One statistic illustrates the promise and peril of investing in Africa

Carolyn Campbell, founding partner of a $2 billion private equity fund focused on Africa, is bullish about the continent and quick to note that 14 African countries have better ratings on public integrity (pdf) than India, while 35 are seen as less corrupt than Russia, generating favorable comparisons with two other fast-growing economies seen as more welcoming to foreign investors than Africa.

Carolyn Campbell, founding partner of a $2 billion private equity fund focused on Africa, is bullish about the continent and quick to note that 14 African countries have better ratings on public integrity (pdf) than India, while 35 are seen as less corrupt than Russia, generating favorable comparisons with two other fast-growing economies seen as more welcoming to foreign investors than Africa.

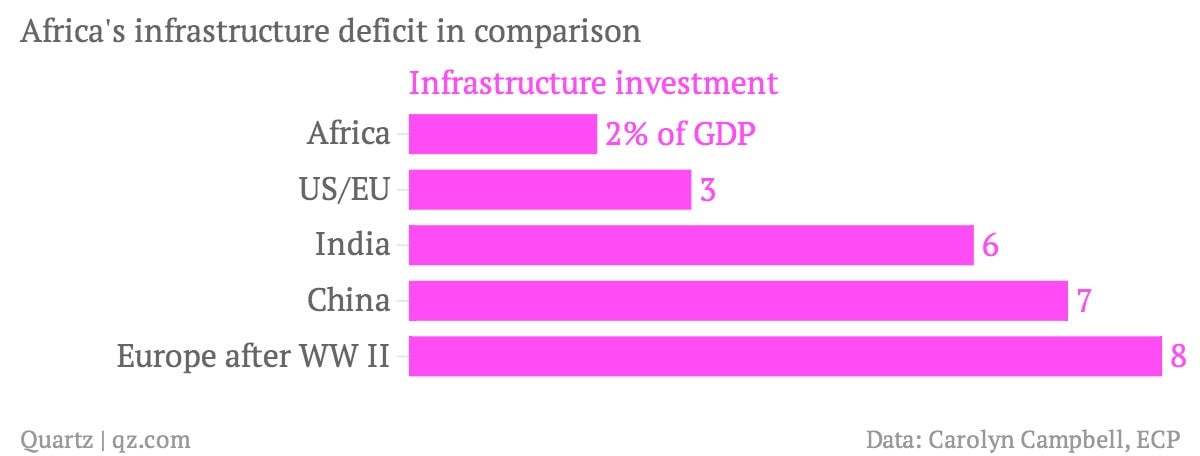

But one thing Campbell says that her fund, Emerging Capital Partners, can’t do is fill the massive gap in public investment in basic infrastructure: Europe, rebuilding after the devastation of World War II, spent 8% of its GDP on infrastructure. Today, China and India spend between 6% and 7%, while more mature economies spend about 3%. African countries average just 2% of public spending on infrastructure.

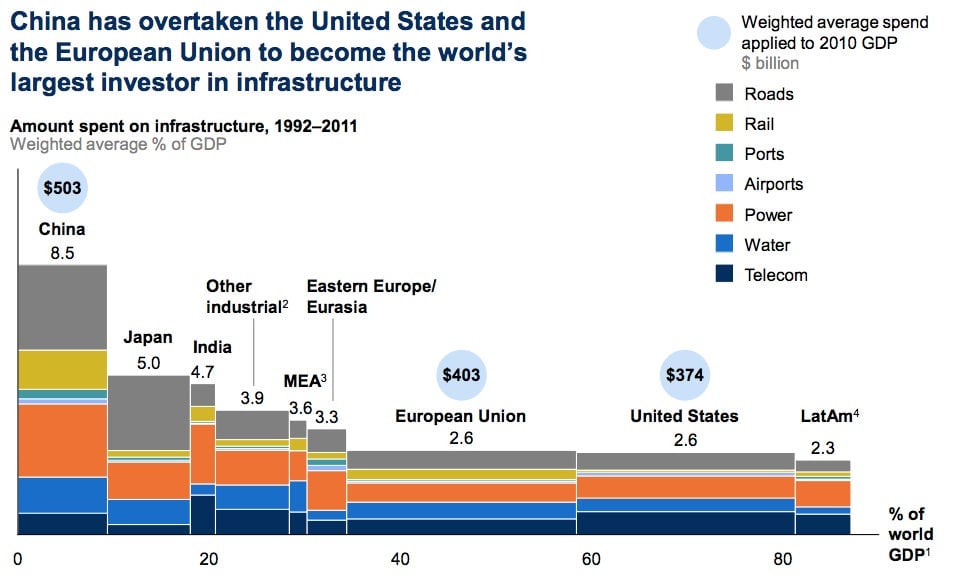

These types of comparisons aren’t easy to make across countries or time periods of fluctuating public spending; here’s a more granular view produced by McKinsey in January 2013, with Africa’s spending rolled into the Middle East:

For investors like Campbell, this deficit can be seen as an opportunity. Africa’s growth leaders, including Nigeria, Ghana, Mozambique, and Ethiopia, are set to expand their economies at rates of 6% or more this year—and that’s with relative underinvestment in infrastructure.

This week, African leaders have gathered in Washington for several days of talks with US officials, with the hopes of encouraging more foreign investment, particularly for electricity generation in sub-Saharan Africa, where two-thirds of the population lacks access to power. Not coincidentally, the summit’s other main theme is reducing corruption, including illicit financial flows made possible by US law. The challenge of infrastructure investment is that the public sector’s participation, the amount of cash involved and the propensity of such projects to go completely over-budget makes corruption a much bigger risk.

Managing the spending needed to make up this deficit, estimated at about $90 billion a year by the World Bank in 2010, and the vast differences in the providers of major infrastructure investment—from the China’s opaque investments and aid from Western governments to domestic tax dollars and private investment—will help determine whether African markets can replicate the miraculous catch-up growth seen in other developing countries.