Should the US government be bailing out my parents’ flooded basement?

Hurricane Sandy made landfall more or less right over my childhood home in Margate, New Jersey, an island community just a few miles south of Atlantic City. I watched in horror as pictures of flooded streets surfaced and fretted about the damage my parents would find when they returned home. As it happens, their big brick house–on the beach block but ironically one of the highest points on the island—only conceded the ground floor basement, which saw one or two feet of water. Given that this is the first flooding they’ve had since moving in in 1992—not to mention the devastation that took place on other barrier islands in New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—we consider ourselves lucky.

Hurricane Sandy made landfall more or less right over my childhood home in Margate, New Jersey, an island community just a few miles south of Atlantic City. I watched in horror as pictures of flooded streets surfaced and fretted about the damage my parents would find when they returned home. As it happens, their big brick house–on the beach block but ironically one of the highest points on the island—only conceded the ground floor basement, which saw one or two feet of water. Given that this is the first flooding they’ve had since moving in in 1992—not to mention the devastation that took place on other barrier islands in New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—we consider ourselves lucky.

That said, flooding is frequent enough on the island that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has struck a deal with the county to offer insurance for buildings as part of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Flood insurance comes separate from most home insurance, and the vast majority of policies are provided through NFIP. The program was initially established to make sure flood victims weren’t dependent upon the generosity of their family and friends after a natural disaster, and to reduce the cost of government disaster-relief spending in vulnerable areas. In 1973, the government began forcing most homeowners in flood zones to buy insurance with their mortgages.

However, NFIP in its current state is in shambles. Before the storm, the program owed $17.8 billion to the national government–much of which was accumulated after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. And payouts to restore New York and its environs, one of the wealthiest metropolitan areas in the world, will no doubt push the fund deeper underwater.

The US is not alone in having problems with flood management. Two-thirds of land in the Netherlands is located below sea level, and during the Great Flood of 1953 (see news video) nearly 2,000 people died after a storm and a spring tide dramatically raised water levels. That’s about as many people as were killed by Katrina and its aftermath—but as a share of national population, the Dutch death toll was nearly 30 times bigger. The country’s response was to embark on a huge bout of coastal remodeling, to encourage a “managed retreat” from unsustainable areas and improve dikes and seawalls to standards far above the standard minimum for preventing an equal flood.

The Netherlands now refuses to see flooding as a natural but unavoidable phenomenon. “To the average citizen flooding is not a natural disaster that still can happen but with a very small chance,” writes the country’s Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management (pdf). “This perception has changed in the direction of considering disasters from something that can happen to something that must not happen again,” like plane crashes or nuclear plant disasters. To the Netherlands, constant rebuilding of property would be unacceptable. Instead, the country will spend $100 per person per year for the next century to beef up its flood protections.

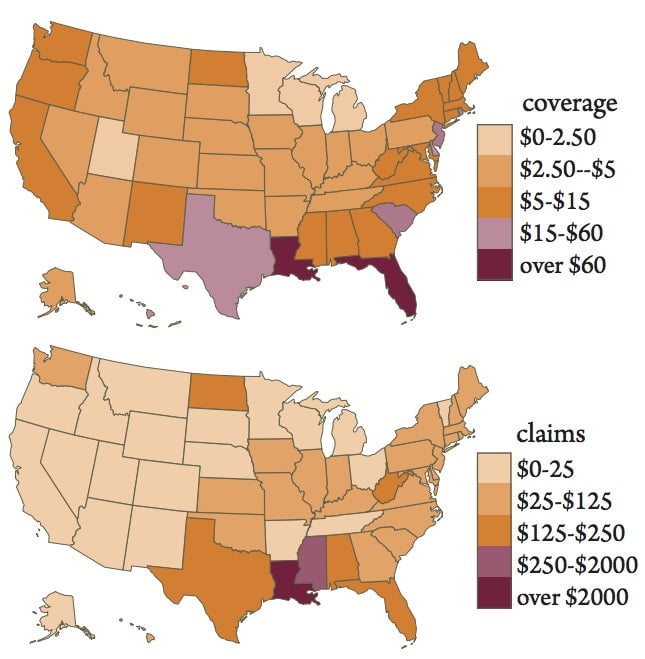

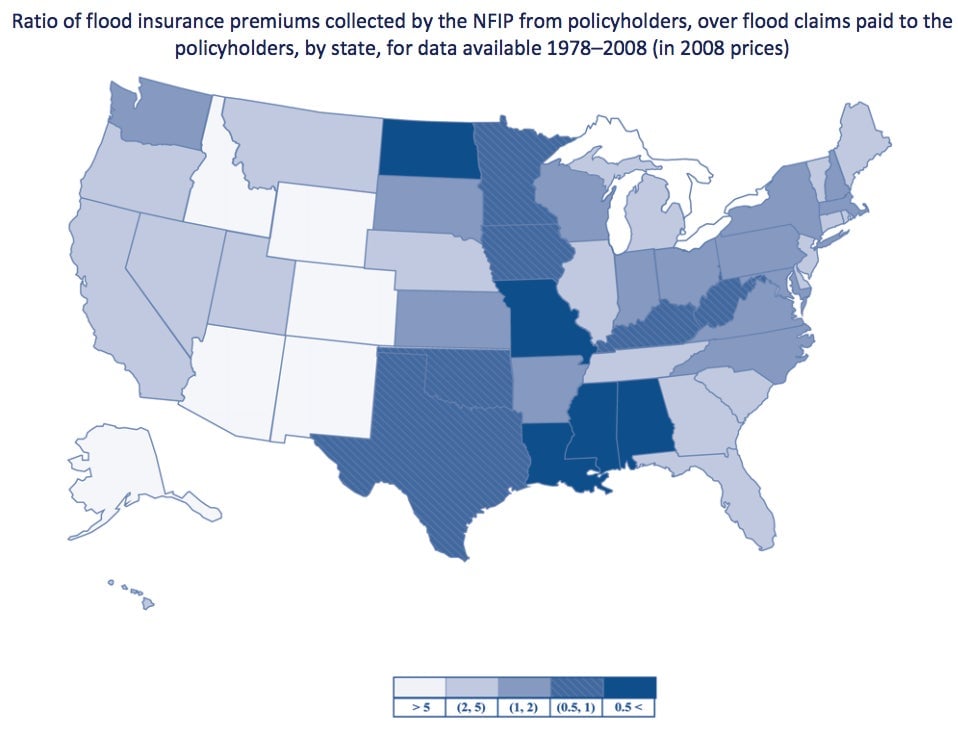

The US, by contrast, is fixated on rebuilding flood-damaged homes rather than preventing future damage. As it stands, “repetitive-loss properties,” defined as those that have suffered damage up to 25% of their total value twice in 10 years, “account for just 1 percent of NFIP’s insured properties but are responsible for 25 percent to 30 percent of claims,” according to a report published (pdf) by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2011. The bulk of those properties are located along the Gulf Coast (which has the highest number of claims), and subsidized by properties up north (where there is high coverage but a low volume of claims).

Another way to look at this is in the ratio of coverage per capita to claims per capita, which shows more clearly which states—the darkest ones in the map below—are getting the most insurance bang for their buck:

Why is that? In part, it’s because current disaster management policy is more aimed at restoring property as quickly as possible than it is at preventing future losses. Just take the case of Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, a community on the Mississippi River delta just outside New Orleans where much of the land is below sea level. The county was flooded by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, then devastated by Hurricane Isaac in August of this year.

View from boat. I’m told more than 100 homes back here. Water higher than 1st floor. Least 10 feet. #wfaaisaac twitter.com/jebetz/status/…

— Jonathan Betz (@jebetz) August 29, 2012

The US Army Corps of Engineers has scrapped proposals to beef up non-federal levees in the area, saying such plans were not economically feasible. Levees do exist around Plaquemines Parish, but the federal government has so far refused to bear the expense of building them up to prevent more flooding. But the homes in the area will be rebuilt, because they are covered by NFIP. Not only that, but Louisiana Insurance commissioner John Donelon said the premiums homeowners pay on these policies won’t be increased after Isaac.

Hence arises a paradox: the government won’t pay for flood prevention, but it will pay for flood damage that the prevention might have prevented. The GAO has argued that FEMA’s policies frequently amount to subsidies for homeowners in high-risk areas, instead of diminishing the future cost of flood clean-up to the taxpayer. “NFIP currently does not charge all program participants rates that reflect the full risk of flooding to their properties…to encourage program participation. While the percentage of subsidized properties was expected to decline as new construction replaced subsidized properties, today nearly one out of four NFIP policies is based on a subsidized rate,” Orice Williams Brown, the Director of Financial Markets and Community Investment at GAO, told Congress last year.

Not all repetitive-loss properties are the same. Many can be built up or altered to handle flood waters–in fact, the NFIP maintains a Best Practices Portfolio to tout innovations that have helped homeowners survive even the worst storms in areas prone to flooding.

But some homeowners realize that their properties are bound to flood repeatedly. In such cases, FEMA aid has sometimes been used to buy out their houses. But after storms many states refuse to reimburse (pdf) these flood victims the full value of their house to relocate, which often encourages them to rebuild in the same spot instead.

And while properties insured by NFIP are required in many cases to build higher or use different materials when making alterations worth more than 50% of the value of their homes, many are “grandfathered in” at old insurance rates. Further, owners of homes that frequently flood have faced red tape even when they were willing to relocate. Because there is so little funding available for such preventative measures, FEMA often denies buyouts, only to offer aid all over again, even for houses that flood multiple times per year.

The house I grew up in is not like that. Arguably, the town’s sea-walls could be strengthened and improved to more reliably keep water out of the streets, but hurricanes are rare and disastrous events, and living on the shore has risks. For my parents, it’s about the same risk as having a big, old tree outside one’s house (ironically, they can’t grow one because of the home’s proximity to the salt and wind), and so insuring against the rare, freak storm is worth it. However, offering flood insurance at low rates across the country encourages taxpayers to take on an undue burden for homeowners. That the US offers emergency aid is a blessing, but a better flood insurance policy would more adequately distribute the risks of living in a flood zone on homeowners who decides to live there.