George Lucas’s best idea since Star Wars: A museum of narrative art

An art museum is supposed to spark discussion about the artists whose works are collected inside—not about the person whose name is on the building.

An art museum is supposed to spark discussion about the artists whose works are collected inside—not about the person whose name is on the building.

But the recently announced Lucas Museum for Narrative Art, director George Lucas’s testament to the power of visual narrative, will likely do both when it opens in Chicago in 2018. That’s because unlike a lot of museums—including its lakefront neighbors the Field Museum, the Shedd Aquarium, and the Adler Planetarium—the guy who gives the museum its name will also give it start-up money and a number of his own projects for immediate display. It’s a radical move. Hollywood directors, producers, and actors regularly dabble in all aspects of the movie business, but in the art scene, curators and philanthropists take care to stick to their prescribed roles.

Not everyone’s excited to see a blockbuster director ignore the museum world’s traditional divide between art and commerce. History has seen very few high-profile hybrid creator/curators. There were exceptions, of course, but when Auguste Rodin established his Musée in 1919, he boasted serious art-world credentials. Criticizing Lucas, Deanna Isaacs argued in the Chicago Reader that 20th-century merchandising magnates Marshall Field, John G. Shedd, and Max Adler promoted a higher standard of museum by resisting the urge to, say, exhibit Sears-Roebeck catalogs and Frango mints. “Discreet, anonymous philanthropy is a distant memory of a less crass era,” she lamented. Other have called the Lucas Museum a “vanity project,” the same title offered to explain the director’s poorly reviewed Star Wars prequels and animated series.

In truth, though, the museum may be Lucas’s best original idea since A New Hope. Lucas proposes an institution that—like his culture-hopping, historically inspired films—connects the visual storytelling techniques of antiquity (cave art, illustrations) to the those of the modern day (animation, digital art), for a time-bending, medium-defying, cross-platform experience. If the premise appears self-serving, it is also the logical culmination of a few art-world trends old and new.

“Vanity projects” are nothing new in America, where the arts are driven primarily by private, not public, funds. Old-school, philanthropic museums of the kind Isaacs praises were themselves public monuments to their founders’ savvy. They were also, as MIT professor Peter Temin writes in The Economics of Art Museums, a tastemaking project by nouveau riche American tycoons: When the Industrial Revolution triggered fears that the growing immigrant workforce would prevent America from developing a highbrow culture like Europe’s, the wealthy fought the perceived onslaught by funding institutes filled with old-world classics “to educate the people’s taste, to help them identify with the values of the successful industrialists.”

Today’s benefactors, though, buy and preserve what they consider purely American art. According to Anne Higonnet, a Columbia University and Barnard College art history professor and the author of A Museum of One’s Own: Private Collecting, Public Gift, private collectors in the past few decades have been stealthily accumulating valuable holdings in order to tell their versions of the country’s art history. “Each in their own way these museums are making a bid to define what art is in America and what it has been in the 150 years,” she told me.

There’s a fittingly egalitarian spirit to this latest wave of museum openings. Higonnet pointed to the Rubell Family Collection founded by the famous hotelier family, which opened shop in a former DEA facility in Miami’s rundown Wynwood neighborhood to display the kind of avant-garde works usually found in high-end art galleries. Perhaps even more daring is Crystal Bridges, Walmart heiress Alice Walton’s passion project that brought Lichtenstein and Warhol to a small town in the Ozarks. Costing a reported $1.2 billion to open in 2011, Crystal Bridges doesn’t charge for admission, a fact that, as Roberta Smith wrote in her New York Times review, “convey[s] the belief that art, like music and literature, is not a recreational luxury or the purview of the rich. Rather, it is an essential tool… [that] helps awaken and direct the individual talent whose development is essential to society, especially a democratic one.”

Lucas, too, is trying to popularize American art history—but by using the lessons he’s learned in the movie business. According to the bits and pieces in his proposal and his museum website, he will sponsor an “experience” emphasizing that art has told stories ever since the earliest hieroglyphs and cave paintings. The exhibitions will follow “narrative art” through the technological advancements of the 20th century and into the “digital mediums of the future,” all of which makes narrative sound like it’s on its way to becoming the dominant art form in this country, if it hasn’t achieved that status already.

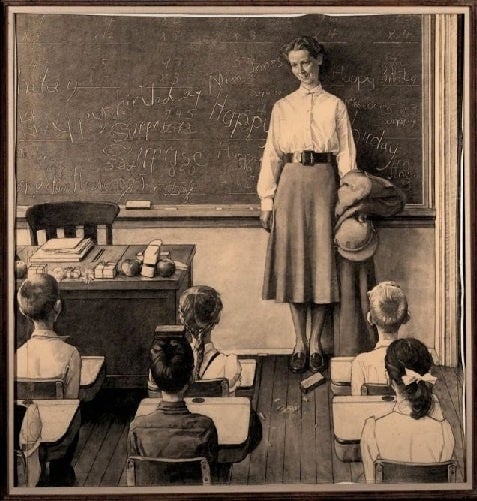

Lucas’s alternative timeline may sound like an all-too-convenient art history lesson from a blockbuster Hollywood director. But the rest of the art world increasingly shares his interest in no-brow, representational art. Twentieth-century illustration is a hot bid at the moment, with prices for Norman Rockwell pieces reaching new heights at Christie’s in May (the illustration in question, “The Rookie,” is a portrait of a recruit’s first encounter with the Boston Red Sox locker room). Several young American institutions that exhibit 20th-century storytelling art have grown more popular in recent years, according to Higonnet. They include the Brandywine Museum of Art, which houses a collection of illustrators and cartoon artists from Howard Pyle to Maxfield Parrish and a particular concentration with the Wyeth family, and the Norman Rockwell Museum, which has expanded its purview to include all of American illustration.

As for the still-under-wraps contents of Lucas’s personal collection, we can expect the splashiest 20th century pieces of this kind that Star Wars proceeds can buy. Laurie Norton Moffatt, director of the Norman Rockwell Museum, is among the few curators who’ve glimpsed the art that hangs in Skywalker Ranch. She says it is “superb” and contains some “truly magnificent works.” The project’s PR director David Perry values the full contents anywhere from “$600 million to priceless.”

Of course, it took nearly 50 years for Rockwell to accumulate the value he enjoys today. The boldest move Lucas makes is to launch the slow-moving curatorial process into hyperspace and extend the same reverence to modern visual storytellers who are at work now. Of the 17 pieces have been released so far, five are animations and production designs for commercial films—work the art world considers lowbrow, and Hollywood mere hackwork. Just as A New Hope combined tony inspirations from The Searchers and Casablanca with obscure nods to Akira Kurosawa, the old parts of Lucas’s collection seem devised to ease the audience into the newer and edgier stuff.

As when the MoMA raised a stir in 2012 by introducing 12 video games into its permanent collection, effectively allowing little kids to play Pac-Man while their moms checked out the Rothkos, Lucas has tapped into a preexisting entertainment market. Imagine what the moms will say when their kids spend their educational museum jaunt watching CGI from Rango and Terminators 3: Rise of the Machines. And imagine how much the kids might actually enjoy the visit.

Like his philanthropist predecessors, Lucas intends to shape our understanding of American art; the difference is that he respects our enjoyment of it, too. A crass Hollywood sensibility this most certainly is, but also one that is more attuned to how the public likes to take its cultural enrichment. Preferably with a story, some recognizable characters, and postproduction magic. “He’s the Jedi knight of narrative art,” Higonnet told me, “and this museum is his big art-history lightsaber.”