A British investment firm owns the Dutch company that printed the Indian design on the African dress for the US vice-president’s wife

Tuesday night, president Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama invited more than 50 heads of state to an outdoor dinner party at the White House, one of many events surrounding a three-day US-Africa Leaders Summit. At the party—which was decidedly less formal than an official state dinner—African leaders and their spouses’ fashion choices brought new levels of color saturation, hair volume, and flashy accessories to the White House.

Tuesday night, president Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama invited more than 50 heads of state to an outdoor dinner party at the White House, one of many events surrounding a three-day US-Africa Leaders Summit. At the party—which was decidedly less formal than an official state dinner—African leaders and their spouses’ fashion choices brought new levels of color saturation, hair volume, and flashy accessories to the White House.

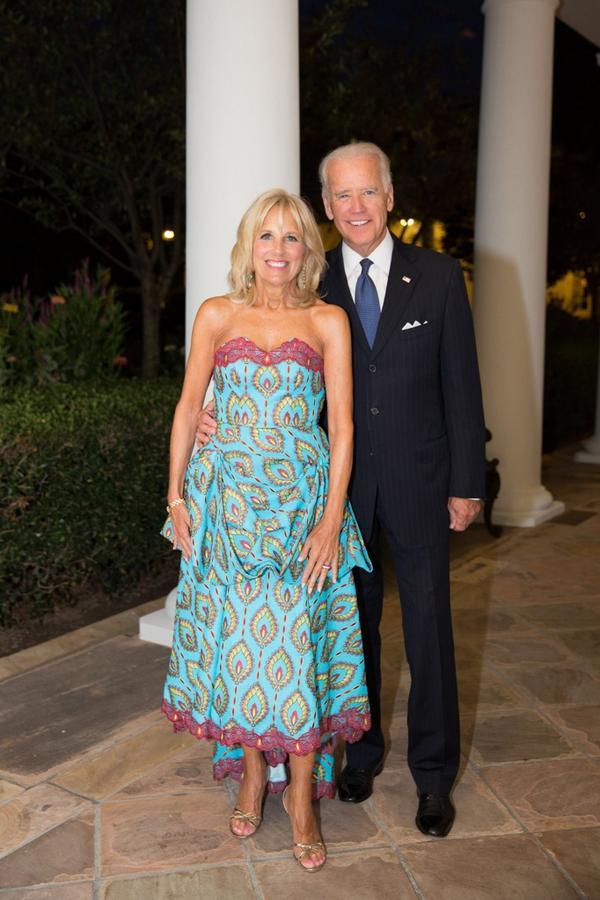

Jill Biden, the wife of US vice-president Joe Biden fit right in, glowing in a strapless, printed turquoise dress with hot pink trim and voluminous folds that fell below a fitted waist. The dress, reports the Washington Post, was a souvenir from a July visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo. The dress’ fabric was made by Vlisco, a Dutch purveyor of brightly colored printed fabrics portraying everything from hot-air balloons to chicken families. Biden picked out the turquoise fabric in Kinshasa, and a local seamstress subsequently worked all night to custom-create the dress in time for Biden’s departure the following morning.

Many perceive printed fabrics such as Vlisco’s, commonly known as “wax prints,” to be as distinctly West African. But while wax prints have certainly been widely adopted and reinterpreted in West Africa, their origins—and Biden’s dress—tell a tale of globalization, colonialism, development, and fashion.

Prints such as the one on Biden’s dress are often referred to as ‘Dutch wax,’ but their story starts in India with the resistance-dyeing technique called batik, which originally contained Hindu symbolism and significance (pdf). Batik’s popularity spread to what is today Indonesia—likely via Indian merchants—where the technique was further developed. By the 1600s, the Dutch had arrived in Java, and brought batik fabrics back to European mills with the intention of making cheap reproductions to sell back to colonies in the Dutch East Indies.

Two hundred years later, the Dutch had their printing technique pretty well dialed, except for one thing. Their mechanically produced prints had a crackled effect the Indonesians didn’t much like, so they needed a new market. Enter West Africa. Batik prints had already trickled into West Africa via European missionaries and West African soldiers who returned with batiks after fighting for the Dutch against the Indonesian resistance between 1810 and 1862.

By the end of the 19th century, European manufacturers were producing color palettes and designs specifically for the West African market. There, consumers favored the singular imperfections that the Indonesian market disdained. They were a hit.

By the 1920s, Vlisco—the Dutch company that made the fabric for Biden’s dress—was an expert wax printer, and within a decade, it would dominate West Africa’s import market. Nearly a century later, in 2010, the London-based private equity fund Actis acquired the company for $151 million. The African continent generated 95% of Vlisco’s €225 million in net sales the following year. Vlisco is still the luxury brand name in wax-print fabric, in a part of the world where custom-made clothing is a norm for the wealthy. (British designer Ozwald Boateng remembers the day he cut into a piece of his Ghanaian mother’s dear Vlisco cloth collection: “She lost her mind.”)

Today, the global fashion community—especially in the west—has fallen hard for Vlisco (and Vlisco-style) fabrics. Some lament their oversimplified identification as “African” prints, but they may not have to worry about it for long. China already has an eye on the technique.