re getting hungrier because we’re getting fatter?

LUDWIG: [No,] that’s right.

Ludwig and co-author Mark Friedman wrote about this in a New York Times article last month headlined “Always Hungry? Here’s Why,” saying that the “simple solution” ingrained in people who want to lose weight “is to exert willpower and eat less.”

The problem is that this advice doesn’t work, at least not for most people over the long term. In other words, your New Year’s resolution to lose weight probably won’t last through the spring, let alone affect how you look in a swimsuit in July. More of us than ever are obese, despite an incessant focus on calorie balance by the government, nutrition organizations, and the food industry. … As it turns out, many biological factors affect the storage of calories in fat cells, including genetics, levels of physical activity, sleep, and stress. But one has an indisputably dominant role: the hormone insulin.

The food industry didn’t necessarily focus on calorie counts until recently, but it has definitely embraced it now. Twix and Oreos come in 100-calorie packs. Coke tells you exactly how to burn its calories off. It’s better than nothing, right? Here’s my foray into the realm of nutrition ideas: Eating based on calories is a problem. That’s what I should’ve told T.J. Holmes. It’s really an aggregate of what many nutritionists and writers are saying right now, but: Calorie counting doesn’t work for most people, and it’s manipulated by companies marketing junk. It’s not a good way to think about food.

Highly refined carbohydrates—chips, crackers, white bread, soda, rice—spike our blood sugar. That spike makes the pancreas produce tons of insulin. That insulin tells our body to store energy as fat. Subsequently, as Ludwig and Friedman write in the current Journal of the American Medical Association, “energy expenditure declines and hunger increases, reflecting homeostatic responses to lowered circulating concentrations of glucose and other metabolic fuels. Thus, overeating may be secondary to diet-induced metabolic dysfunction.” That is, refined carbs make us eat more, which makes us fat, which makes us eat more, and so on.

NNAMDI: James, the last time you joined us we talked about the addictive power of foods, whether Oreos are really kind of maybe like crack cocaine. It seems that part of this conversation is about a habit many of us develop in thinking that all calories are just calories, regardless of their sources. There are a lot of people out there now saying, no, all calories are not created equal. What are they saying and why is this significant?

HAMBLIN: It goes right in line with what Dr. Ludwig is saying, that certain calories will cause fluctuations in the body’s hormones and blood sugar levels, that will only augment future hunger. So you might be able to temporarily eat a low calorie diet of high-sugar foods but it’s going to be unsustainable, you’re not going to feel good. You’re probably going to feel constantly hungry. And after a few weeks, probably go back to eating more. Whereas if you focus on eating a more balanced whole food diet, you will sustain that longer. And ultimately, you know, we’re not proposing that this is overturning the first law of thermodynamics. You will need to burn more calories than you consume [in order to lose weight]. But it’s about where you focus that intention of eating. If you think about the calories, I think you tend to make choices to say, well, I can only eat 200 calories now, I’d really like to get that as the most delicious 200 calories possible. I’m going to eat 200 calories of ice cream or soda. …

LUDWIG: This is, of course, an argument the food industry loves because, by it, there are no bad foods.

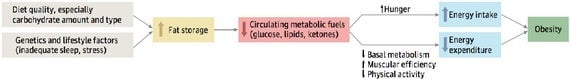

So the old paradigm of weight gain/loss, according to Ludwig and Friedman, looked like this:

And the new one looks like this:

***

Exercise, too, is about more than burning calories. Ludwig has a good way to think about it:

NNAMDI: Allow me to go to Mark in McLean, Virginia. Mark, you’re on the air.

MARK: Hey, Kojo. I wanted to speak about eating clean and sort of healthy eating, in the way that a bodybuilder might eat. I’m currently on a diet and exercise campaign to drop a few pounds. And, you know, I’m eating healthy. I’m eating greens, dark greens. I’m eating fruits, I’m eating whole grains, and I’m eating protein—chicken and fish. And I’m exercising. I’ve never been a big juice drinker or a soda drinker. I don’t do ice cream. Those are the anti-clean-eating foods. So I wanted to ask your panel to comment about eating healthy in combination with exercise as an effective approach to weight loss.

LUDWIG: I think some physical activity is great. I am a strong advocate of it. I think physical activity is, oftentimes profoundly misunderstood in its role in weight management. To burn off the calories in one super-sized fast-food meal, it takes [running] a full marathon. You know, we’re much more efficient in holding onto calories than we can consume a tremendous amount quickly. And the body, through evolution, doesn’t want to be wasteful with its calories. So when you’re at extremely high levels of physical activity, you can begin to have a very substantial impact on calorie balance. But for most people, physical activity has a whole nether role. It’s not so much burning off calories as is it is in tuning up our metabolism, lowering insulin levels, promoting insulin sensitivity and helping bring those fat cells back into line in behaving more cooperatively with the rest of the body. So, physical activity is good if it’s linked to a diet that lowers insulin levels and helps control hunger. But by itself, [it’s] not a very good way to lose weight.

***

So yes, the first law of thermodynamics remains immutable. Energy balance is a true concept. A person will not lose weight if they eat more calories than they burn, and vice versa. But it’s just not a helpful way to think about food, given the fact that foods all around us are labeled with a calorie number that doesn’t fully tell us how that food will affect our metabolism and future hunger.

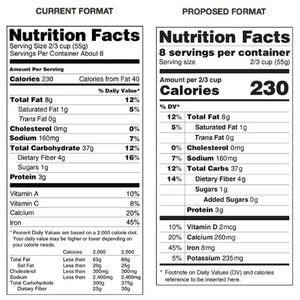

The proposed new FDA nutrition labels make the calorie number larger. That seems like a mistake. Focusing on calories puts the emphasis in the wrong place. The biochemistry is complex, but the way to think about it is not. Don’t focus on calories; focus on food choices. Eat real food, no added sugar, and you can really forget the numbers.

In 1924 the Journal of the American Medical Association published a prescient idea similar to what Ludwig (and others) advocate. It read:

“Are you ashamed of your weight?” This question is the backbone of an attitude that is rapidly attaining prominence in many parts of the country. Obesity is being made the subject of attack from many quarters. From one direction, the threat of diabetes is heard; from the insurance office, the implication that he is liable to be a “bad risk” greets the corpulent person, while his own discomfort on vigorous effort serves as an even more immediate reminder of the consequences of lessened activity. The dressmaker and the tailor dispense additional reminders in the form of friendly, though unwelcome, gibes that drive the victim of adiposity to seek relief by some means. The outcome has been an unprecedented demand for “reduction” treatments, with a preference for ways that are quick and easy. The quack has not been slow to take advantage of his opportunity to extract a rich reward from the gullible.

When we read that “the fat woman has the remedy in her own hands—or rather between her own teeth,” and that “she need not carry that extra weight about with her unless she so wills,” there is an implication that obesity is usually merely the result of unsatisfactory dietary bookkeeping. When food intake exceeds energy output, a deposit of fat results. Logic suggests that the latter may be decreased by altering the balance through diminished intake, or increased output, or both … The problem is not really so simple and uncomplicated as pictured.

But that’s the simple paradigm that, 90 years later, Coke and everyone else peddling empty nothing “foods” as simply part of the calorie count are perpetuating.