Automation + recessions = a radical shift in the shape of America’s jobs market

Over the past 30 years there’s been a shift and polarization of the American workforce. There have been fewer and fewer people employed in middle-wage occupations, mostly because “routine occupations,” jobs that can be performed by following a well-defined set of instructions, have been declining for years, and plummeted after the most recent recession.

Over the past 30 years there’s been a shift and polarization of the American workforce. There have been fewer and fewer people employed in middle-wage occupations, mostly because “routine occupations,” jobs that can be performed by following a well-defined set of instructions, have been declining for years, and plummeted after the most recent recession.

In a recent working paper, researchers from the University of British Columbia, Duke, and the Federal Reserve suggest they’re unlikely to return.

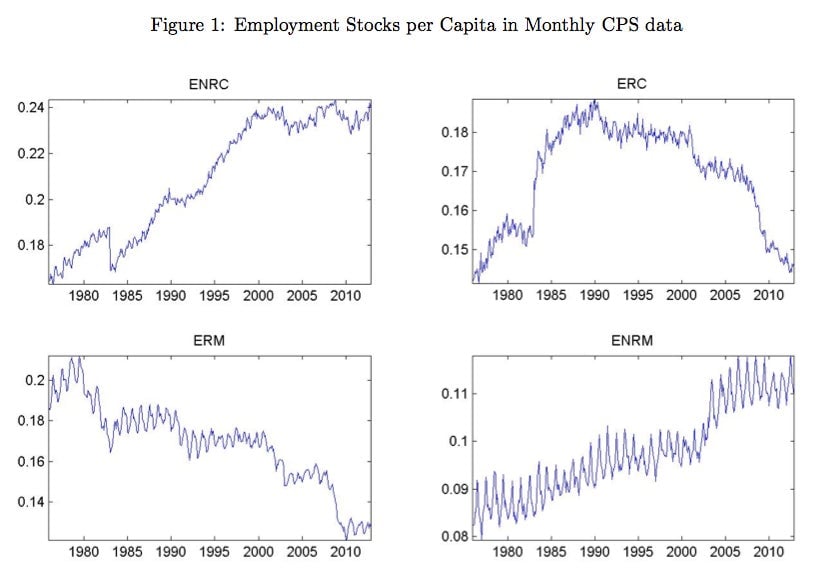

In the chart below from their paper, ENRC refers to people “employed in non-routine cognitive fields” (such as the creative professions or finance), ERC refers to routine cognitive fields (like data entry or administrative work), ERM is routine manual employment (e.g., an assembly line), and ENRM is non-routine manual employment, which includes many service professions.

As you can see, both types of routine employment have been declining steeply as a percentage of American jobs, while non-routine work grows:

The research paper, based on data from the Current Population Survey (the US’s main source of labor statistics) from 1976 to 2012, paints a fascinating picture of how this happened. The basics are easy to surmise. As technology has accelerated rapidly, companies have been laying people off during recessions, and turning to cheaper, automated solutions, requiring fewer, more flexible workers. When recessions end, they’re reluctant to go back.

About two-thirds of the decline in routine work is explained by increases in the number of people who lost these jobs, and by the rising fraction of unemployed people unable to get them. Changing demographics, the decline of unions, and outsourcing jobs to cheaper firms abroad—the kinds of things often blamed for job losses—explain only a small portion of the shift, according to the research.

Not all workers made it through this transition equally. According to the paper, women, and particularly educated women, were more likely to make the leap to non-routine work. But men, particularly non-college graduates, are more likely to be among those who lost a routine job, dropped out of the labor force, and never made it back.

The result has been fewer middle-class jobs for the less-educated. And as better computing makes it possible to automate a greater variety of routine cognitive work, more people who might once have been confident of a long-term middle-class career might find themselves out of luck. The winners are those who are good with people and can work in the service economy, or those whose skills can be enhanced, rather than replaced, by computers.