These companies want to bring down America’s airline mafia

You might expect scrappy start-ups to steer clear of an industry plagued by bankruptcies, rising costs and accusations of monopolistic behavior. But the tough times facing the US airline industry have inspired a new crop of small carriers, all gunning to be the next JetBlue or Southwest.

You might expect scrappy start-ups to steer clear of an industry plagued by bankruptcies, rising costs and accusations of monopolistic behavior. But the tough times facing the US airline industry have inspired a new crop of small carriers, all gunning to be the next JetBlue or Southwest.

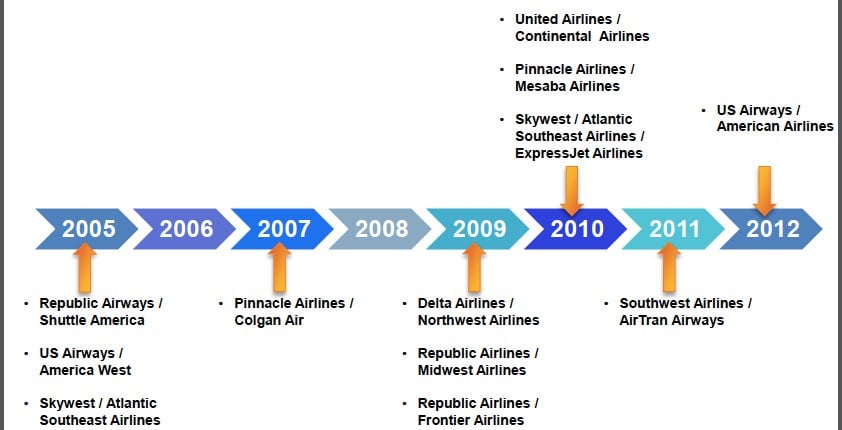

Mergers like last year’s deal between American Airlines and US Airways—which created the world’s largest airline—have given a handful of gargantuan companies control over most of the country’s domestic and international flights. (Four big carriers now control some 82% of domestic air travel). And yet, there are also more new, start-up airlines than the industry has seen in decades.

Among the challengers are upstarts like (paywall) American West Jets, which plans to connect Las Vegas and Orlando, Fla to Asian and African destinations; LaCompagnie, a business-class-only airline that started flying between Newark, NJ and Paris this spring; and People Express, a revived Newport News, VA-based carrier that’s angling to fill gaps left by Southwest.

The startups are tackling different ends of the market. People Express wants to tap budget travelers in US cities like Boston and West Palm Beach that lost local airlines to mergers. LaCompagnie is targeting business travelers who can do without high-end amenities like flat beds but still want other, somewhat less expensive perks.

But challenging Goliaths like Delta and Southwest will require serious grit. Not only can bigger airlines lure customers with more flights, frequent flyer programs and cheaper fuel costs; they also have the bargaining power to muscle out competitors for airport spots, airplanes and pilots.

For instance, to thwart competition from new carriers, Delta has been fighting the advent of a second airport in its hub city of Atlanta, the country’s ninth largest metro area (the airline controls 78% of the existing airport’s passenger traffic). Big airlines can spread their fleet costs over longer periods; they have more sway over how information is displayed on airline search sites, and more cash to throw at the dwindling crop of American commercial pilots.

It’s no wonder that less than 20% of US carriers launched since the late 1970s are still around. The signs of hope? Passenger numbers are rising globally, especially out of Asia, as are profits for American carriers. If upstart carriers can’t steal a slice from bigger rivals, they’ll have to bank on growing the pie.