The story of Elon Musk and GM’s race to build the first mass-market electric car

One of the hottest clashes in technology pits two pathmakers in the new era of electric cars—Tesla and General Motors. Both are developing pure electrics that cost roughly $35,000, travel 200 miles on a single charge, and appeal to the mass luxury market.

One of the hottest clashes in technology pits two pathmakers in the new era of electric cars—Tesla and General Motors. Both are developing pure electrics that cost roughly $35,000, travel 200 miles on a single charge, and appeal to the mass luxury market.

The stakes are enormous. Most electrics have less than 100 miles of range. Experts regard 200 miles as a tipping point, enough to cure many potential electric-car buyers of “range anxiety,” the fear of being stranded when their battery expires. If GM and Tesla crack this, sales of individual electrics could jump from 2,000 or 3,000 vehicles a month to 15 to 20 times that rate, shaking up industries from cars to oil, which were until now certain that large-scale acceptance of electrics was perhaps decades away.

It is a substantial gamble for both companies. Tesla CEO Elon Musk has more or less bet his company on the contest. GM’s existence is not in jeopardy if it loses, but the outcome could still determine its place in the next generation of automaking.

The potential prize is not only profit, but outright technology leadership—the intangible aura that made Apple under Steve Jobs an outsized triumph. In this respect, the parvenu Tesla—just a decade old—holds the advantage. Musk’s first two models, with their grace, attitude and electronic showmanship, have dazzled critics, buyers and especially Wall Street. GM has impressed critics, too, with its Chevy Volt, which led the advent of plug-in hybrids, but there are doubts that it can best Musk in direct competition. However, if it can show it is generally Tesla’s equal, it would achieve unexpected street cred, while Musk would appear much more mortal.

There already is a 200-mile car but it is expensive

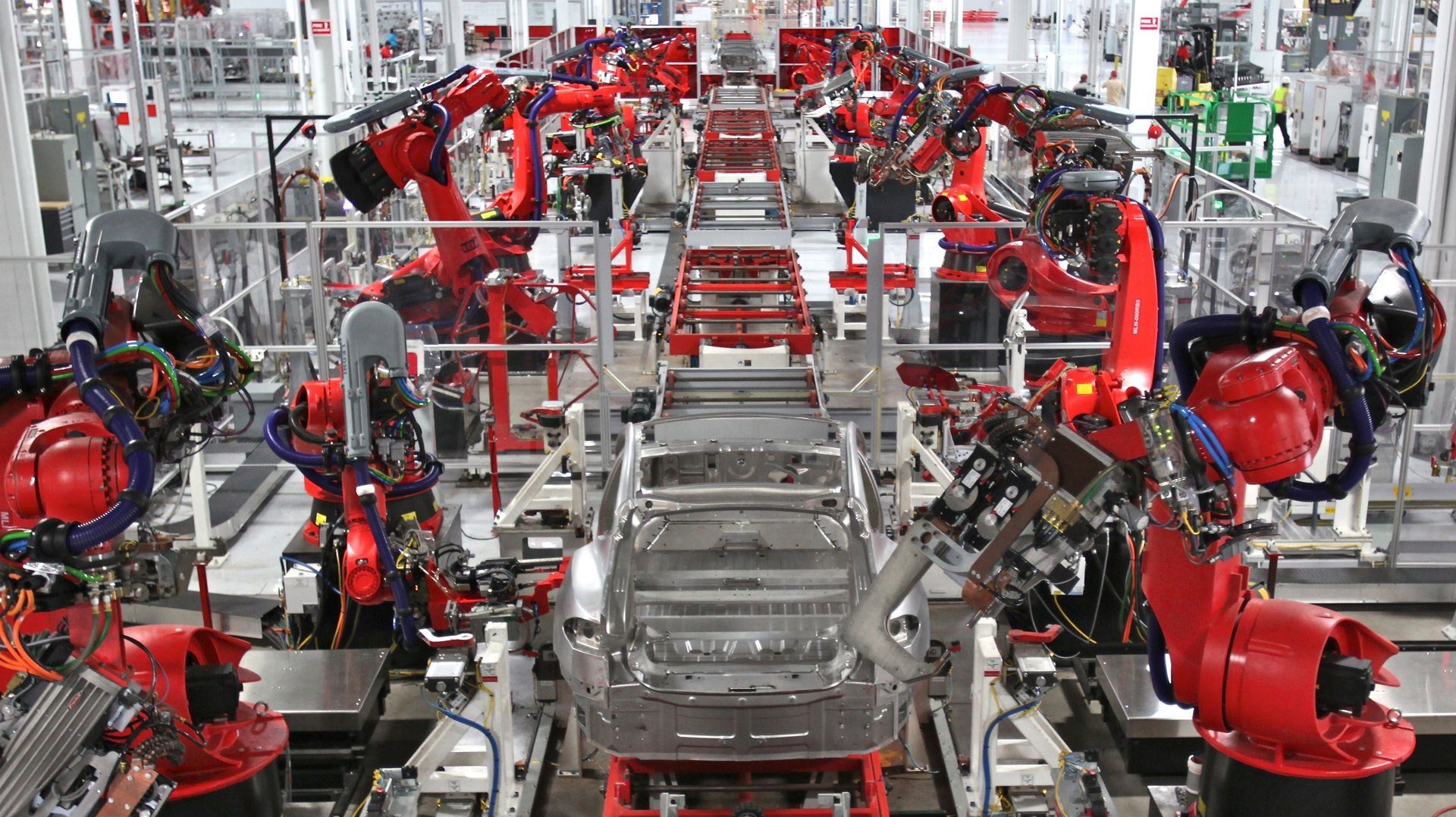

The only major 200-mile car currently is the Tesla S (pictured above). Its 60-kilowatt-hour (kWh) basic version promises 208 miles of range on a single charge, while the top-of-the-line 85-kWh car will go 265 miles. Musk says moreover that he plans to sell an upgraded battery for the original Tesla Roadster that will take it 400 miles on a single charge.

But there is a price to such distance. The 208-mile S starts at around $70,000 and the 265-mile model at $80,000, with optional extras adding tens of thousands more. Musk said all along that his strategy was to break in to the industry with super-luxury vehicles, then move down-market. The 2008 Roadster debuted at a base price of $98,000 and advertised at 245 miles on a single charge.

GM launched the Volt in 2011 at $41,000. But by last year, Tesla’s sensational success had it worried. Then-CEO Dan Akerson said Tesla was a threat, and assigned a group of employees to monitor the newcomer. In 2012, Akerson was overheard bucking up employees with the promise that GM was getting close to a 200-mile car, a vow he repeated last year as well.

The angst has only deepened over the last 13 months. Wall Street has worked itself up into a frenzy over Tesla, doubling its share price to 78 times projected earnings—a dotcom-era number—compared with GM’s 7.5 times. Last month, a relaxed and confident Musk disclosed the name of his next-generation 200-mile car to a British journalist: the Model 3. It would be unveiled in late 2016 and go on sale the following year, he promised. Media- and image-savvy, he said it would be aimed at buyers, not of GM cars, but of BMW’s 3-Series, its $35,000 entry-level vehicle. Motorists bought 500,000 of the BMWs last year, and Musk predicts he will be selling that many vehicles per year by 2020.

Two days later, LG Chemical said that it had a lithium-ion battery that, too, would be ready for a 200-mile car in 2016. LG did not say which carmaker wanted the battery, and GM remained silent. But LG is GM’s supplier, and most experts say its battery will go into a GM vehicle.

Both companies declined to comment for this article. Musk publicly belittles (video) GM, refusing to concede that it is a true rival. Yet the mid-$30,000 price range puts him squarely on GM’s turf. For GM’s part, it simply cannot ignore Musk’s challenge. The contest has been joined.

But the physics are daunting

Getting 200 miles of range in a $35,000 car will require a battery that can leap over the best lithium-ion technology known to be within reach. And to be ready for 2017 or even 2018 models, it has to accomplish the jump with astonishing speed.

Consider the current state of the art in moderately priced pure electrics—the $29,000 2015 Nissan Leaf. (GM’s Chevy Volt is a plug-in hybrid containing both a 37-mile battery and a gasoline-driven engine.) The Leaf’s range is only 84 miles. So Musk’s Model 3 or GM’s rival to it will have to perform two-and-a-half times as as well while barely budging in price.

A lithium-ion battery usually relies on expensive layers of metal oxides. Like the Volt and Tesla S, the Leaf has a battery made of lithium, nickel and cobalt; as a third metal, GM and Nissan use manganese (their battery chemistry is called “NMC”) while Tesla’s battery instead contains aluminum (and is called “NCA”).

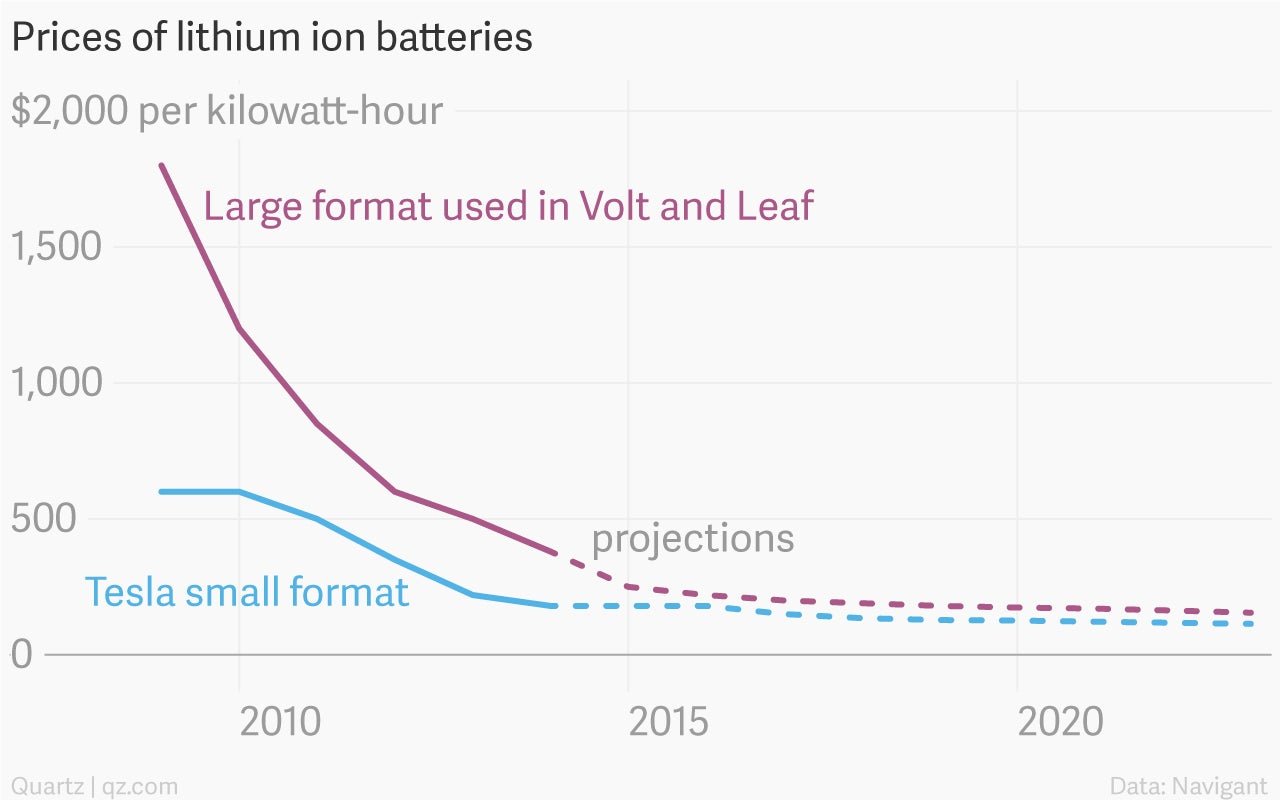

Carmakers disclose few details about the cost of their lithium-ion batteries but, according to Navigant, a research firm, they are about $380 per kWh for the type of cells in most electric cars, including the Leaf. If so, about $9,120 of the Leaf’s sticker price—or 31%—is the cost of its 24 kWh battery.

Navigant expects that as lithium-ion batteries get cheaper, by 2020, Nissan could stuff half again as much energy into the same size battery at the same price (see chart below). All things being equal, that would give you about a 170-mile Leaf—nice, but still short of the aim. Musk’s battery economics are superior (see next section), but even so, a cheap 200-mile battery seems far off.

One trigger point for a better lithium-ion battery could be its negative electrode, known as the anode. All current lithium-ion batteries use graphite anodes. But scientists say a big jump in performance would be possible if they could perfect a silicon anode, which would absorb far more lithium than graphite, increasing how much energy could be stored. The problem is that in tests thus far, silicon expands, cracks and kills the battery. The US government is funding six efforts to create a working silicon anode that can go commercial, but even if one or more are successful, they would not deliver a 200-mile car by 2017 or 2018.

Absent a silicon anode in a lithium-ion battery, says Kevin Gallagher at Argonne National Laboratory, whose specialty is projecting the costs of advanced batteries, the scientific consensus is that a 200-mile car can’t be built at a moderate price. But, he told Quartz, “obviously Elon doesn’t agree with the consensus.”

How Musk intends to get there

Getting to a $35,000 car for Tesla means halving the cost of the basic Model S. A year ago, Musk said that “no miracles are required” to find such cost savings, but let’s do some math.

Musk’s battery costs already undercut everyone else’s. This is because, while other manufacturers including GM have started from scratch using “pouch” or metal rectangular cells—about the size of a puffed-up sheet of typing paper—Teslas have used off-the-shelf cells from Panasonic that have been produced at high volume, and thus more and more cheaply, for two decades. These “18650s” are cylindrical cells slightly larger a typical AA battery, and Musk says they cost him between $200 and $300 per kWh; the large-format cells used by manufacturers such as Nissan currently weigh in at $380 per kWh.

So lets assume $250 per kWh, the middle of Musk’s range, for Tesla. That means the battery in the entry-level 60 kWh Tesla S costs $15,000.

Now, Musk says he will cut costs further by building a “gigafactory,” a gigantic plant that will at once double the global production of lithium-ion batteries. That scale, he reckons, will shave another 30% off the cost per kWh. He also plans to add one-third more energy volume per battery by using larger cylindricals, known as 22700s, according to Navigant. Thus, Musk expects his battery costs to drop to $175 per kWh by 2017, making that same 60 kWh battery $10,500. But that cuts just $4,500 off the cost of the Model S; he needs another $30,000 or so.

Where will the rest of the savings come from? Navigant’s Sam Jaffe said Musk has “a good shot” at attaining them through economies of scale—a plunge in costs for the body, the suspension, the interior electronics, and so on—when the car is in large-scale production. “I don’t think they’ll be selling 200,000 of them in 2020, but even if they get to half that number, it will be one of the most successful new model launches in the history of the car industry,” Jaffe said.

How GM might get there

South Korea’s LG Chemical disclosed no details about how it will enable a 200-mile car, but several scientists told Quartz the company will probably start with a battery it produces for the plug-in Chevy Volt. This battery’s crucial positive electrode is a composite of nickel, manganese and cobalt (NMC) with a pinch of a crystalline structure called manganese spinel. The result is a car with a distance of about 37 miles, decent acceleration, and a 2014 price of about $34,000.

That is not good enough. But improvements in the NMC since the first Volt now eliminate the need for most or all the spinel. The result, say the scientists, is much greater energy density. In addition, Prabhakar Patil, the head of LG’s US-based research unit, told the Wall Street Journal this month that the company is banking on better management of the electric system and a reduction in other costs to bring down the price of the new battery. Skepticism persists that the price can come down low enough without a silicon anode–and no one thinks that LG has perfected one–but the scientists are withholding judgement.

The moment of truth is just two years away

Even if it gets a cheap battery, can GM stand toe-to-toe with Tesla? No one interviewed for this article thought so. It lacks the pizzazz, the style, and the engineering. “We just haven’t seen any incumbent carmaker that has been able to make a compelling plug-in car in the way that Tesla has,” said Navigant’s Jaffe.

This makes Musk the bettors’ favorite. Yet where Musk is gambling his company on the success of the Model 3, GM has options. It could ignore Tesla, and surrender the $30,000-$40,000 electric market, along with the technological crown that will go with it. It could surprise everyone and pull a winning, 200-mile automobile from the drawing boards of its design-and-engineering teams. It could also do neither and produce an entirely different, 200-mile car, one aimed at a lower demography, such as that served by its $14,000 Chevy Sonic (see this piece at Green Car Reports).

If it did the latter–a big if since it would upset all the assumptions regarding battery price and physics–GM would arguably leapfrog over Musk, into the biggest mass market of all. Some might call that an anticlimactic, even cowardly finish to the contest, with no direct and decisive bout between the celebrated Musk and the old stalwart. But, as Musk knows better than anyone in the industry, one does not always win by going with expectations.