Commuters think biking to work is fine, but there are better ways to get there

For most people, a satisfying commute is not necessarily a happy one—a not-so-unhappy one will do. Yes, it’s true that the ideal commute is not absolutely zero commute; many of us can use the time to decompress or get some thinking done. But it’s also true that beyond a certain point—roughly 15 minutes one-way, on average—we just want our lives and sanity back.

For most people, a satisfying commute is not necessarily a happy one—a not-so-unhappy one will do. Yes, it’s true that the ideal commute is not absolutely zero commute; many of us can use the time to decompress or get some thinking done. But it’s also true that beyond a certain point—roughly 15 minutes one-way, on average—we just want our lives and sanity back.

Even within that general framework of unpleasantness, some commutes are more enjoyable than others. A group of researchers at McGill University in Montreal recently tried to establish a clear hierarchy among the main six work-trip modes: driving, riding (bus and metro and commuter rail), walking, and cycling. They asked nearly 3,400 people who commuted to campus on a single mode to describe their typical trip in both winter and summer, and to rate their satisfaction with various aspects of that trip. The researchers then converted the ratings into a single satisfaction score for each of six commute modes.

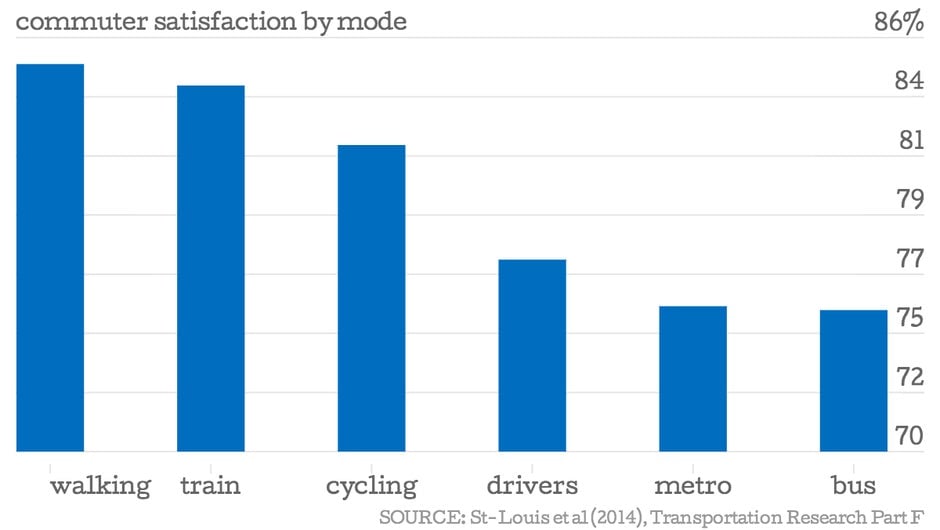

We’ve charted the results below, but in case you can’t wait that long, here are the raw (rounded) percentages: pedestrians (85%), train commuters (84%), cyclists (82%), drivers (77%), metro riders (76%), and bus riders (75.5%).

The first thing that’s clear is that, in keeping with previous surveys, active commuters tend to enjoy the journey more than those who passively endure either traffic congestion or transit crowds. But commuter-rail passengers in this survey enjoyed the trip, too—in this sample, even more than bike riders. That result likely speaks to the ability to be productive on the train.

These top three modes received significantly higher satisfaction ratings than did driving and riding the metro or the bus, which clustered around the 75% to 77% area—creating a sort of two-tiered commuter satisfaction system. Then again, no one was entirely immune from commuting complaints: Walkers and cyclists were less satisfied with their trip in cold seasons, and rail commuter satisfaction went down if the trip wasn’t productive.

Those are the basics. But drilling down into the details, the researchers find some notable wrinkles. One, not surprisingly, is that travel time accounts for much of the difference between the two tiers. Longer travel time led to lower satisfaction whatever the mode, but walkers, train riders, and cyclists were the least affected by time variables—again, no doubt, because they enjoy the commute itself, rather than seeing it as a means to an end. The satisfaction of drivers and bus riders also took a hit with additional “budgeted” trip time, likely on account of unpredictable traffic.

A direct comparison of the 439 cyclists and 516 bus riders in this sample shows the impact of time on satisfaction more clearly. The bike riders enjoyed their trip much more than the bus riders, even though both groups commuted roughly 22 minutes on average. And while cyclists only budgeted 5 extra minutes a day for trip delays, bus riders budgeted 14 minutes. That’s more than an hour a week set aside by bus riders just to be sure they aren’t late for work, and perhaps the same amount on the other end to be sure they’re home for dinner.

External factors like traffic and transit frequency didn’t explain the whole picture. People expressed more happiness with their commute when the mode they took was the mode they wanted to take.

Interestingly, this finding cut both ways. So satisfaction among bus and metro riders decreased when they preferred to drive—perhaps reflecting captive riders dissatisfied with local service. But drivers who wanted to ride transit more often were less satisfied with their trip, too. This group might consist of people who live in transit deserts, or who drive because their transit commute would take much, much longer. In the words of the researchers:

It seems that the desire, or the need, to use a mode of transportation different than the one currently used negatively influences satisfaction.

The typical caveats about self-reported happiness apply, here, and asking people to recall typical commutes from various times of year—in this case, warm and cold seasons—brings the weakness of memory into the picture. It’s also less than ideal that half the respondents were students, a population that might not yet appreciate the full gravity of the daily grind. Last, the comparison might have been stronger if the researchers had controlled for time, given how critical it is to any commute.

So keep those concerns in mind as you taunt the coworker with the terrible drive to work, and this, too: At the end of the day, even a relatively not-so-unhappy commuter has to do it again tomorrow.