Australia has a de facto second currency: frequent flier miles

Of all the reasons consumers have to be wary of corporate loyalty programs, this may be the biggest: When a company starts to lose value, so too do its loyalty points.

Of all the reasons consumers have to be wary of corporate loyalty programs, this may be the biggest: When a company starts to lose value, so too do its loyalty points.

A prominent example: Australia’s Qantas Airlines, whose frequent flier program has been a strong play for the company. In fact, it was the only bright spot in its annual earnings report last week: The company reported a $2.6-billion yearly loss overall, but its loyalty program, which counts more than 10 million members (nearly half Australia’s total population), posted a record profit in its fifth consecutive year of double-digit earnings growth.

There are pros and cons to this setup. Frequent passengers on Qantas get a lot more than just miles for flights, including golf club privileges and an “online mall,” in which fliers can spend points gleaned from purchases at retailers such as Apple, eBay, Neiman Marcus and Selfridges (the retailers buy the points from Qantas to lure customers to their sites). Neiman Marcus, for instance, offers five points for every $1 spent on its wares, while Apple and eBay offer two points for every $1. There are also a lot of bonuses for retailers, like consulting services, data mining and gift card programs.

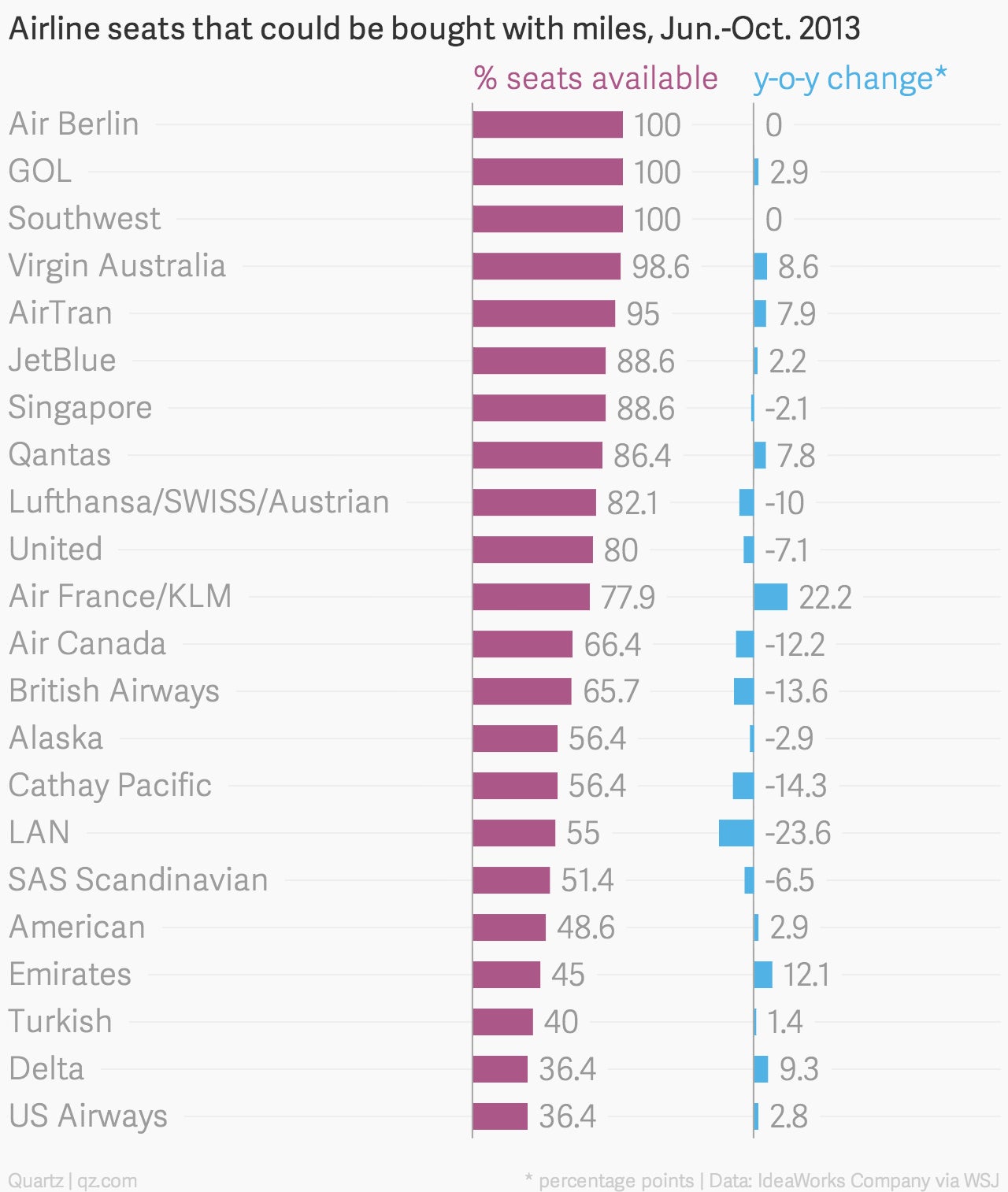

But just as a central bank can devalue its currency when the economy is in trouble, a loyalty-heavy airline can devalue its points. In the face of razor-thin margins, many airlines have been doing just that. As they’ve spent more on luring affluent fliers with luxurious cabins and amenities, one way of containing costs has been to restructure awards programs. United Airlines and Delta, for instance, have ratcheted up the miles needed to buy awards tickets and made it harder to achieve elite status. Airlines such as Delta have also severely limited their ration of rewards seats. Below are results published in the Wall Street Journal of a test of seat availability across airlines last year.

For its part, Qantas has responded to financial troubles by floating the idea of selling its frequent flier business, and in July it revamped its points system so that fliers earn points based on their ticket class, rather than the distance flown. In other words, the biggest rewards go to the people who pay the most.

Qantas has said the changes create a “fairer, more simplified program. ” Loyal followers disagree.

Wow – @QantasAirways . Not sure how punishing your most loyal customers and frequent flyers helps you save $252m. #frequentfailer #qantas

— Nick Condon (@nickcondon) March 27, 2014

QANTAS continues it’s strategy of alienating passengers by reducing frequent flier points for cheaper fares. #qantas #expassenger

— Gary Newcombe (@newkstar) March 27, 2014

There’s at least one way for frequent fliers to push back. Just as currency holders might ditch a plummeting currency, Qantas points holders could dodge long-term devaluation by quickly cashing out.