More public funding is not the answer to the troubles of Italian opera

Italy’s opera theaters are in deep trouble: as the Wall Street Journal recently reported, government austerity has reduced their budgets, and by the end of the year the houses whose balance sheets aren’t in order won’t be able to apply for public funding at all.

Italy’s opera theaters are in deep trouble: as the Wall Street Journal recently reported, government austerity has reduced their budgets, and by the end of the year the houses whose balance sheets aren’t in order won’t be able to apply for public funding at all.

Opera in Italy depends heavily on the state’s support: public contributions make up an estimated 41% of the budget at the famed La Scala, and that’s the Italian opera house that relies least on public funds. At some of the ”enti lirici” (opera foundations), as Italy’s 14 recognized opera houses are known, public funding provides up to 88% of the total.

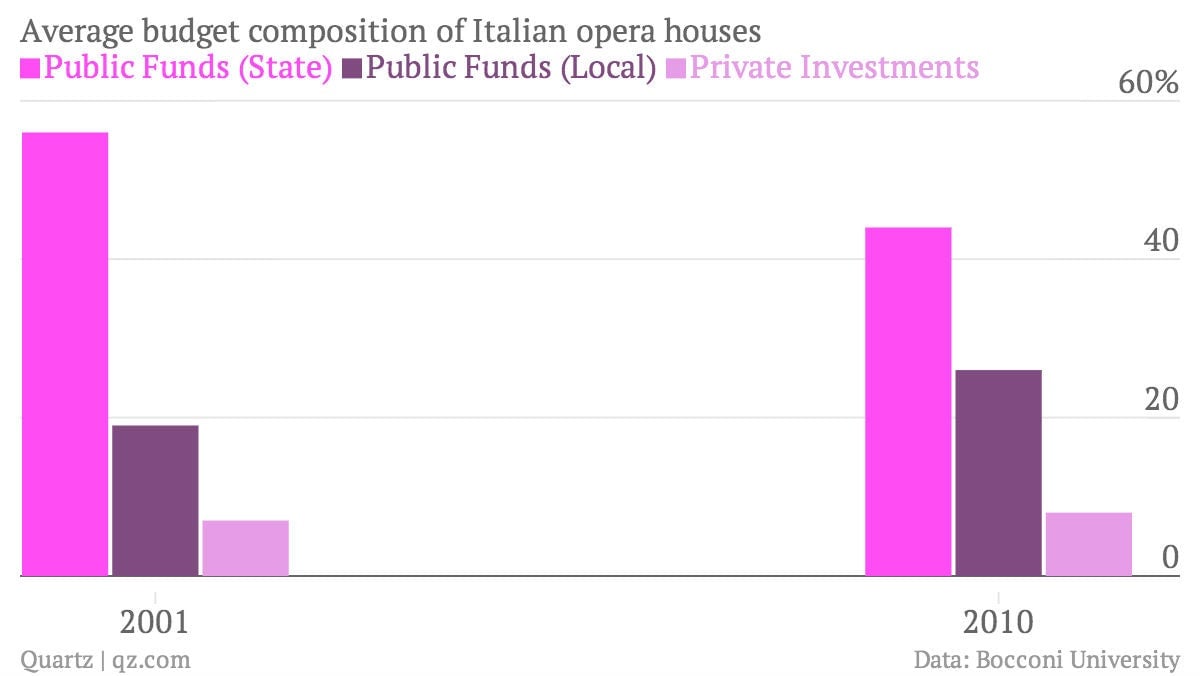

Italy’s opera theaters have been relying progressively less on public funds due to cuts since the recession, but private funds have failed to fill the gap. From 2001 to 2010, private investment has only risen from 7% to 8%, according to data collected by Bocconi University. One problem is that donating to such institutions doesn’t offer many tax advantages, compared to countries such as the United States, where most of the budget of New York’s Metropolitan Opera is made up of tax-deductible private donations.

But there is another cultural reason at play: Opera is part of Italy’s heritage, and there is a common belief that it is a duty of the Italian state to finance it.

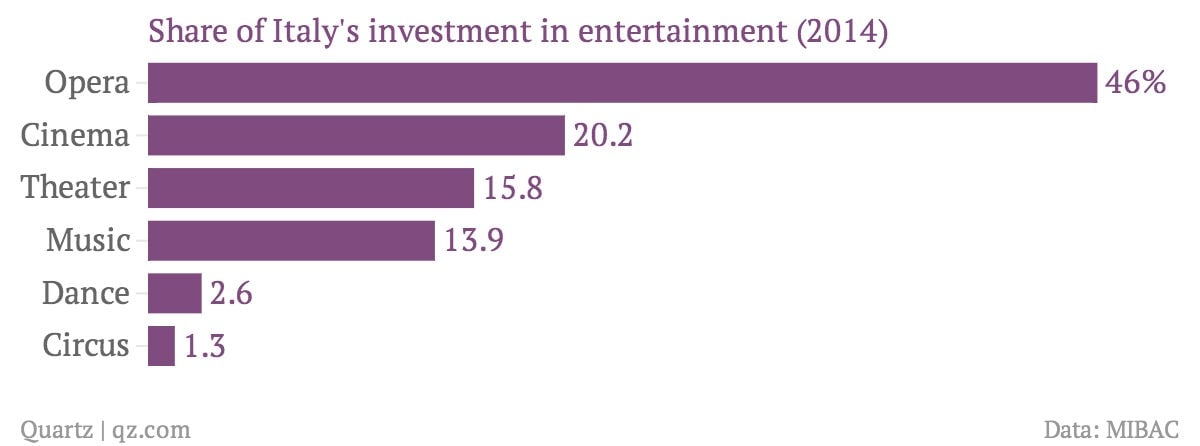

And the Italian state does indeed invest a copious amount of money to help opera survive—the sector hogs about half of all the money that the government invests in entertainment.

Italy’s investment in entertainment actually increased this year—€406 million (about $550 million), compared to €380 million in 2013—but it still hasn’t rebounded to pre-recession levels, and isn’t enough to compensate the massive losses opera houses have accumulated through the years.

And state opera subsidies are still quite generous when you consider that taxpayers’ money goes to support a form of entertainment that remains prohibitively expensive for most Italians: The most affordable (decent) tickets to go see Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata (the world’s most-staged opera) at Teatro alla Scala in Milan sell for €350, or over a fourth of the net average monthly income in Italy.

Some of the opera’s problems are architectural: Italy’s theaters are some of the world’s most beautiful and oldest (Teatro San Carlo, in Naples, has been open since 1737), so they have have high maintenance costs and storage problems. They are mostly only big enough to store one set, making it impossible to stage different operas at the same time. But the main problem is that opera houses haven’t cut their running and personnel costs, and have instead tried to save money by staging fewer operas, limiting their earnings from ticket sales.

One possible silver lining to the funding crunch is that it could help Italian opera houses reform their finances, from leaner operations to changes in the tax law that would encourage private donations. While such changes won’t fundamentally transform the nature of an entertainment that’s expensive for producers and audiences alike, it may offer a better shot at keeping the art form alive—even if it remains in a perpetually agonized state that some of Verdi’s tragic heroines might recognize.