There’s something a lot more valuable you can do in college than getting good grades

When I was 17, if you asked me how I planned on getting a job in the future, I think I would have said: Get into the right college. When I was 18, if you asked me the same question, I would have said: Get into the right classes. When I was 19: Get good grades.

When I was 17, if you asked me how I planned on getting a job in the future, I think I would have said: Get into the right college. When I was 18, if you asked me the same question, I would have said: Get into the right classes. When I was 19: Get good grades.

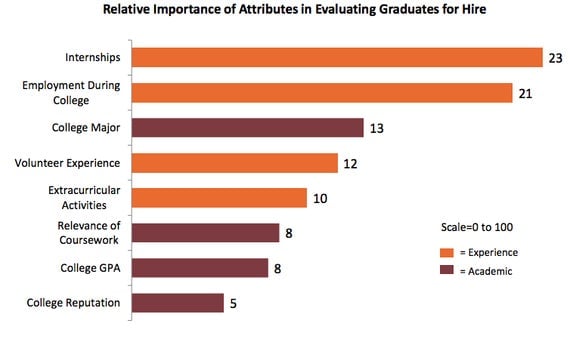

But when employers recently named the most important elements in hiring a recent graduate, college reputation, GPA, and courses finished at the bottom of the list. At the top, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education, were experiences outside of academics: Internships, jobs, volunteering, and extracurriculars.

What employers want

“When employers do hire from college, the evidence suggests that academic skills are not their primary concern,” says Peter Cappelli, a Wharton professor and the author of a new paper on job skills. “Work experience is the crucial attribute that employers want even for students who have yet to work full-time.”

Before you retreat to the comment section and scream at me for saying that school, classes, and grades don’t matter, let me say: I don’t think this should be interpreted as a sign that schools, classes, and grades don’t matter. Employers might not crave academic skills. But students often qualify for the “right” internships by getting good grades in relevant classes at challenging schools. In this calculation, a strong academic record buys you a strong experience record, so when an employer is evaluating your internships, he’s indirectly evaluating your academic achievements, too.

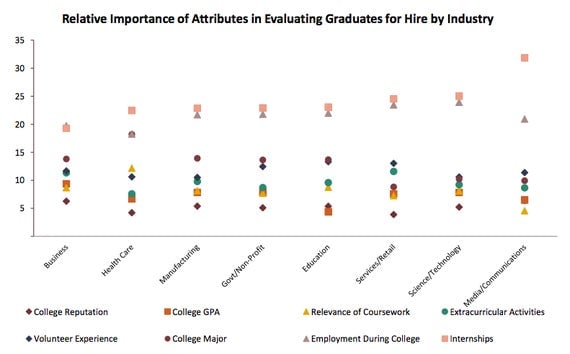

But the US economy isn’t a monolith: Do some industries care more about internships than others?

The Chronicle has the answer: Media and communications companies are gaga for internships and uniquely indifferent toward your classes. Health care companies care the most about your major, and white-collar businesses care the most about your GPA. Ironically, education employers care the least about grades.

What employers want: by industry

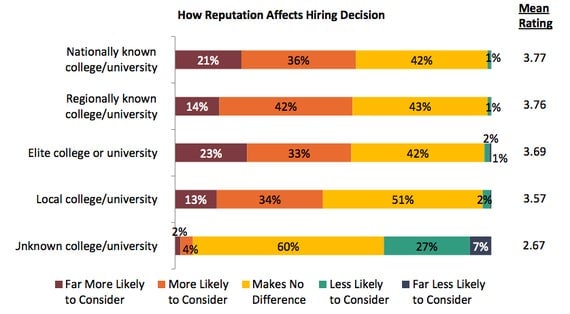

Can America’s employers really be that indifferent toward what college I attend? Could they really read “Harvard University” and just see “University?”

Consider the larger picture. Every year, about 3 million people start their first year of college in this country. About 1,600 of them enroll at Harvard. That means that, relatively speaking, nobody goes to Harvard. Harvard does not exist. Add up all the capital-E Elite schools that jostle for the top 20 national universities and colleges in US News’ annual rankings, and you’ve reached just 1% of the higher-ed population.

So, while it’s true that some consulting firms and banks take first-years exclusively from these campuses, they are fishing in a minuscule pond. Their elitism is diluted in a survey that spans the entire economy.

When you drill down into how a college’s reputation affects hiring, employers’ mean rating of “regionally known” colleges and universities was practically indistinguishable from their rating for elite schools.

The effect of school reputation

Internships occupy an awkward place in our labor market and in our lives. Many of them are indistinguishable from jobs; but while unpaid jobs are considered immoral, unpaid internships are considered common. On a day-to-day basis, even desirable internships can resemble worthless months of servitude, where meaningless tasks interrupt long stretches of numbing boredom. Yet, employers will eventually regard these agonizing periods of numbing boredom to be the most significant professional moments of our college career.