Why Mexico could not be happier that Washington and Colorado just legalized marijuana

Update (11/6, 9:11 PST): Voters in Washington and Colorado passed ballot initiatives today legalizing marijuana production and use; a third, on the ballot in Oregon, looks likely to fail. The measures could garner cheers in Mexico, where researchers hope legal marijuana could put a dent in cartel profits—if a reelected Obama administration allows it.

Update (11/6, 9:11 PST): Voters in Washington and Colorado passed ballot initiatives today legalizing marijuana production and use; a third, on the ballot in Oregon, looks likely to fail. The measures could garner cheers in Mexico, where researchers hope legal marijuana could put a dent in cartel profits—if a reelected Obama administration allows it.

Mexico and the US are tightly entwined economically—and this is as true of the illegal economy as the legal one. If popular ballot measures to legalize marijuana in Colorado, Washington and Oregon pass on Nov. 6, a respected Mexican think tank says that it will hit the cartels where it hurts: In the pocketbook, to the tune of several billion dollars. While tough police and military operations on both sides of the border have largely failed to slow the cartels, legalization would be “the biggest structural shock suffered by drug trafficking in Mexico since the massive arrival of cocaine in the late eighties,” the researchers wrote.

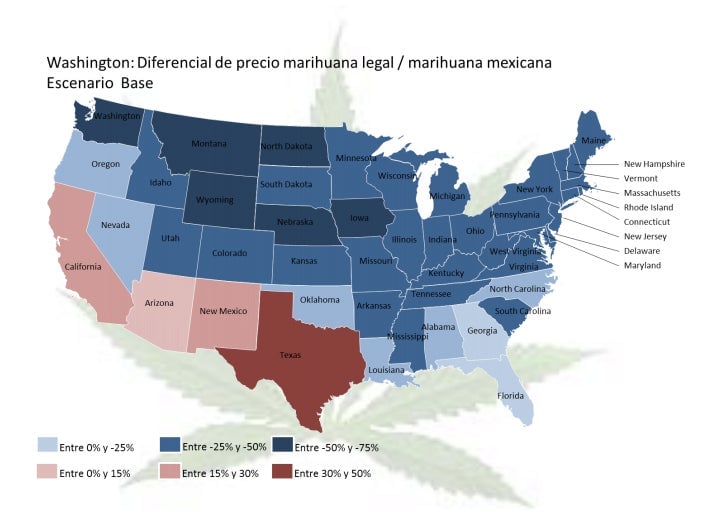

The report from the Mexican Center for Competitiveness (IMCO) (in Spanish) is based on an earlier study by the RAND Corporation, which determined that a 2010 ballot proposal could cut the income of Mexican drug dealers by 20%. The updated research suggests that cartels earn $6 billion each year from marijuana sales in the United States. If Washington, the state most likely to pass its ballot measure, does so, IMCO reports it will cut the cartels’ income by $1.37 billion, or about 23% of their revenue (though some cartels will be hit harder than others). Legalization in Oregon and Colorado would result in similar declines.

This would happen, the report assumes, because the infrastructure created by these ballot initiatives would result in cheaper and higher-quality domestic production of marijuana, which would also have less far to travel to reach its customers. That would drive Mexican pot purveyors, who face the costly challenge of crossing the border with their goods, at least partly out of the market.

But the development of a locally-regulated marijuana economy in an American state—and one vibrant enough to impact international competitors, at that—is the federal government’s worst nightmare. While the Obama administration came into office in 2009 promising to keep federal prosecutors off the backs of citizens following state guidelines for legal use of pot, all that changed when they saw states licensing growers and enterprising potrepreneurs shipping the stuff lucratively—and illegally—over state lines. The feds soon launched a legal campaign against not just marijuana distributors, but also the local lawmakers trying to build a regulatory framework for the marijuana economy.

IMCO cautions that a federal crackdown following legalization in these states could significantly limit the damage to the cartels. Given the Obama administration’s record and Mitt Romney’s campaign-trail policies, federal pressure on citizens operating in the new legal grey areas will be intense. If markets are to do what soldiers could not, and cripple drug smuggling operations, it will take a national policy change.

If that seems like another bridge too far, analysts like UCLA Professor Mark Kleiman caution that even a massive push for legalization won’t solve the public problems that come with drug use. He urges policymakers toward more pragmatic compromises between prohibition and legalization that might be more politically feasible for now.