Why caring about style doesn’t make you shallow

The fashion images that bombard us in the 21st century are not always pretty. Glossy magazines are filled with pages designed to compel us to buy beyond our means. Fast fashion moves at a pace catastrophic for the environment and many of its workers. And the red carpet—once a parade of Hollywood glamour—is now mostly a boring showcase for designer sponsorships. (Sarah Silverman excepted.)

The fashion images that bombard us in the 21st century are not always pretty. Glossy magazines are filled with pages designed to compel us to buy beyond our means. Fast fashion moves at a pace catastrophic for the environment and many of its workers. And the red carpet—once a parade of Hollywood glamour—is now mostly a boring showcase for designer sponsorships. (Sarah Silverman excepted.)

Today, another New York Fashion Week is officially upon us. Then London, Milan, Paris, and so on. The fashion cycle can be punishing to follow, and harder to love.

Clothes, however, are another matter. If fashion is like a fancy restaurant, clothes, in a sense, are like food: a human necessity, no matter how you serve it. Just as food nourishes us, our clothing protects us. And like a comforting family recipe or a Proustian madeleine, clothes can sometimes communicate what isn’t said aloud—whether across cultures, generations, or just across a room.

It is this clothing-inspired communication and interaction that’s explored in the interviews, essays, and art projects that fill the 500-plus pages of Women in Clothes, a new book by Sheila Heti, Heidi Julavits, and Leanne Shapton.

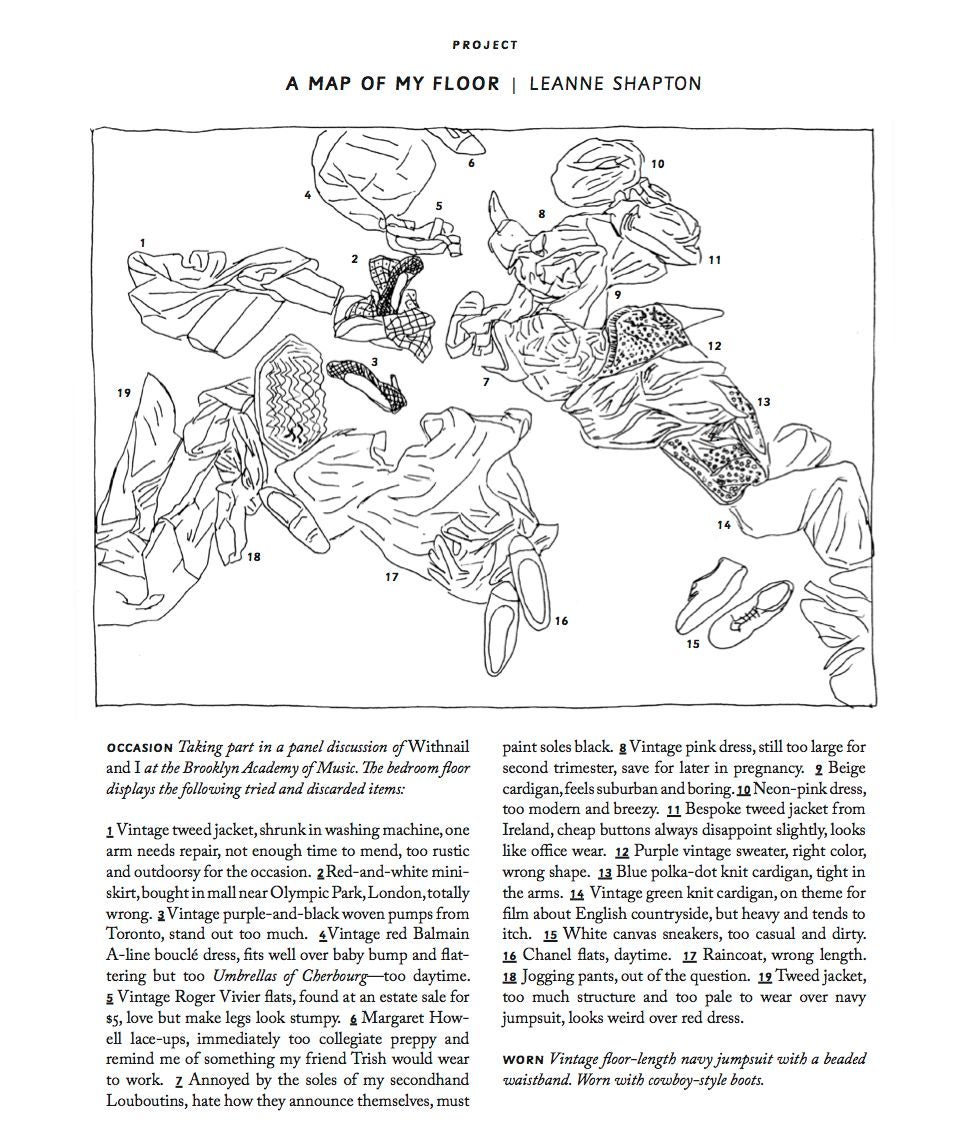

Unlike many books about style and fashion, Women in Clothes doesn’t cast judgment and it isn’t prescriptive. Its multimedia exploration of identity, clothing, dressing, and style plays out through illustrations of stains, shopping diaries, documentary-style photographs of women’s garment collections, and diagrams of the clothes left behind on a floor after getting dressed. It’s also filled with essays, conversations, surveys, and interviews on making, wearing, and observing clothes.

“We were interested in how weird and funny and heartbreaking it all is,” said Shapton. “We’re not trying to sell anyone on anything.”

Heti, Julavits, and Shapton—already acclaimed authors and editors—reached out to their personal and professional networks for contributions to the book, pulling together a raft of contributors that would make for a pretty daunting cocktail party. (Think Girls creator Lena Dunham, Sonic Youth front-woman Kim Gordon, artist Cindy Sherman, Bad Feminist author Roxane Gay, and National Book Award finalist Rachel Kushner, to name a few.) They also expanded their search via social media, ultimately reaching over 600 women around the world. Across its diverse set of contributors, the book maintains a refreshingly confessional, vulnerable, intimate, and compassionate tone.

I spent the bulk of my holiday weekend with Women in Clothes. As I braced myself for New York Fashion Week—an intensely image-driven setting that invites snap judgments—Women in Clothes reminded me that thinking about style can be far from shallow:

Clothes as memory

Adult Magazine (NSFW) founding editor Sarah Nicole Prickett tells the story of falling in love with her now-husband through what she wore, and Toronto Star columnist Heather Mallick offers a short, evocative note about a woman in a red polka-dotted skirt with a pistachio ice cream cone she saw on the subway as a child: “I stared in awe and thought, ‘One day I will move to the city and live in my own apartment and dress like her.'”

Clothes as connector

Various contributors sent photos of their mothers from before they had children, and captions about what they see in the images (here’s mine). The editors gathered short transcripts of exchanges that ensued after one woman complimented another’s clothing. And there’s a candid conversation between the women of the podcast “Black Girls Talking” on the power of community among women of color, especially when it comes to finding one’s style and embracing natural hair.

Clothes as story

Thessaly La Force‘s “My Outfits” titles a dozen of her own looks—”Princess Di at a grunge concert,” for example, included a long pleated skirt, ballet flats, a large sweater, and a black beanie. Lena Dunham talks about communicating through clothes: “I do try to let people know I am with them, I am really with them, based on what I wear to meet them.” And Leanne Shapton shares the strangeness of new motherhood in a story about giving into her covetousness of another woman’s dress.

Clothes as a piece of the globalized economy

The 18-year-old Bangladeshi factory worker Reba Sikder shares a terrifying first-person account of the garment factory collapse at Rana Plaza. And the Vietnamese immigrant Ly Ky Tran tells of sewing bow ties on a family assembly line in her Brooklyn apartment as an elementary-schooler in the 1990s: “We literally thought all the other kids were doing the same thing,” she recalls.

Clothes as identity

Umm Adam, a Muslim homemaker writes about covering her beautiful body with a jilbab and hijab with a level of self-assured confidence and dignity commonly associated with Beyoncé. Transgender author Juliet Jacques talked about shopping for dresses as she transitioned to a woman, and a handful of women shared hilarious and endearing admissions about idiosyncratic habits: “I often tuck my shirt into my underwear,” admits Audrey Gelman.