St. Louis is becoming more diverse—just not in the black part of town

The Gateway to the West has grown more diverse, but you might not notice if you live north of the city’s iconic steel Arch. The predominantly black neighborhoods on this half of St. Louis remain segregated and neglected, far from the bustling immigrant communities flourishing in the traditionally white neighborhoods to the south.

The Gateway to the West has grown more diverse, but you might not notice if you live north of the city’s iconic steel Arch. The predominantly black neighborhoods on this half of St. Louis remain segregated and neglected, far from the bustling immigrant communities flourishing in the traditionally white neighborhoods to the south.

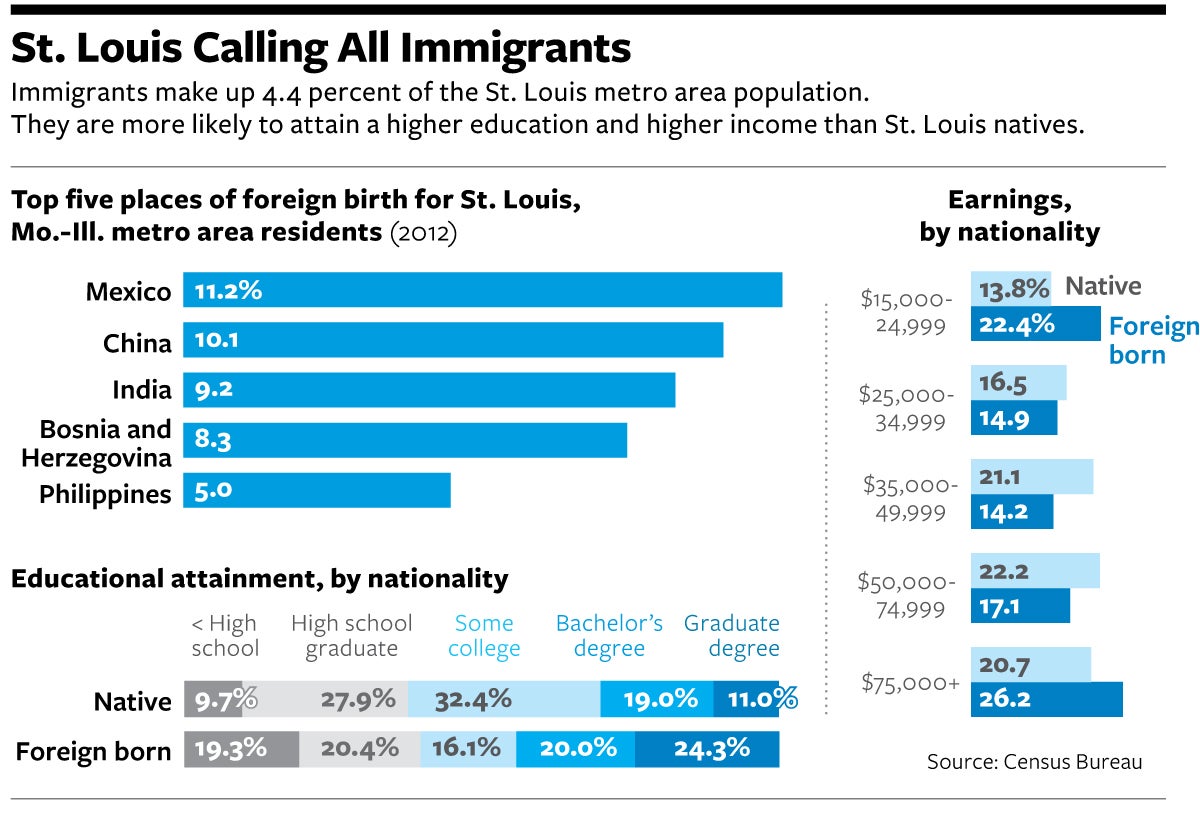

Newcomers from China, Bosnia, and Mexico have renewed derelict neighborhoods that suffered decades of decline. They’ve helped offset the city’s staggering population loss since World War II, when manufacturing jobs in the Rust Belt began moving overseas and white families moved to the suburbs.

Bosnian refugees have renovated aging homes around the Bevo windmill, built a century ago by the famous local brewer Anheuser Busch. Chinese families run teashops and restaurants in long-forgotten storefronts on Olive Boulevard. But even as the city puts resources into attracting more immigrants to revitalize the region, few of them venture north of Delmar Boulevard, where the city’s once-thriving black neighborhoods have turned to ruins.

This is where you can find most of the city’s 6,000 vacant buildings. The crumbling brick homes show what happens to a city that loses two-thirds of its population. Many of the city’s black families fled the decaying streets and moved to nearby suburbs—to mostly white communities like Ferguson.

These black families might have escaped the ghetto, but they could not escape racism. The riots that broke out in Ferguson this August reflect the simmering racial tension that has been building in the Rust Belt for a century. St. Louis ranked as one of the nation’s top 10 most racially segregated metro areas, according to a 2011 report by researchers at Brown University and Florida State University.

St. Louis city and county leaders had been focused on other problems, like how to bring more people and jobs to the region. In 2012, they launched an ambitious plan to make St. Louis the area with the nation’s fastest-growing immigrant population by 2020. They created the Mosaic Project, a public-private partnership with nonprofit groups and local business leaders that helps high-skilled immigrants find jobs in the growing biotech industry, among other recruitment efforts.

But not everyone is enthusiastic about these developments. Immigration only seems to benefit the white neighborhoods of south St Louis, says city Alderwoman Sharon Tyus, who represents a predominantly African-American ward with high unemployment and more than 300 empty homes.

“It’s frustrating to some people that they spend resources on immigrants when they could rebuild poor black communities,” she says, pointing out that her own neighborhood, Kingsway East, once attracted African-American doctors, lawyers, and teachers.

Only 6% of the city’s Asian and Hispanic residents live in the black part of town north of Delmar Boulevard, census data shows. Ten times as many have settled south of it.

St. Louis mayor Francis Slay says immigrants benefit the entire city, regardless of where they settle. Every business they open and every home they buy brings in more tax revenue, he told National Journal in a recent interview. But he acknowledges that the recent upheaval in Ferguson is a sign that government leaders need to work harder to address racial inequality.

“We need to do more,” Slay says. “We have major challenges in this region.”

There was a time when African-Americans prospered in St. Louis. The Ville, just north of the downtown, was the cultural heart of black St. Louis a century ago. African-Americans opened schools, hospitals, and businesses that boosted the local economy. Music legends like Tina Turner and Chuck Berry grew up here. So did Roscoe Robinson Jr., the first black four-star general in the US Army.

Many of these black families arrived in the city during the Great Migration, when thousands of African-Americans left the hostile South to find factory work in the Rust Belt. St. Louis factories produced everything from cars and subway trains to kitchen stoves and shoes. By 1950, St. Louis was the eighth largest city in the country, with a population nearing 900,000.

Barely 300,000 people live there now.

Racism played a role in that decline. White residents began fleeing to nearby suburbs, including Ferguson, as more and more African-Americans moved to St. Louis. These white communities made it nearly impossible for black people to follow them. Among other things, they used zoning laws and restrictive covenants to bar African-Americans from buying homes among them.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act eventually outlawed these practices. But more subtle forms of housing discrimination persist to this day. Real-estate agents across the country show black clients fewer homes for sale in white neighborhoods than they show to white, Hispanic, and Asian clients, according to a 2014 report by the Housing and Urban Development Department. In recent years, civil-rights attorneys have sued a St. Louis bank, a real-estate agency, and a suburban community for reportedly discriminating against African-American home buyers.

In 2001, HUD sued the suburb of Vinita Terrace after the local police marshal allegedly intimidated an African-American real-estate agent who was showing a house to one of her clients, who was also black.

Vinita Terrace, like Ferguson, is a St. Louis suburb that has changed in recent decades from a predominantly white community to a predominantly black one.

Albert Zadow, the village marshal at the time, was sitting in his patrol car across from the house that Fannie Simpson was showing to her client, according to the complaint. The court file said Zadow approached them and told Simpson he was writing her a ticket for illegally showing a house that had not yet passed an inspection, according to the complaint. When Simpson argued that the house had passed, Zadow allegedly said he would take her to jail if she didn’t take the ticket. When Simpson’s client complained, according to the complaint, Zadow stopped writing the ticket and put his hand on his gun.

Simpson took the ticket.

“Welcome to Vinita Terrace,” Zadow reportedly said, after handing Simpson the ticket and walking away.

Simpson and her client filed a discrimination complaint with HUD, and the Justice Department sued. The village agreed to settle the lawsuit, paying $16,500 to Simpson and $20,000 to her client, who had decided not to make an offer on the house. That house was later sold to a white family.

In 2011, Midwest BankCentre settled a lawsuit filed by the Justice Department, which accused the St. Louis bank of only opening branches in the city’s white neighborhoods to avoid lending money to African-American homeowners. Only 2% of the bank’s mortgage loans financed purchases in the north side of the city, according to the complaint.

These subtle forms of discrimination have made it hard for African-Americans to prosper in St. Louis, says Alderwoman Tyus, who spends a lot of her time urging the city to board up empty buildings and cut the grass. The city owns eight homes on her street, but Tyus says it’s unlikely that immigrants or white families will move in. And it bothers her that Asian immigrants will open corner stores and restaurants in her community, but they won’t hire people who live here, or even live here themselves.

“Nobody wants to live next to black people,” she says.

This post originally appeared at National Journal. More from our sister site:

What a Getty photographer captured before he was arrested in Ferguson