Another US drug company tries to flip itself into low-tax territory

Another day, another mega-merger designed to pull a pharmaceutical company out of reach of the US tax man.

Another day, another mega-merger designed to pull a pharmaceutical company out of reach of the US tax man.

AbbVie, the US maker of arthritis treatment Humira, has put a $53-billion (£31-billion) offer up for Shire, the Dublin-based producer of Vyvanse, used to ameliorate attention deficit disorder. Should the deal go through—this is AbbVie’s fifth attempt—the combined company would move its headquarters to the United Kingdom to take advantage of low taxes and avoid the higher statutory corporate rate in the United States.

These “inversions” are becoming an increasingly popular tactic for pharma companies, thanks to the ease with which they can move their primary assets—people and intellectual property—around the world. Financial engineering is typically a quicker path to an earnings boost than the multi-year process of developing and marketing new drugs.

But the cut-and-run strategy has raised hackles in the US, not just because of the lost tax revenue (which leaves other companies and Americans to make up the shortfall), but also because of the loss of politically influential pharmaceutical companies, which can reap numerous public benefits, including putting the US government to work to protect high drug prices around the world.

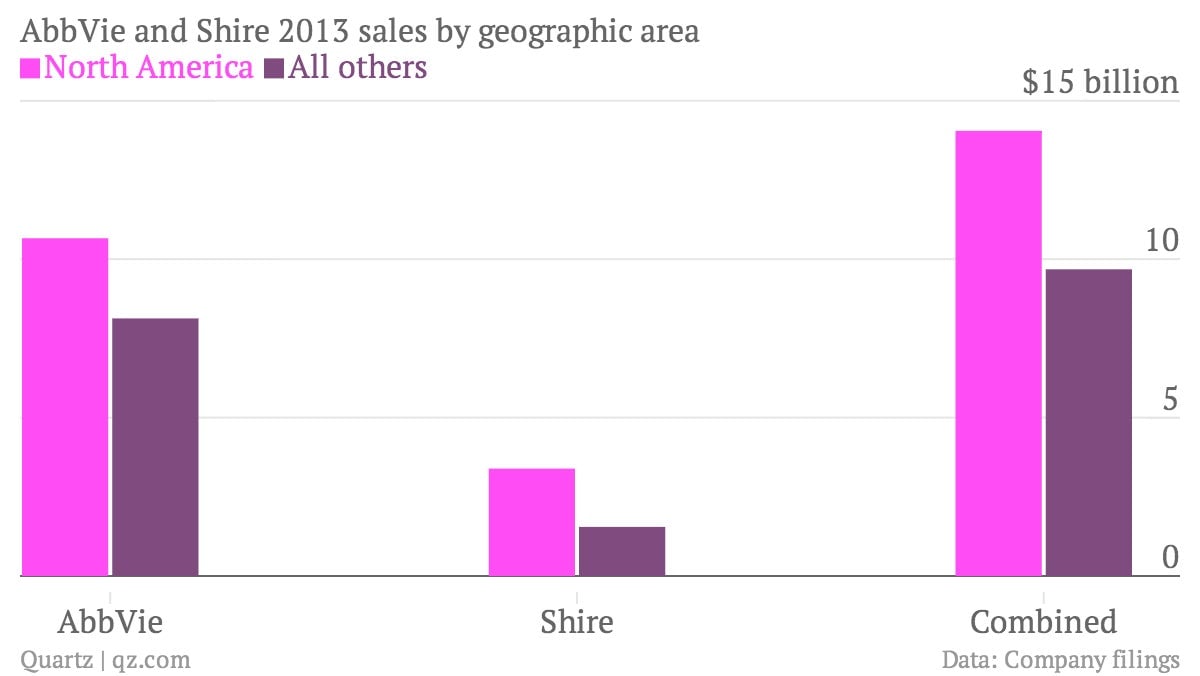

One thing is for certain: The location of the two companies’ customer base shows little business justification for the moves.

But the validity of these inversions is not judged based on sales. Under US law, which does not take into account where a firm’s management is located, a company needs only to have 20% or more of its equity owned by foreign investors to move its headquarters abroad. While some lawmakers are pushing to lift that standard to 50% of equity, there is little indication that such a measure will pass swiftly enough to prevent this deal or many others like it.