The genius of building a maze at a city’s center

I’m the kind of person who probably couldn’t find his way out of a paper bag, so it was with some hesitation that I stepped into the BIG Maze. This is a project at Washington DC’s National Building Museum, a summer folly designed by the always-entertaining Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group, a plywood playground where kids will snap selfies all season long. For a person with a sense of direction like mine, though, it couldn’t be worse if a Minotaur were lurking in the middle.

I’m the kind of person who probably couldn’t find his way out of a paper bag, so it was with some hesitation that I stepped into the BIG Maze. This is a project at Washington DC’s National Building Museum, a summer folly designed by the always-entertaining Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group, a plywood playground where kids will snap selfies all season long. For a person with a sense of direction like mine, though, it couldn’t be worse if a Minotaur were lurking in the middle.

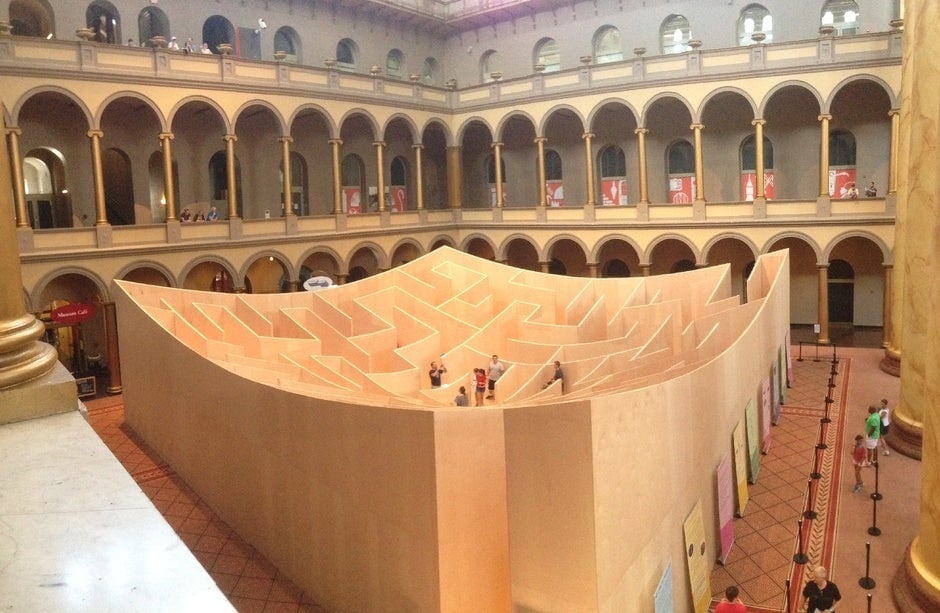

The labyrinth swallowed me. Though the structure is dwarfed by the cavernous museum itself, this maze is no slouch, spanning more than 3,000 square feet. In a word, it’s big: The maple-wood walls rise 18 feet high, and each side is is 57 feet long. Welp, I thought, as I assessed my inventory: If I was going to have to live in a maze for the holiday weekend, at least I had a Perrier.

Touring the maze’s multiple dead ends gets a little easier, ostensibly, as you proceed through and notice that the walls slope down toward the center. From there, you can get a sense of the maze’s plan, a helpful feature for a person with spatial-reasoning skills. Again, that’s not me. Fortunately, I overheard a couple mention they’d already been through twice, so I just followed them around until we all made it out. Chalk it up as a supposedly fun thing I’ll never do again. (Though less panicked folks did seem to enjoy it!)

It shouldn’t come as any surprise that Bjarke Ingels would respond to an invitation from the National Building Museum with a design for a maze. The architect is known for his whimsy. When Copenhagen decided on building a waste incinerator in the city, the city turned to Ingels to create a design that would make the facility more palatable to residents; he designed the Amagerforbraending waste incinerator as a functional ski slope, one that emits exhaust (essentially water vapor) in periodic, puffy smoke rings. For another Copenhagen project, the Superkilen urban park, Bjarke Ingels Group imported signage, structures, and public design objects from all over the world, making it a sort of global, comical fair ground.

Bjarke Ingels Group is one of the fastest-rising architecture firms in the world: Last year, the Smithsonian Institution tapped BIG to design its new master plan, effectively giving it say over the shape of the National Mall. It’s also a firm with a decidedly urban footprint—as the BIG Maze shows.

Ingels’s native Denmark is home to the world’s largest maze, the Samsø Labyrinten, a 646,000-square-foot hedge maze and a place that I will never visit. If it was an influence on the BIG design, it doesn’t show. The BIG Maze demonstrates that even a convincing labyrinth, a structure that by its very nature seems to call for sprawl, can be scaled to fit a dense urban model.

Now, once you’re lost inside it, it might seem perfectly reasonable that a large, disorienting maze should fit on a museum floor. You know, the same way that Copenhageners appear to have taken to the idea that a ski slope should be built inside their city center. Neither of these outcomes is too obvious from the outside, though. So even a maze skeptic like myself—fine, I’m just outright afraid of them—can see the genius of actually building something like this.

There’s a skill to seeing a space not as it is, but as what it could be. Building mazes is a sort of fun, low-cost way to tap the potential of a space like, say, a public plaza. It’s also a great way to demonstrate local architectural talent, native building materials, and sheer engineering ingenuity. Cities could compete with public mazes the same way counties do with fairs. Plus, you could do worse when it comes to free entertainment for kids—mazes are the ultimate babysitters.

Bjarke Ingels takes a “sure, why not?” approach to his work: The firm’s first monograph is a graphic novel, for example. Build a maze inside a museum? Sure, why not? In terms of adaptive reuse and breaking up the rhythm of public space, there turn out to be compelling reasons at work here.

This post originally appeared at CityLab. More from our sister site:

London is gambling away opportunities for post-recession recovery