Lucrative Chinese product placements create a “Transformers”-sized headache

Chinese companies who paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to have their brands featured in the latest Transformers movie, Age of Extinction, are complaining about the lackluster product placements, and at least one is suing Paramount Pictures, the US studio that co-produced the film.

Chinese companies who paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to have their brands featured in the latest Transformers movie, Age of Extinction, are complaining about the lackluster product placements, and at least one is suing Paramount Pictures, the US studio that co-produced the film.

The troubles facing the makers of Age of Extinction are a sign that one of the main sources of cinematic funding from China may not be the easy source of money that studios had hoped for—even for a movie that is on course to become China’s highest grossing film.

The Chongqing Wulong Karst Tourism company has said that it will file a lawsuit against Paramount for not showing its logo in the film as stipulated by its contract. (Paramount counters that the company did not submit its payments on time.) A Chinese takeaway chain that sells duck necks said it was ”very dissatisfied” with a three-second shot of its meat in a refrigerator. And a Beijing luxury hotel, Pangu Plaza, was unhappy that it was only featured for a few seconds and threatened its own lawsuit—until Paramount rushed over a replica of the Transformer character known as Bumblebee and arranged a last-minute premier.

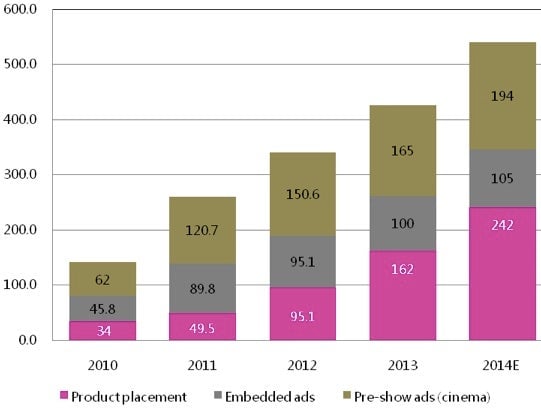

Hollywood film studios have been turning to China, which is home not only to the world’s second-largest box office market but one of the world’s fastest growing markets for product placement advertising, according to media research firm PQ Media. Product placements in domestic movies can subsidize as much as 30% of a film’s budget. Revenues from brands have more than quadrupled since 2010 and are expected to reach $242 million this year, according Connect China, a research consultancy.

According to an unofficial count by viewers, Age of Extinction, a co-production between Chinese and American film studios, featured no fewer than 10 Chinese brands, ranging from Yili Milk to Lenovo computers. By comparison, domestic movies in China had an average of about 4 brands per film in 2013, according Connect China.

What went wrong? The deals with Pangu Plaza and Wulong were made through third-party Chinese agencies, complicating communication channels and leaving much to be lost in translation. In the case of Wulong, the US production team thought that a sign that read ”Green Dragon Bridge” was actually the nature park’s logo. (Paramount was not immediately available for comment.)

In the end, it’s not clear that Chinese product placement in Hollywood films has its intended impact—to make brands more appealing to Chinese shoppers. Mainland movie-goers complained the placements were awkward: in the middle of a Texas desert, a character sips on a Chinese energy drink virtually unknown in the US, in another scene, an American character pulls out a Chinese bank’s debit card. One viewer wrote on Weibo (registration required) after seeing the film, “It’s disgusting to see so many ads in one movie.”

Cathy Yi Sizhao contributed additional reporting.