Why China wants to build a railway across South America

China’s president Xi Jinping wants to build a railway across South America, Beijing’s latest major infrastructure proposal for a region that it has been drawing closer to both economically and politically.

China’s president Xi Jinping wants to build a railway across South America, Beijing’s latest major infrastructure proposal for a region that it has been drawing closer to both economically and politically.

Xi, on a tour through the region this week, suggested that China, Peru and Brazil form a work group to lay plans for a railway link between Peru’s Pacific coast to Brazil’s Atlantic coast, according to Chinese state media. Officials are expected to issue a joint statement soon.

The proposal is one of a slew of tran-South American transportation projects in the works, all of which have Chinese involvement. Last summer, China signed a memorandum of understanding with Honduras to build a railway between Amapala on the Pacific coast and the northern port city of Castilla. Colombian and Chinese officials say a rail link project connect Colombia’s Atlantic and Pacific coast is still under discussion. Other projects under consideration include several railways within Brazil, and a Chinese telecom magnate is working with Nicaragua to build a 275km-long inter-oceanic canal that would serve as an alternative to the Panama Canal.

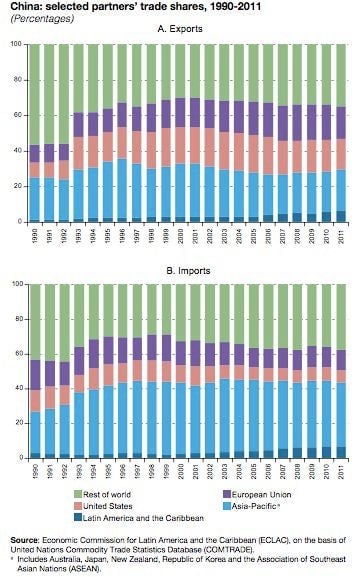

Why the push to build railways criss-crossing South America? Part of the answer—besides the fact that China knows a thing or two about constructing long railways at high altitudes—lies in the region’s burgeoning trade with China, which needs raw materials to fuel its economy and new markets for its exports. China is already Brazil’s largest trading partner. Moreover, Beijing and Lima have just signed a slew of trade deals worth $70 million.

Currently, the bulk of Chinese imports from South America have to travel through the Panama Canal, where the cost of transporting a ship through it has tripled over the last five years. Overland routes from Brazil, from whom China imports billions of dollars worth of iron ore, oil, soy and other commodities, to the Pacific could lower shipping costs.

South America’s InterOceanica, a highway that runs from Peru through the Andes and the Amazon to Brazil’s Pacific coast, was originally hailed as a way to ramp up trade with Asia. Analysts predicted it would reduce shipping costs from Brazil to Asia by possibly $100 per ton, but today the roads still aren’t equipped for heavy, long-haul shipping.

The railway can also be seen within the context of China’s larger diplomatic overtures in the region—a campaign that some say is Beijing’s attempt to wield influence in America’s backyard in response to expanding US presence in Asia. Last year, China lent $15 billion to the region, four times as much as the year before. But China’s growing ties with the region have come with tensions. Brazilians have taken to the streets to protest China’s purchase of land in Bahia state and Brazilian officials have been frustrated by Embraer’s slow progress in the Chinese market. A transcontinental railway accomplished with Chinese assistance might help resolve some of those problems.