Sergey Brin is missing the point of political parties in a democracy

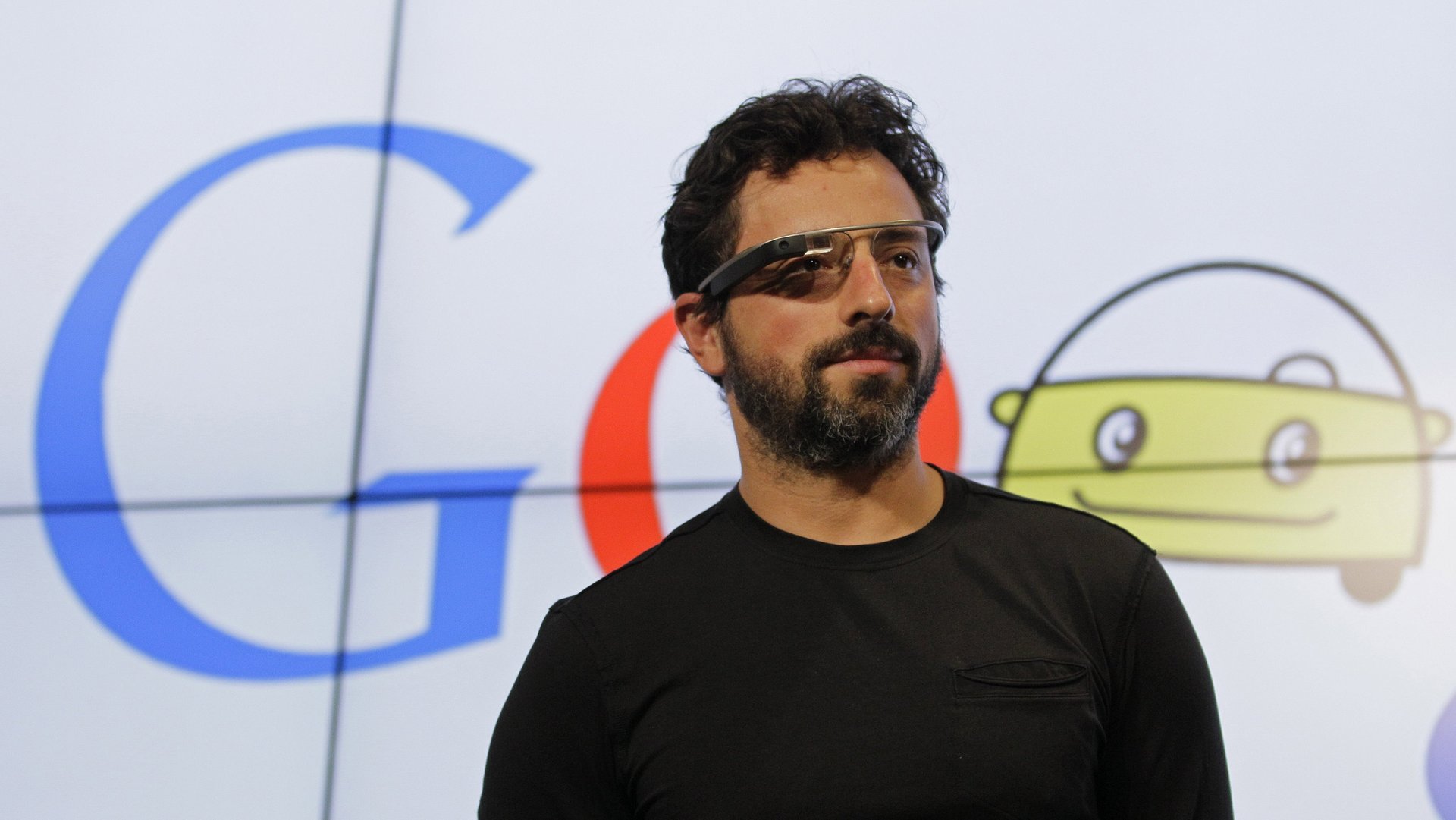

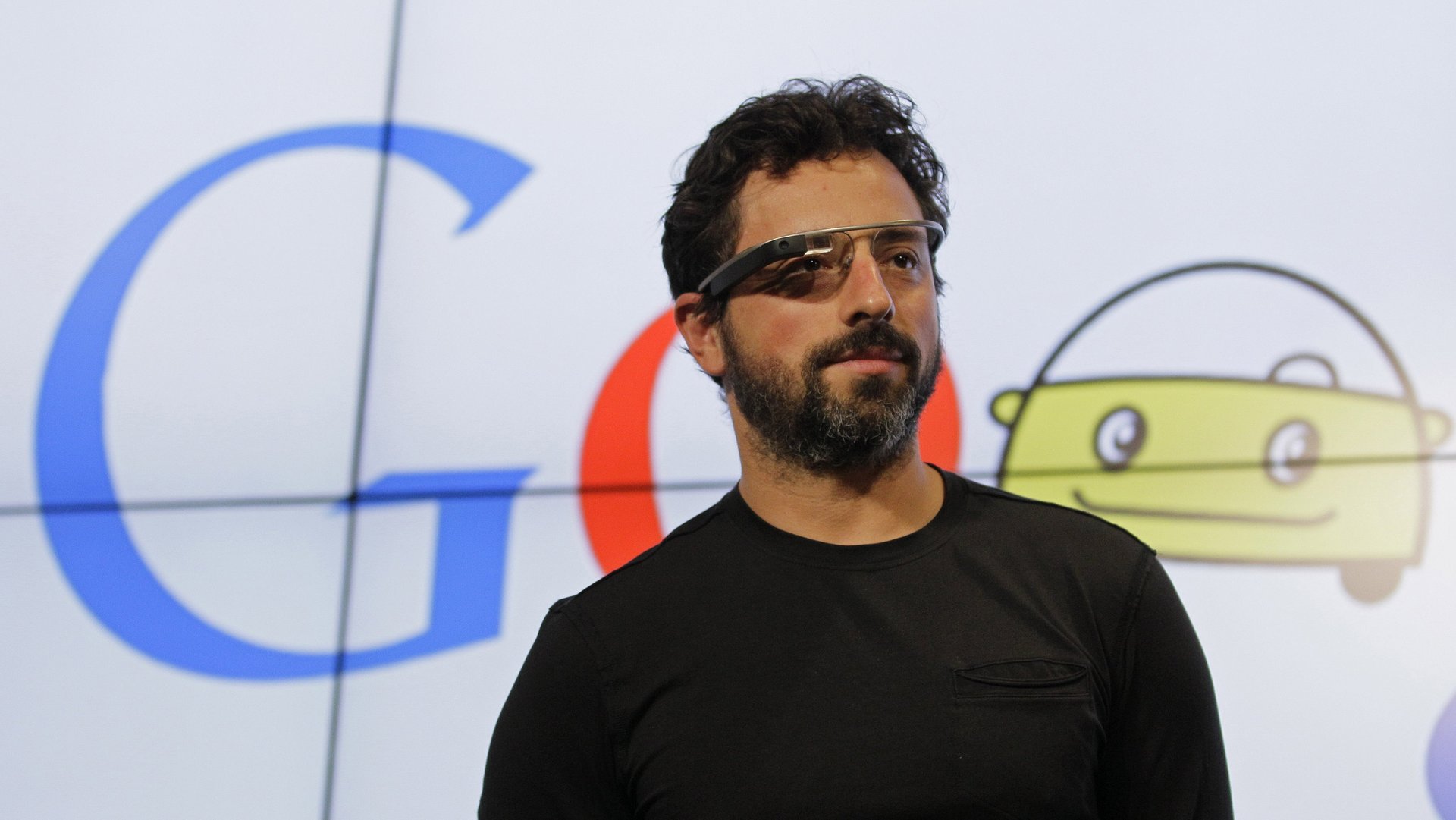

Sergey Brin, the Google co-founder, posted this pious election message on Google+ the night before America’s national elections:

Sergey Brin, the Google co-founder, posted this pious election message on Google+ the night before America’s national elections:

But because no matter what the outcome, our government will still be a giant bonfire of partisanship. It is ironic since whenever I have met with our elected officials they are invariably thoughtful, well-meaning people. And yet collectively 90% of their effort seems to be focused on how to stick it to the other party.

So my plea to the victors — whoever they might be: please withdraw from your respective parties and govern as independents in name and in spirit. It is probably the biggest contribution you can make to the country.

While it’s certainly easy to look at the gridlock in Washington and think “political parties are bad,” Brin is making a mistake—he’s assuming that the fundamental disagreements underlying that gridlock are caused by the parties, not demonstrated by them. In fact, well-defined parties that provide voters with a coherent policy platform and coordinated slate of candidates are considered necessary by political scientists [pdf]. That’s why organizations like the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme, the National Democratic Institute, and the International Republican Institute spend hundreds of millions helping new democracies strengthen their political parties—including in Brin’s native Russia, where weak parties are part of the countries poor transition to democracy since the end of the Soviet Union.

It doesn’t necessarily need to be a two-party system, but the idea is that voters should be able to express a clear choice at the ballot box and give an organized coalition a chance to implement it, with alternate parties offering criticism and opposition, so that government will be accountable to voters. America’s parties are fairly well-suited to perform this task, which is why most recent attempts to create third parties reflect a misunderstanding of the problems in Washington.

It’s true that party polarization has increased in the United States in recent decades, but the problems are caused largely by institutional design: American voters expect that a president and his party will be able to implement their agenda, but that’s frequently not true. Recent changes in Congressional practice mean that enacting most laws now requires a super-majority of 60 votes in the Senate, so that while President Obama was reelected, he can’t pass the jobs bill he campaigned on. If Mitt Romney had been elected, he wouldn’t have been able to repeal Obamacare or Dodd-Frank, two things that he has promised his supporters he would do. You may think that is bad or good, but it is not the fault of the party system. Many have called for the elimination of the filibuster, and there’s a chance that the new Senate may take up that task in January.

When Americans complain today about Congress’ focus on politicking over legislating, it’s easy focus on the team insignia, but studies show that even as people like Brin complain about the lack of compromise in Congress, they reward members of Congress who take partisan stands. Indeed, people’s political biases affect their perceptions of everything from the weather to pizza to the economy. Instead of asking for politicians to abandon their parties after election day, Brin might be wiser to ask voters to be more skeptical about parties—which could also have positive economic consequences. A study of European voters (pdf), who are generally more disillusioned with parties than Americans, found their partisan ennui led them to respond more strongly to economic conditions when making political choices, which makes for more accountability.