Iraq shows that the global economy needs Saudi Arabia again

The US shale oil boom is said to be reducing the world’s long-running dependence on Saudi Arabia. But the upheaval in Iraq appears to be reviving the kingdom’s centrality to the global economy.

The US shale oil boom is said to be reducing the world’s long-running dependence on Saudi Arabia. But the upheaval in Iraq appears to be reviving the kingdom’s centrality to the global economy.

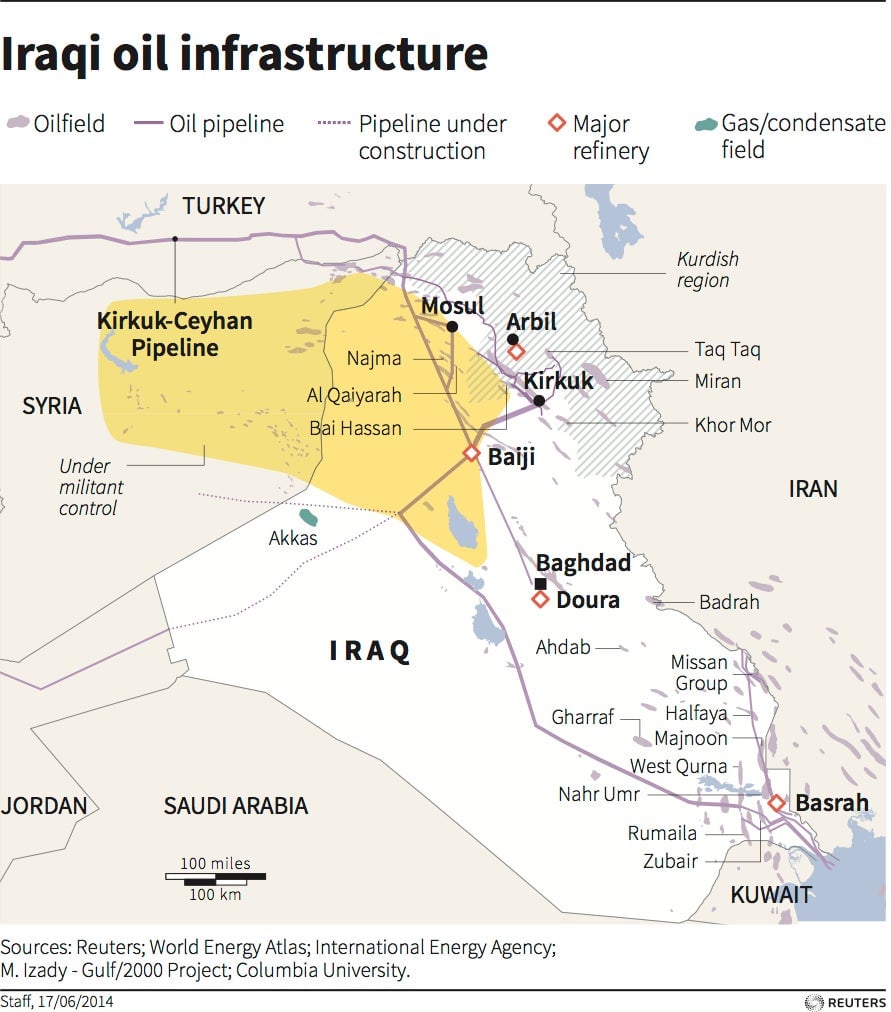

Iraqi militants yesterday attacked Baiji, a large oil refinery that serves a quarter of the country’s fuel and electricity needs. Despite the violence, many analysts have taken comfort in that the trouble is concentrated in northern Iraq, well away from the country’s oil-producing regions, which are almost all in the south. The overwhelmingly Shiite south lacks the indigenous Sunni population whose support has made the militant Sunni offensive possible.

But that confidence may be misplaced. BP and ExxonMobil have ordered a partial evacuation of oilfields in southern Iraq. And, in a note to clients, Citi’s Seth Kleinman suggests that, even though they do not necessarily face a direct threat, foreign oil companies are less likely to invest the billions of dollars required for new Iraqi production amid such insecurity. Baghdad delayed bidding (paywall) scheduled for today for rights to produce oil and build a refinery at southern Nassiriya, saying it needs more time to make the tender succeed. Among the reasons for industry reluctance are the violence and Iraq’s frustratingly cumbersome application process.

“Arguments that the south is more secure as it is a Shiite stronghold may not be sufficiently reassuring to oil companies already complaining about onerous terms and painfully slow bureaucracies that have to be negotiated for approvals,” Kleinman wrote.

Enter Saudi Arabia. The Saudis have spent the last few decades largely unchallenged as the largest oil producer on the planet. Currently, the Saudis produce about 10 million barrels of oil a day and say they have the capacity to produce another 2.5 million. That spare production capacity is by far the most of any petrostate, giving the Saudis immense leverage as a swing producer in a crisis.

Until a couple of years ago, some Saudis spoke of adding yet another 2.5 million barrels a day of capacity, giving them 15 million in all. But if there ever were such plans officially, they have been shelved since the recent US shale revolution added millions of barrels a day to US production. In April, the US produced 11.2 million barrels (paywall) of oil and gas liquids a day, the most since 1970. It has been said that, four decades after the Arab oil embargoes, the US will soon become an oil exporter and no longer beholden to the Persian Gulf, and specifically Riyadh.

But a series of geopolitical disruptions including in Libya and Nigeria have canceled out those gains. And after the upheaval in Iraq analysts now believe that such disruptions will remain a factor for many years.

If that is the case, Saudi Arabia’s oil will again be central to the global economy. Specifically, the world may need Riyadh to invest the billions necessary to increase its production capacity to 15 million barrels a day.

But Kleinman doubts the Saudis will come to the rescue. Quite apart from any potential plan to increase capacity, Kleinman says that the Saudis won’t be able to supply even the full 12.5 million barrels a day of capacity that they claim they can produce. “Given that the market has never seen Saudi Arabia hold production over 10 million barrels a day, a combination of skepticism and caution seems warranted,” he writes.

Other analysts say that such worry is unwarranted—that US and other non-OPEC oil will continue to pour onto the market and smooth out the impact of disruptions without any added Saudi help. But for now, the pessimists have the momentum on their side.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said militants had “seized” Baiji, but at publication time they had not yet taken control and fighting was continuing.