It’s time to stop using “exoticism” as an excuse for opera’s racism

For the last two weekends, 38 white amateur performers in Seattle cinched up their obis and daubed on facepaint to perform The Mikado—standard fare for an operetta set on the fictional Japanese island Titipu where characters are given ridiculous names like Nanki-Poo and Yum-Yum.

For the last two weekends, 38 white amateur performers in Seattle cinched up their obis and daubed on facepaint to perform The Mikado—standard fare for an operetta set on the fictional Japanese island Titipu where characters are given ridiculous names like Nanki-Poo and Yum-Yum.

Decking out white actors in kimono kitsch to spoof British politics was considered witty in Victorian London. Critics in 2014 Seattle, however, have another word for it.

“It’s yellowface, in your face,” wrote Seattle Times’ Sharon Pian Chan, referring to the Asian-stereotype variation of the ”blackface” tradition where white actors dressed up as crude caricatures of African-Americans to raise laughs from other whites. Chan further condemns the production for its lack of any Asian-American performers.

And thus, the Seattle Times set off a media firestorm debating whether The Mikado is racist and should continue to be performed. The funny thing is, many more serious operas—Madame Butterfly and Turandot come to mind—do exactly the same thing. And it’s always been done that way.

This is peculiar behavior for an industry said to be ”dying.” When directors preserve cultural cliches simply because they were exotic a century ago, there’s an opportunity cost to those choices: the chance to move audiences anew. The tighter they cling to tradition for tradition’s sake, the more they rob the world’s most powerful art form of its relevance.

The Mikado

: satire or stereotype?

When The Mikado debuted in London in 1885, the sendup of British politics was an instant classic, WS Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan’s longest-running hit. The Titipu setting was key—outfitting white singers out in Meiji-era geisha-gear brought British cultural foibles into sharper focus than if the actors wore cravats and crinolines.

It’s only been in the last few decades that performances across the US have sparked protests among Asian-Americans (the operetta was taboo in Japan until a decade or so ago). While these protests, have typically been focused on the ethnic parodies, as Eric Saylor, music history professor at Drake University and co-author and editor of Blackness in Opera, points out, The Mikado‘s over-the-top japonaiserie is used to spoof only Brits, and not Japanese people.

But it’s the exoticism in these performances that is still a problem, says W. Anthony Sheppard, a music professor at Williams College. Even in productions set in, say, an English hotel in the 1930s (and starring British comedian Eric Idle), the verbal and musical Japanese flourishes remain, he says. And this points to the real source of offense: the condescension inherent when someone uses the aesthetics of another culture as ornament.

“The Mikado lampooned the Brits as much as the Japanese, but that is exactly how exoticism often works in operas, movies and literature—using an exotic setting to play out domestic desires, fears or political problems,” Sheppard told Quartz. Opera and musical theater ”have long served to teach audiences about exotic peoples and places, often providing a very persuasive and powerful form of miseducation.”

Opera’s long-standing love affair with ethnic exoticism

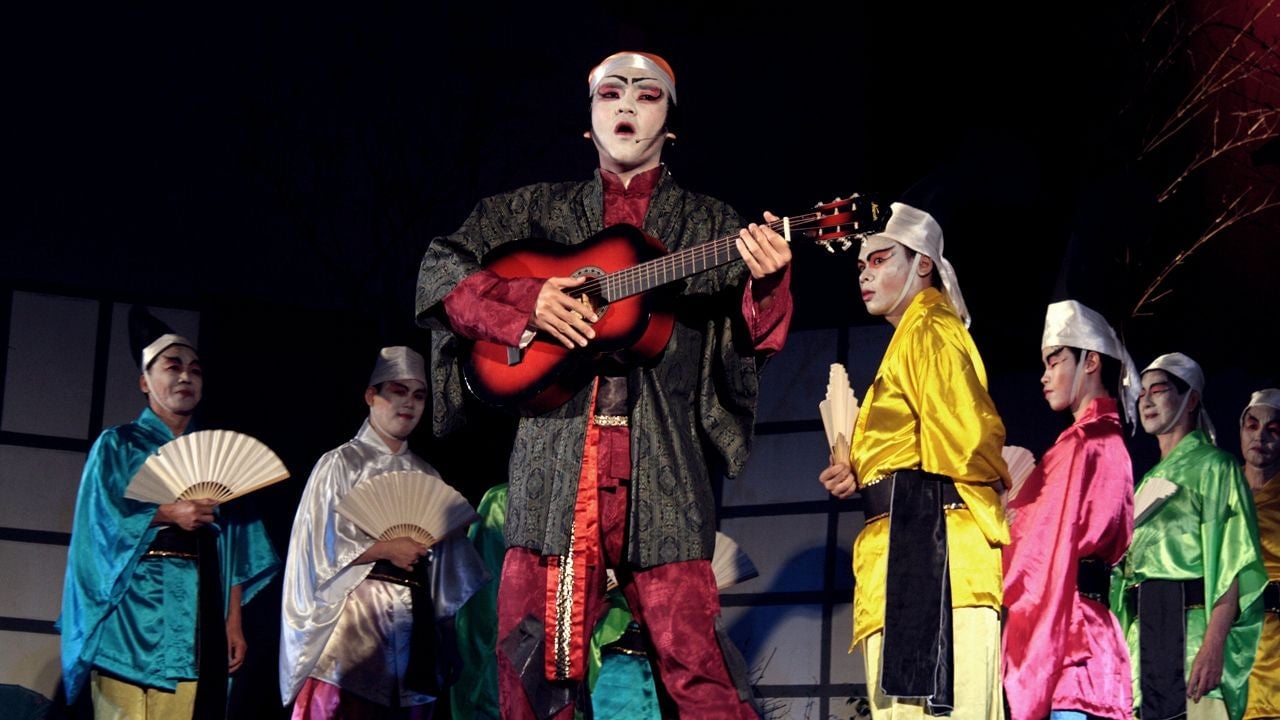

Like The Mikado, many of musical theater pieces written in the heyday of opera that ran from the late 1700s to the early 1900s reflect the ethnic clichés of the age. In fact, many of the best-loved operas used mysterious foreign characters or settings to tease new meaning from well-worn themes. Take for example Aida, Verdi’s Ethiopian princess heroine, or Bizet’s Sri Lankan pearl fishers, seen here below:

Puccini, by comparison, was more ambitious, setting entire operas in foreign cultures. The result was seldom a masterpiece of ethnic sensitivity. Turandot, for instance, offers up a violent vision of imperial China ruled by the eponymous man-hating dragon lady of a princess (whose advisers are named Ping, Pang, and Pong).

While Puccini more kindly exoticizes Japanese culture in Madam Butterfly, his child-bride protagonist is still a cartoon of submissive Asian femininity.

This, in spite of the fact that he rigorously researched his subjects, says Naomi André, professor at University of Michigan and co-author and editor of Blackness in Opera.

“Puccini is interesting in that he’s an Italian inheriting this big Italian opera tradition and yet he’s looking abroad for ideas,” André told Quartz. “When he’s looking at Madam Butterfly in Nagasaki and Turandot in ancient Peking, he was trying to get it right.”

Even with the best of intentions, these works transmitted the prejudices of their time. For instance, a main character’s heritage can function as an important part of the drama, as it does with, say, Aida. But often exotic looks can also be shorthand for clichés of temperament—the way Madame Butterfly‘s Asian-ness signals her self-sacrificing devotion, and Otello‘s blackness his rage.

As you can see in the images of Otello performances above, opera still treads close to the “blackface” line. However, Verdi’s Otello is a complex and ultimately sympathetic antihero. Asian female leading roles, on the other hand, come almost exclusively in two dimensions—a flimsiness usually accompanied by a liberal slather of facepaint.

Mary Rose Go, a Filipina-American soprano, says she’s ”always felt extremely uncomfortable” about productions of Madame Butterfly and Turandot—two Puccini operas that often involve gong-banging pageantry similar to The Mikado. And that’s even as opera producers are nowadays keen to cast someone who “looks the part.” Go says she opted out of the chorus section of a Madame Butterfly production in order to avoid ”a space where an Asian American’s worst Halloween nightmare can happen nightly in rehearsal,” as she put it.

“Madame Butterfly isn’t my voice type but, unless they re-imagined the production and got rid of the kimonos,” says Go, “I prefer not to be part of those productions.”

But few directors are scrapping the kimonos; indeed many argue these parodies of Eastern exoticism are essential to the work.

Avoiding the stereotypes—or reclaiming the role?

That’s somewhat galling given that the ethnic stereotypes of, say, the barbaric mysticism of the Far East have historically done real harm. Eric Hung, professor of music history at Rider University, points out that at the same time as works like The Mikado or Turandot were hitting the stage, the US was passing a raft of anti-Asian laws and, a few decades on, interning Japanese-Americans (in Seattle, as it happens).

It’s on that principle that performers like Mary Rose Go steer clear of hammed-up Asian roles. And there’s a long history among rising black singers in the middle of the last century shunning roles for which they “looked the part”; performers like renowned tenor George Shirley said they deliberately avoided taking traditionally black roles that would, in essence, remind directors that they were black and risk discouraging them from casting them in white roles.

That’s less of an issue today; the industry’s casting practices are often described as being “colorblind.” That doesn’t mean that non-white singers abound in white roles; though those performers are far more prevalent than they once were, white performers still dominate. So choosing to darken the features of white singers with makeup to make them look accurately ethnic is still an issue prone to giving offense; it also encourages the casting of singers whose looks approximate the race of a given character.

Though it might seem like crude typecasting, a director’s urge to cast a singer who “looks the part” isn’t necessarily bigotry—particularly in operas that are in one way or another about race. The most famous example is legendary soprano Leontyne Price’s performances of Aida in the 1950s through 1970s.

“There was a double resonance where, yes, she was an Ethiopian princess and she had a rough time and is singing about her love of her country,” says Michigan’s André. “But she was also an African-American woman in the era of Civil Rights singing in a discipline [dominated at the time by white performers].”

Few opera fans would deny that “double resonance” that Price or, these days, black sopranos like Latonia Moore bring to the role—a thrill that Verdi couldn’t have even guessed at. The power of those Aidas does not come simply from top-notch sopranos looking convincingly Ethiopian. Rather it’s the charge of immediacy that an African-American woman can bring to Aida’s aria about patriotism—meaning that wouldn’t have existed in 1900. A force, in other words, that comes when recent history is subtly acknowledged, not disregarded.

Reinventing exoticism

Even without obviously offensive roles to fix, many producers try to translate opera themes to modern audiences by using a broader cultural palate than those available in the early 1900s. And contrary to what traditionalists argue, that doesn’t mean renouncing the story’s original meaning, but rather allowing new depth to emerge, says Hai-Ting Chinn, a mezzo-soprano of Jewish and Chinese descent.

“I find some of these fusty old stories, and the operatic way of expressing them, more beautiful and compelling than a lot of newer things,” she told Quartz. “So I love trying to bring them to life for current audiences—I like finding human truth in the exaggerated artifice.”

For whatever reason, though, that’s easier said than done. Nearly everyone I spoke to recommended that directors more actively acknowledge opera’s past and present power to portray ethnicity—and, therefore, to show that staging choices are made with respect for those cultures:

- Program notes on historical context: It’s helpful to have program notes that explain the thoughts and historical context behind a composer’s choices, as well as how representation of race (or gender and sexuality, for that matter) and audience response have evolved. Though some opera companies do this at present, it’s not the industry standard. “It’s sad but opera audiences do tend to be older white wealthy people,” says Naomi André. “It’s not that that demographic doesn’t care—but they’re treated like they don’t.” Directors might want to explain any particularly edgy or controversial choices before the performance, say André and other sources.

- Colorblind casting doesn’t have to ignore race—it just shouldn’t exploit it: Puccini and Gilbert and Sullivan had exoticism to give their works extra punch. What do modern interpreters of their work have to replace it now that foreign cultures are no longer exotic? Casts of multi-ethnic performers and their audiences’ rich awareness of world cultures. These have the potential to layer provocative—and probably no less controversial—meanings into their productions. New York Times critic Anthony Tomasini points to a production of Aida (paywall) in which not only Aida and Amonasro, her father, were played by black singers (as often happens given that the characters are Ethiopian), but so too was Radames, Aida’s Egyptian paramour. “It made a compelling case that the conflict between these peoples was driven by national, sectarian and religious differences, not race,” he writes—apt given that the director, Francesca Zambello, set the production in the Middle East.

- More thoughtful staging: Is it possible to make an inoffensive The Mikado with mostly white actors? Sure, says Mary Rose Go. “I have seen pictures of productions that mixed the kimonos with multi-colored wigs and tennis shoes to reinforce the trope of satire and focus less on the Orientalism.”

These aren’t exactly tall orders—and many opera houses around the world already observe them, says Hai-Ting Chinn—particularly in “colorblind” casting. “But we can always do better,” she says. ”I want American opera to feel as well-mixed as I do, and for people not to care that Hansel is Chinese/Jewish and Gretel Kenyan/Aztec.”

“Maybe when we achieve that,” adds Chinn, “we won’t have to worry about ‘white’ people dressing up in whatever beautiful costumes they want.”