China’s growing food demands stoke fears of a global factory farming boom

Late last year, in the wake of a Chinese state-owned pork company’s controversial takeover of US-based Smithfield, Mother Jones magazine posed a provocative question: Since US pork production costs are below China’s, and China’s meat consumption was growing fast, did the deal mean that the US was becoming China’s factory farm?

Late last year, in the wake of a Chinese state-owned pork company’s controversial takeover of US-based Smithfield, Mother Jones magazine posed a provocative question: Since US pork production costs are below China’s, and China’s meat consumption was growing fast, did the deal mean that the US was becoming China’s factory farm?

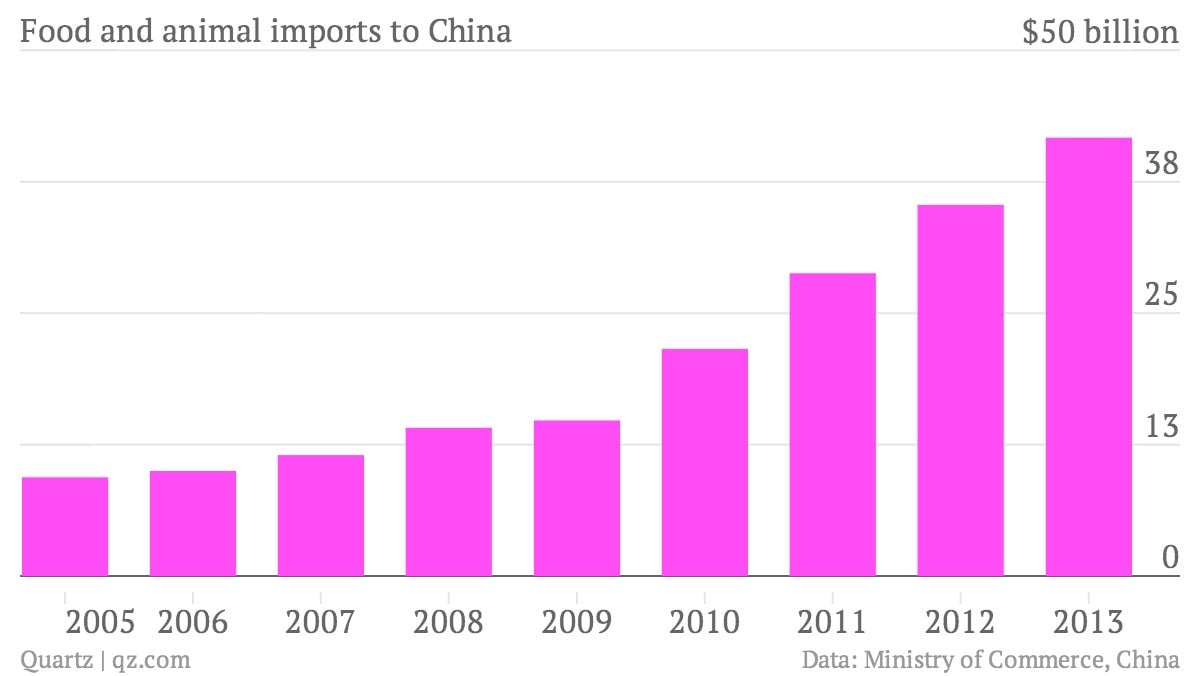

As China’s appetite for imported food grows, that question is being asked about much more than pigs, and much farther afield that just the US, as producers face the threat of growing environmental problems as they attempt to satisfy Chinese demand.

High production targets based on exports to China have raised fears for Scotland’s salmon farmers, because environmental rules designed to protect the industry might have to be weakened to meet production increases of 32% over the next six years, which would be needed to yield promised exports to China. Scotland’s salmon farms have already been plagued with outbreaks of sea lice and are prone to accidentally releasing fish into the wild.

On the other side of the world, in New Zealand, China’s consumption of dairy products has been a huge boon to the economy. Dairy and forestry products contributions to GDP grew four-fold (pdf., page 3) largely thanks to China. But once again, the industry’s plans to keep up with China’s future demands is raising concerns. One proposal from dairy giant Fonterra, New Zealand’s largest company, is to put New Zealand’s famously grass fed, free range cattle into “indoor housing”—essentially creating factory farms where none had existed before.

How nations balance the economical benefit of growing food for China with the potential environmental effects will only become a more pressing question in years to come.

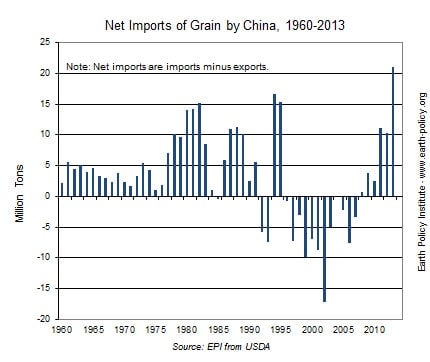

China’s appetite for foreign-produced food continues to grow, as its companies have embarked on a string of successful overseas food acquisitions, including a New Zealand dairy farm, an Isreali packaged food company, and last year’s blockbuster acquisition of Smithfield. Recent trade agreements mean that China will soon get an influx of cherries from British Columbia and sausage and ham from France. Faced with a dearth of arable land to feed its vast population, China’s corn and wheat imports are also increasing.

China’s wealthy middle and upper classes are driving much of this demand, but so is a reduced ability to grow food in China. About 20% of China’s agricultural land is already polluted, rivers are drying up or being diverted for industrial use, and these problems are only getting worse.

“Can the world feed China?” the Earth Policy Institute’s Lester Brown recently asked, a follow-up to the his essay (“Who will feed China“) that is credited with sparking Beijing’s agricultural reforms 19 years ago. China’s grain consumption is growing by 17 million tons a year (about two-thirds of the entire grain production of Australia), he notes, thanks to China’s population “moving up the food chain and consuming more grain-based meat, milk, and eggs.”

By 2030, China will import almost one-third of all food available in the world, the Economist Intelligence Unit recently predicted, up from 4 per cent in 2007.

While the vision of an entire world that has become China’s factory farm is certainly terrifying, the reality up until now has been a lot less scary. At least so far, China’s increased appetite for imported foods appears to have helped local economies, without starving local populations or causing widespread environmental degradation.

China’s recent embrace of olive oil, for example, was a welcome change for Mediterranean nations, where olive oil prices plummeted in 2012 because of the weak EU economy and a bumper Spanish crop. Because China does not grow any olive oil of its own, imports have tripled between 2009 and 2013 to 43,000 metric tons, which helped support global olive oil prices last year. China’s consumption is still relatively small, particularly when viewed next to the world’s largest food importing country, the US. China imported just 14% of the 290,000 metric tons of olive oil the US imported in 2013.