Read Netflix’s plea to ban paid “fast lanes” on the internet

Netflix ripped into Comcast, Verizon, and other internet providers in a lengthy document submitted to the US government today.

Netflix ripped into Comcast, Verizon, and other internet providers in a lengthy document submitted to the US government today.

The key issue is whether internet providers should be able to charge content companies such as Netflix for a more direct route to customers. Netflix and other net neutrality advocates argue that these paid “fast lanes,” give providers too much control. Internet service providers (ISPs) argue that charging companies such as Netflix helps relieve congestion on the broader internet and gives customers a better experience.

“There can be no doubt that Verizon owns and controls the interconnections that mediate how fast Netflix servers respond to a Verizon Internet access consumer’s request,” Netflix writes in the 28-page document, which is part of the company’s official comments to the US Federal Communications Commission on new net neutrality regulations. (Comcast filed its own comments (pdf) with the FCC yesterday.)

Here are the highlights:

The Virtuous Circle: Openness Supports the Internet’s Growth

III. The FCC Should Not Codify Fast and Slow Lanes on the Internet

A. Paid Prioritization Is Bad Public Policy

Interconnection Between Networks Is Critical to Internet Openness

The Internet is improving lives everywhere—democratizing access to ideas, services, and goods. The Internet has grown into the amazing medium it is today largely because information is received by the person requesting it efficiently, unimpeded by gatekeepers. In other words, “the Internet’s remarkable ability to generate innovation, investment, and economic growth is a product of its openness.” Furthermore, the cooperative relationship between broadband networks and the information and services they carry drives improvements both among network operators and edge service providers.

This “virtuous circle” creates opportunities for greater and richer applications that in turn drive consumer demand for better and faster broadband connectivity. Absent protections to preserve an open Internet, this virtuous circle—and much of the innovation and economic growth it has created to date—is threatened. Unfortunately, the Commission’s proposal does little to protect the open Internet. In fact, by endorsing the concept of paid prioritization, as well as ambiguous enforcement standards and processes, the Commission’s proposed rules arguably turn the objective of Internet openness on its head—allowing the Internet to look more like a closed platform, such as a cable television service, rather than an open and innovative platform driven by the virtuous circle.

The Commission has previously concluded that paid prioritization “would represent a significant departure from historical and current practice” that “could cause great harm to innovation and investment in and on the Internet.”6 Netflix agrees. Yet, the Commission’s NPRM would for the first time since the beginning of the commercial Internet authorize an ISP to charge content providers for prioritized access to consumers. In essence, the Commission’s proposed rule would codify discrimination on the Internet.

Chairman Wheeler has pledged to “prevent the kind of paid prioritization that could result in ‘fast lanes,’” but as a legal matter this pledge is irreconcilable with the text and terms of the proposal advanced in the NPRM. This contradiction is driven by the Commission’s underlying legal theory in support of the proposed rules, which looks to authority solely under Section 706.8 Unfortunately, in doing so, the Commission must water down and even reverse the protections and presumptions of openness that have characterized the Internet since its inception. So despite good intentions, the Commission apparently believes that a bad rule is better than no rule. Netflix disagrees. No rule is better than a bad or ineffectual rule.

The Internet today functions as a competitive equalizer because all edge providers enjoy the same ability to reach end users over last-mile networks. Through an open Internet, the consumer, not the ISP or the edge provider, picks the winners and the losers. Prioritization turns this successful model on its head, effectively allowing ISPs to choose what their subscribers see and do on the Internet and from whom they get their content.

In a pay-for-priority model, the ISP’s subscribers likely will face less choice and diversity in edge provider services (at higher cost) while receiving poorer service from their ISP. Rather than incentivizing edge providers to offer more and diverse services, paid prioritization would raise barriers to entry, lessen competition and innovation, and impose needless transaction costs. A pay-for-priority Internet also inflicts unique harms on noncommercial end users, particularly those that choose to communicate their ideas or opinions “through video or other content sensitive to network congestion.” Pay-for-priority also would enable terminating ISPs to increase costs for online rivals or degradetheir services.

Furthermore, pay-for-priority arrangements undermine an ISP’s incentive to continue building capacity into its network. Prioritization has value only in a congested network. After all, there can be no “prioritization” in an uncongested, best-efforts network; all packets necessarily move at the same speed. As the Commission has acknowledged, this creates a perverse incentive for ISPs to forego network upgrades in order to give prioritization value.

[…]

It is called the Inter-net for a reason. That is, the Inter-net comprises interconnections between many autonomous networks, all sharing common protocols. As the Commission already understands, effective rules must “ensure that a broadband service provider would not be able to evade our Internet rules by engaging in traffic exchange practices that would be outside the scope of the rules.” Open Internet protections that guard only against pay-for-play and pay-for-priority on the last mile can be easily circumvented by moving the discrimination upstream. As such, for any open Internet protection to be complete, it should address the points of interconnection to terminating ISPs’ networks.

Some ISPs have argued erroneously that any congestion occurring at the point of interconnection is out of their control and that edge providers are solely responsible for any problems they have accessing the terminating ISP’s network. ISPs, not online content providers, set the universe of available pathways into their network. Applications and services cannot utilize any route into the network unless it is “advertised” by an ISP. What’s more, the availability, terms, and quality of interconnection to that network are controlled and set by the terminating ISP. So, when an ISP like Verizon fails to upgrade interconnection points to its network, Netflix data enters the network at a drip-like pace, and consumers get a degraded experience despite already paying Verizon for more than enough bandwidth to enjoy high-quality online video services. There can be no doubt that Verizon owns and controls the interconnections that mediate how fast Netflix servers respond to a Verizon Internet access consumer’s request.

Putting in last-mile protections while leaving interconnection exposed to abusewill do nothing about congestion at the entrance to a terminating ISP’s network. Instead, it will create a perverse incentive for the ISP to leave interconnection points congested, even in the face of growing data requests from its customers, in order to try to extract fees from online content providers to buy their way out of congestion.

Discrimination and unfair access charges at interconnection points are not theoretical. Their effects on consumers have been picked-up in the popular press.23 As the Commission is aware, Netflix and its members have been impacted by interconnection congestion, particularly on Comcast’s and Verizon’s networks.

The Comcast situation provides a case study in how an ISP can use its terminating access monopoly to harm edge providers, its own customers, and the virtuous circle by discriminating at interconnection and peering points. The amount of video content traffic requested by Comcast’s broadband subscribers has increased significantly over time. In 2012, Netflix realized that the interconnection traffic created by the data requests from ISP customers for Netflix content was rising faster than many ISPs were increasing their interconnection capacity. In an effort to limit any negative impacts from the increased traffic, Netflix offered to deploy for free its Open Connect platform24 on Comcast’s network, but Comcast refused.

Instead, Comcast allowed every port carrying Netflix data to become congested by refusing to make routine upgrades to those interconnection points. One transit provider even offered to send for free the equipment Comcast would need to mitigate the congestion. Again Comcast refused.

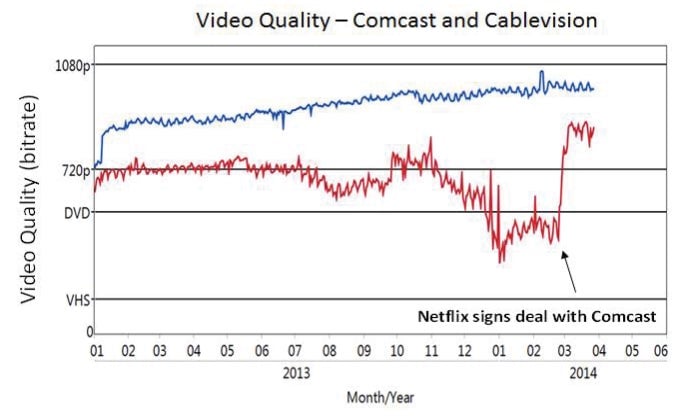

During this period, the harm to Comcast’s and Netflix’s mutual customers was significant. Comcast subscribers went from being able to view Netflix content, on average, at 720p (i.e., HD quality) to nearly VHS quality. Many Comcast subscribers experienced bit rates that were even lower—so low that they were either unable to view content all together or at least not without constant, annoying rebuffering. This scenario contrasts with data regarding Cablevision’s customers. Cablevision incorporated Open Connect, which resulted in its subscribers experiencing video quality approaching 1080p during the same period as Comcast’s customers were experiencing VHS quality video or worse.

Comcast chose to engage in its congestion strategy, even though it knew that it would be significantly deteriorating the online experience of its own subscribers. While it had promised its customers “blazing fast” Internet speeds, Comcast simultaneously was preventing those customers from receiving their content at the speeds Comcast had promised. Comcast customers experienced this degraded network performance regardless of the service tier they purchased. Comcast customers paying for a broadband Internet access connection of 25 Mbps were, during the worst of the congestion, getting Netflix content at less than 1 Mbps, and often less than that. But Comcast customers paying significantly more for a 105 Mbps connection fared no better. Due to Comcast’s degrading its interconnection points, the first customer received less than 6% of the broadband service she had purchased from Comcast, while the second received only 1%.

Even in the face of significant negative news reports over its congestion strategy, Comcast was willing to let congested network conditions persist. Comcast would not address the problems its customers experienced until Netflix paid. Once Netflix paid, Comcast immediately rectified the congestion problem. As the above graph demonstrates, Comcast effectively doubled its capacity at the congested interconnection points within 8-9 days.

In an attempt to foreclose criticism of its interconnection practices, Comcast has claimed that there are myriad ways into its network. But the number of transit providers or pathways into Comcast’s network is irrelevant to this issue. Indeed, prior to its agreement to interconnect directly with Comcast, Netflix purchased all available transit capacity into Comcast’s networks from multiple large transit providers. Every single one of those transit links to Comcast was congested (even though the transit providers requested extra capacity). All other routes into Comcast’s network were subject to access charges, in addition to the transit fees Netflix was already paying. Such a situation highlights that every transit provider must ultimately negotiate with Comcast for a connection to Comcast’s network, and Comcast controls the terms of that access. Simply put, there is still one and only one way to reach Comcast’s subscribers: through Comcast. Again, it is within the context of this market dynamic that the Commission must consider its open Internet rules.

Comcast also has attempted to confuse the matter by suggesting that Netflix’s payments to Comcast have allowed Netflix to cut out the “transit middleman” and save costs. But for edge providers such as Netflix, paying a terminating ISP like Comcast for interconnection is not the same as paying for Internet transit. Transit networks like Level 3, XO, Cogent, and Tata perform two important services: (1) they carry traffic over long distances; and (2) they provide access to every network on the global Internet. Comcast does not connect Netflix to other networks. Nor does Comcast carry Netflix traffic over long distances. Netflix is itself bearing the costs and performing the transport function. It is Netflix that incurs the cost of moving Netflix content long distances, closer to the consumer, not Comcast.

Comcast and other ISPs have even gone so far as to suggest that Netflix is “freeriding” by unilaterally “dumping as much volume” as it wants onto their networks. Netflix does not “dump” data; it satisfies requests made by ISP customers who pay ISPs a lot of money for high-speed Internet access, precisely so that they can access data-rich media like streaming video. Netflix does not send any data unless members request a movie or TV show. ISPs also argue that Netflix should help cover their network costs because Netflix members account for about 30% of peak residential Internet traffic. But online applications and services like Netflix are why consumers purchase broadband access services in the first place. If ISPs want online applications to share their costs, perhaps they should also be willing to share their revenues.

Netflix is not a free rider. Netflix does not pay Comcast for transit. Nor does Netflix pay Comcast for priority treatment of its traffic. In effect, Netflix pays access fees—without which Comcast has refused to provide sufficient capacity for Netflix movies and TV shows to enter its network and to reach our mutual customers efficiently and without degradation.