Why the enormous casino that was supposed to save Atlantic City is shutting forever

Revel, the $2.4 billion mega-casino that was supposed to bring Atlantic City back, seemingly had everything: gorgeous design, luxurious spas, ocean views, and Michelin-starred chefs. What it didn’t have was customers—at least not enough of them to stay solvent. The casino has declared bankruptcy twice in the two years it’s been open, and is now set to shut down by Sept. 10 after failing to find a buyer in a court-supervised auction.

Revel, the $2.4 billion mega-casino that was supposed to bring Atlantic City back, seemingly had everything: gorgeous design, luxurious spas, ocean views, and Michelin-starred chefs. What it didn’t have was customers—at least not enough of them to stay solvent. The casino has declared bankruptcy twice in the two years it’s been open, and is now set to shut down by Sept. 10 after failing to find a buyer in a court-supervised auction.

More than 3,000 employees will lose their jobs.

For those watching the casino’s struggles, the closure seemed fairly inevitable. Here’s are a few of the many factors behind the collapse.

Gambling for everyone!

When New Jersey decided to allow gambling in Atlantic City in 1978, it was a novel move—it was the only state other than Nevada to give its blessing to the casino business. But since then, nearby New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland have legalized gambling and seen large developments of their own.

The result has been a massive decline in business for Atlantic City. Gambling revenue there dropped 44% between 2006 and 2013, according to a Moody’s report. The falloff has been so dramatic and the industry has been so central to the city’s economy that the ratings firm downgraded Atlantic City’s municipal bonds in June to junk status. The Atlantic Club closed earlier this year, the Showboat may shut down as well, and the Trump Plaza is slated to shutter shortly after Revel.

The whole country is approaching gambling oversupply, according to the New York Times (paywall), as states race to build casinos and collect tax revenue.

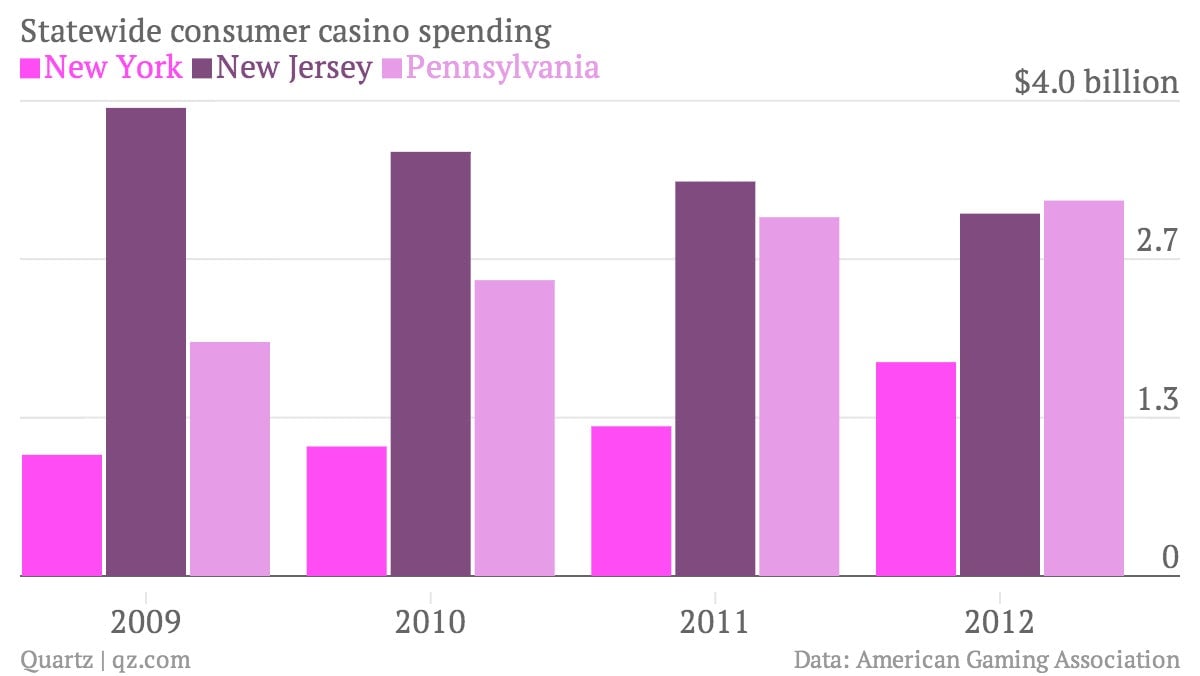

Pennsylvania passed New Jersey in casino spending back in 2012:

Targeting a narrow demographic

The idea behind Revel was to counter the out-of-state competition by becoming a genuine, Las Vegas-style luxury destination.

Revel was designed to attract a younger crowd and resort goers who otherwise wouldn’t have considered Atlantic City. It bet far too much on that strategy. All of the spending didn’t make it immune to the region’s decline, just more expensively subject to it.

That luxury focus was not only expensive, it alienated Atlantic City’s core gambling customers, who tend to be older and less wealthy. The expensive restaurants, the no smoking policy (since rescinded) and perceived attitude of the place actively drove people away (paywall). This might not have mattered so much if the resort’s target customers had shown up—but they didn’t.

As a result, the glitzy new Revel massively underperformed casinos that were far older, smaller, and less luxurious. The Trump Taj Mahal, for example, is apparently so worn down that Donald Trump is suing to remove his name from the property, along with the Trump Plaza (he operates neither).

Here are gross revenue figures through June 2014, courtesy of the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement. Revel had more authorized gaming space than any casino except for the Borgata:

Borrowing big

On top of declining casino revenue and significant operating losses (in the range of $20 million a quarter), Revel started off with a massive debt load. Morgan Stanley, an initial backer, washed its hands of the project in 2010 and took a $1 billion writedown on its investment before the property’s development was even finished.

The combination of the losses, two bankruptcies, and a dearth of willing buyers means the end of Revel as a casino. Now there’s discussion of turning the giant glass structure on the waterfront, Atlantic City’s tallest building, into luxury condominiums.