Six charts to show that the Great Barrier Reef is in deep trouble

The future of Australia’s iconic Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral structure and an unmatched biodiversity haven, looks grim. That’s the conclusion of an Australian government report, which finds that the reef’s outlook is ”poor, has worsened since 2009 and is expected to further deteriorate,” due mostly to global warming but also the effects of chemical run-off, coastal development, and fishing.

The future of Australia’s iconic Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral structure and an unmatched biodiversity haven, looks grim. That’s the conclusion of an Australian government report, which finds that the reef’s outlook is ”poor, has worsened since 2009 and is expected to further deteriorate,” due mostly to global warming but also the effects of chemical run-off, coastal development, and fishing.

Here’s a look at what’s going wrong:

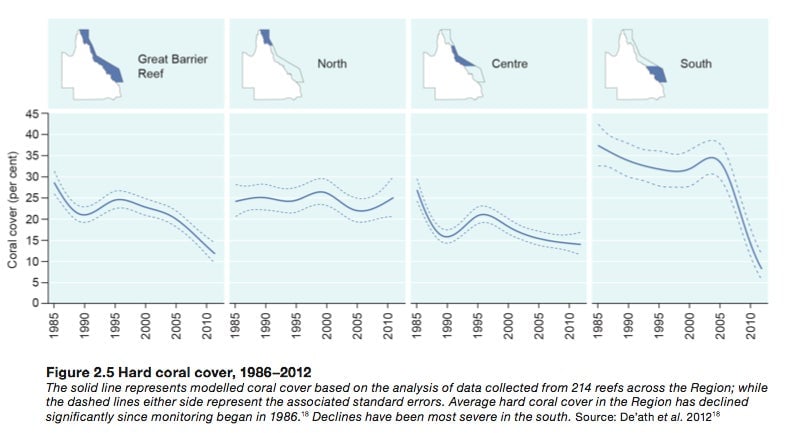

The coral is shrinking

Hard coral, which makes up most of the reef’s structure, has a skeleton made of calcium carbonate—the same stuff as chalkboard chalk. It has a symbiotic relationship with algae that live within its tissue. The report found that the the average hard coral cover has declined from 28% to 13.8% (pdf, pg 20), with a rate of decline that has increased dramatically in recent years. The decline has been worse in the southern parts of the reef, and less severe in the northern parts.

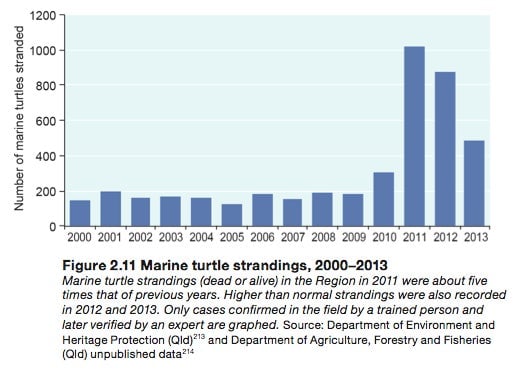

Turtles are getting stranded

The reef is home to six of the world’s seven marine turtle species. The last three years have seen high numbers of turtles getting stranded because of reductions in available seagrass (pdf, pg. 45), their primary food source. Seagrass meadows have declined, partly because of poor water quality, but also because…

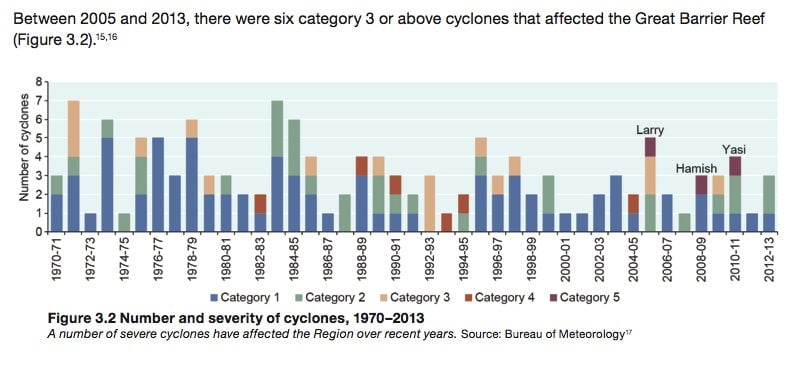

Mega-storms are becoming more common

“In addition to strong winds and rain, the powerful waves generated during cyclones can seriously damage habitats and landforms, particularly coral reefs and shorelines. It is estimated that cyclone damage has been one of several factors in coral cover loss.” (pdf, pg. 64)

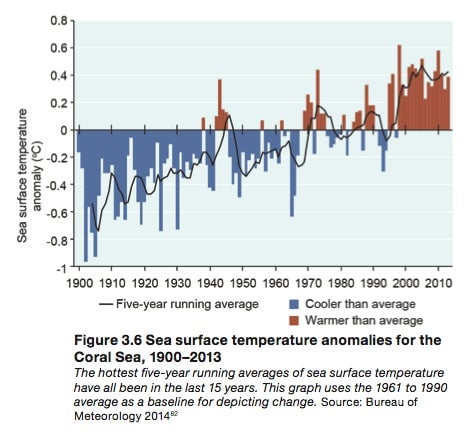

Sea temperatures are rising

“Sea temperature is a key environmental factor controlling the distribution and diversity of marine life. It is critical to reef building and is one of the key variables that determine coral reef diversity and the north-south limits of coral reefs,” the report explains. “The average sea surface temperature in the Coral Sea has risen substantially over the past century. Since instrumental records began, 15 of the 20 warmest years have been in the past 20 years.”

When temperatures rise, the relationship between corals, algae, and other animals breaks down: “If sea temperatures exceed a certain threshold these algae are expelled — an effect known as bleaching.” There have been nine “mass bleaching events” since 1979—most severely in 1998 and 2002, and most recently in 2006.

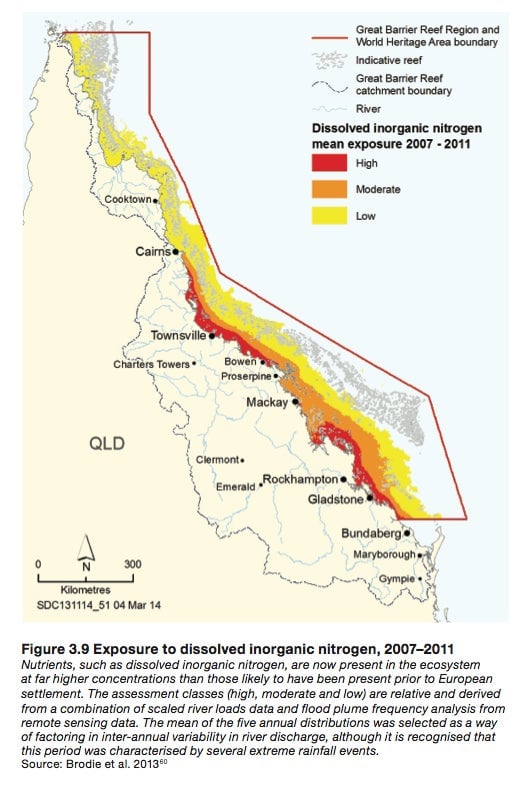

…And so are nitrogen levels

In proper quantities, nitrogen is essential to plant life. But in excess—as in the US city of Toledo this month—nitrogen from human waste and agricultural runoff can result in “algae blooms” that destroy other marine life. The report found that nitrogen levels on the Great Barrier Reef are at an all-time high (pdf, pg 50), “which can affect ecosystem health, for example through reducing available light for seafloor communities and trapping sediment.”

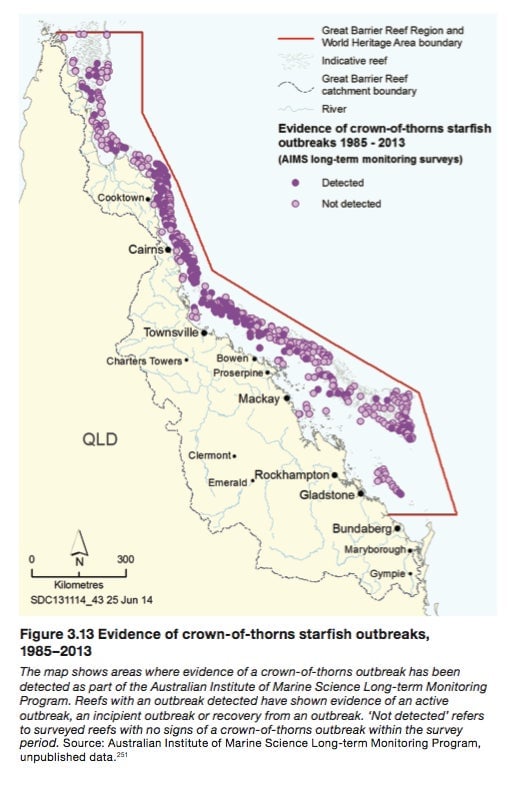

Crown-of-thorns starfish are bad news

Simply put, crown-of-thorns starfish eat coral. When the reef is healthy, they serve an important role by eating the faster-growing coral and giving slower-growing coral room to form bigger colonies. But when nutrient levels in coastal waters are low, as they have been, the population of the starfish explodes. There is also evidence that land-based runoff can cause crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks.

Australian authorities have had some luck killing the starfish with toxic injections, but that may be just a short-term fix. The report concludes: “One indicator of declining ecosystem health is that crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks are becoming more frequent. Rather than experiencing outbreaks in a natural cycle of about every 50 to 80 years, the Reef has been affected by three in the past 50 years and a new outbreak has begun.”