Hong Kong protesters blame China for rising inequality and economic woes

Thousands of Hong Kong residents are marching today to protest Beijing’s tightening grip on the semi-autonomous city—a demonstration that organizers say should be the city’s largest in a decade. China’s influence over local media and politics are among the main issues fueling discontent, but there is also a growing sense of anger at the economic changes that have transformed Hong Kong in the 17 years since it returned to Chinese control, especially the idea that wealth inequality and economic opportunity have taken a dramatic turn for the worse.

Thousands of Hong Kong residents are marching today to protest Beijing’s tightening grip on the semi-autonomous city—a demonstration that organizers say should be the city’s largest in a decade. China’s influence over local media and politics are among the main issues fueling discontent, but there is also a growing sense of anger at the economic changes that have transformed Hong Kong in the 17 years since it returned to Chinese control, especially the idea that wealth inequality and economic opportunity have taken a dramatic turn for the worse.

“What makes us worry is that the Hong Kong we are living in today is not the Hong Kong we knew,” Carol Luk, 31, who works for a bank in Hong Kong and is volunteering with a group called Occupy Central, told Quartz. Luk and her friends worry about job prospects and their ability to buy a home when property prices have been pushed up by wealthy mainlanders, some of the reasons why she has decided to demonstrate on the handover anniversary.

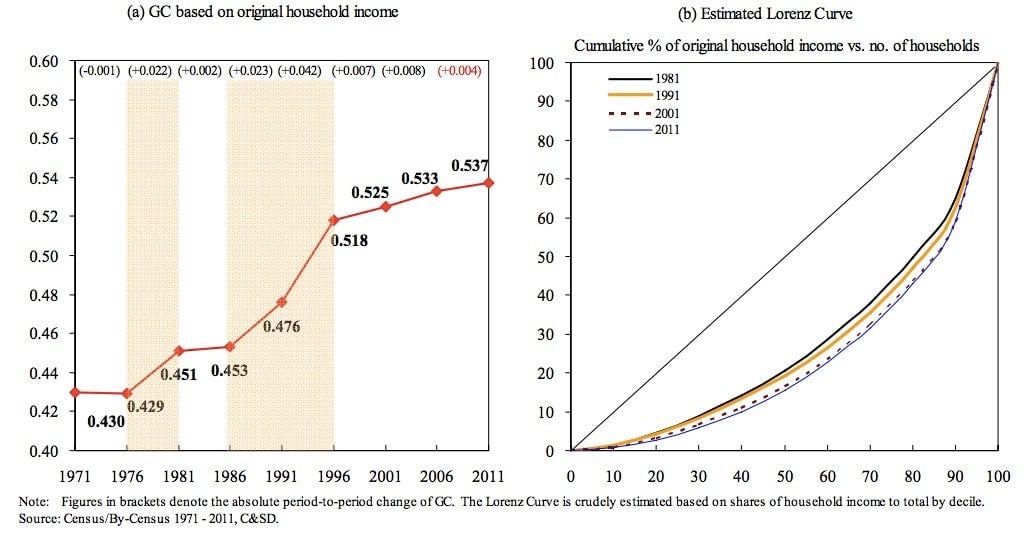

In the 1970s, the early days of Hong Kong’s break-neck industrialization that made it one of the “four Asian tigers,” inequality was relatively low. The city’s gini coefficient, a commonly used indicator where 0 represents total equality in a society and 1 represents complete inequality, was around 0.430. In the 1980s, as Hong Kong began to reintegrate with the liberalizing Chinese economy, that figure started to tick upwards, spiking especially around the time of the 1997 handover.

The rate of increase has leveled off since then, but at 0.537 Hong Kong’s gini coefficient today is among the the highest in East Asia, and higher than that of the UK, Singapore, Australia, or the United States.

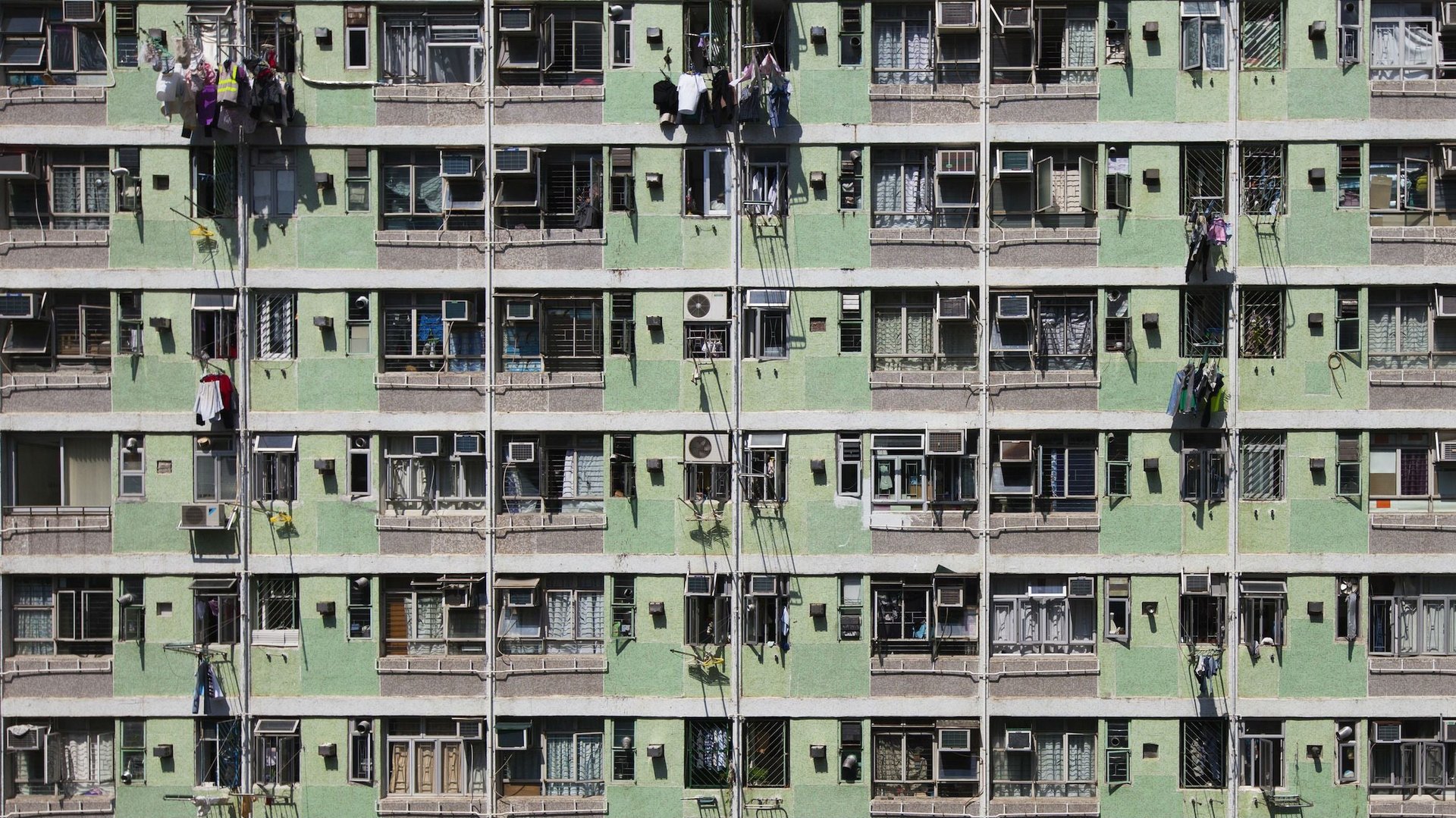

Today, some 2 million people, or 30% of the population, live in public housing estates, and one fifth of the population lives below the poverty line. Those who can’t wait for the overcrowded public housing system live in neighborhoods like Sham Shui Po, infamous for its “cage homes“— cheap, small metal cubicles consisting of a bunk bed and not much else.

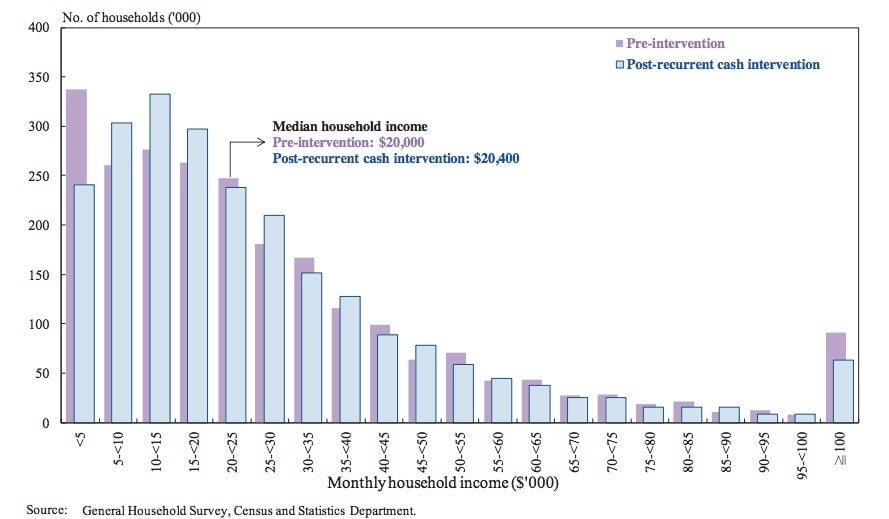

And the depth of poverty in Hong Kong appears to be getting worse. According to the government, the poverty gap—the amount of money theoretically needed to pull families back to the poverty line—widened to $28.8 billion (pdf, p. 24) in 2012 from $25.4 billion in 2009.

“It’s not like the ’70s and ’80s, where we know our salary is going up or next year or we’ll get a promotion,” says Li Kui-Wai, an associate professor of economics at the City University of Hong Kong. “Our economy is not as good as used to be.”

Protesters calling for the universal suffrage that Beijing promised the city by 2017 see a direct link between income inequality and political freedom. Today, Hong Kong’s chief executive is elected from a list of Beijing-approved candidates.

Chief executive Leung Chun-ying promised to deal with inequality when he came to office in 2012, but protesters and other critics say he has been too beholden to Beijing to pursue effective policies. His popularity is at an all-time low. “The government just isn’t attentive to the matter, and one of the big reasons is that it is not elected by the people,” says Brian Kern, an American who has lived in Hong Kong for six years and is participating in the protests.

Economists and the Hong Kong government dispute whether China can be directly blamed for the city’s economic troubles. The government attributes Hong Kong’s growing inequality to immigration of low-skilled workers into the city and an aging population that widens the base of economically inactive or low-paid residents. Unemployment has stayed steadily low, at 3.1%, the lowest rate since the late 1990s. Moreover, Hong Kong’s trade and services sector depends heavily on mainland China.

But the perception of economic injustice isn’t helped by the fact that every day wealthy mainland Chinese pour into the city to do their luxury shopping, empty local stocks of infant formula, and give birth to their children here so that they can have Hong Kong residency. A new proposal to develop an area in northern Hong Kong known as the New Territories into luxury and retail space catering to wealthy mainlanders, which would displace over 6,000 farmers and villagers, is also exacerbating tensions.

This is especially the case among students and young people demonstrating against the government. According to a poll released yesterday by Hong Kong University, the younger a respondent was, the more critical they were of Beijing’s policies toward Hong Kong and the less likely the were to feel proud of becoming a Chinese national.

“They are more sensitive to this great division of wealth,” Joseph Wong Wing-ping, a former senior public servant in Hong Kong, told the New York Times. “The society is changing, and you have more and more of this discontented, active, sometimes assertive civil society led by the younger generation.”

By the afternoon, protesters had gathered at Hong Kong’s Victoria Park with banners, chanting and occasionally breaking into refrains of the song, “Do You Hear The People Sing.” Some protesters burned a portrait of chief executive Leung. Organizers expect as many as 500,000 protesters; already 4,000 police have been dispatched.

Luk said, “Hong Kongers are very pragmatic. If there’s a high turnout it means the silent majority has come out.”