These are the websites where hackers flip stolen credit card data after an attack

The Home Depot data breach uncovered last week may be one of the largest cases of mass credit-card compromise ever. Data from every card used in a transaction at any US Home Depot store since late April or early May could be in the hands of hackers, who infiltrated company systems using malware similar to what was used in a 40 million-card theft from Target in December. The number of cards stolen from Home Depot is not known, but might exceed the Target total.

The Home Depot data breach uncovered last week may be one of the largest cases of mass credit-card compromise ever. Data from every card used in a transaction at any US Home Depot store since late April or early May could be in the hands of hackers, who infiltrated company systems using malware similar to what was used in a 40 million-card theft from Target in December. The number of cards stolen from Home Depot is not known, but might exceed the Target total.

After such a heist, stolen cards start showing up for sale on the many illegal online markets that deal in other people’s plastic. Cards from the Home Depot breach were first noticed at a known dealer called Rescator. In the past year, Rescator has been the principal vendor in a number of large-scale breaches, including the Target infiltration, the Sally Beauty break-in, the P.F. Chang’s job, and the Harbor Freight caper, according to computer security reporter Brian Krebs, who first broke the Home Depot story.

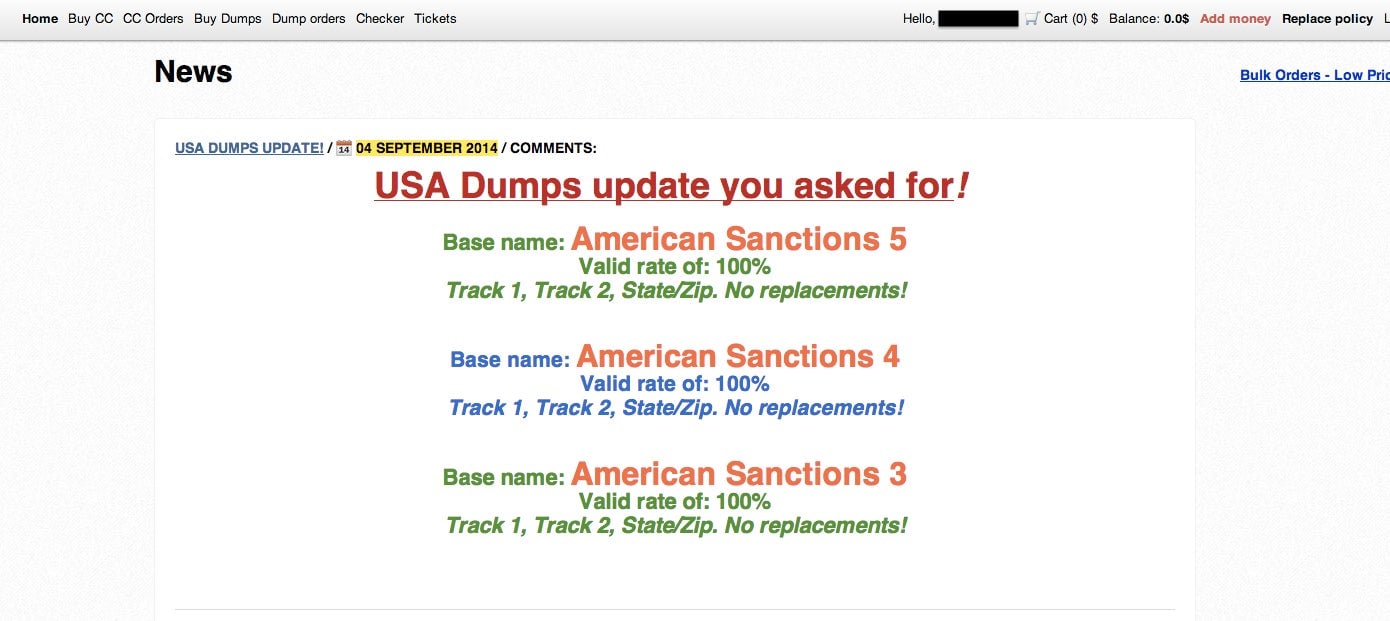

Rescator looks like a Web 2.0 site thrown together by a programmer with a decent sense of User Experience design and not much discretion regarding brightly-colored fonts. The database of stolen cards can be searched by a number of inputs, including zip code and Bank Identification Number—the first six digits of a credit card that are uniquely associated with the institution that issues it.

Once a “carder” makes a purchase via Bitcoin, Western Union, or any of the various electronic payment platform the site accepts, he or she receives a file that contains the credit card’s magnetic strip data, which can then be loaded onto a forged card that can be used in person at stores.

Rescator is one of hundreds of sites devoted to selling stolen credit cards, many identifiable via cursory Google searches. Krebs profiled in-depth one such site, known as “McDumpals,” in June. Krebs’ investigations also have identified an individual responsible for Rescator and some of its “mirror” sites—pages that run copies of the same website in case one server is shut down by hackers or by the government.

Rescator is run from servers in Russia, so the United States is powerless to seize or block the page, according to Mark Lanterman, an investigator for Computer Forensic Services, a private information security firm.

Unlike the now-defunct Silk Road and other “dark net” marketplaces that can be found only at obscure URLs accessed from special web browsers, Rescator and many other card thievery sites are accessible to ordinary web browsers and have readable web addresses. This no doubt is a tradeoff for dealers in illicit plastic, sacrificing the greater anonymity of the dark web for the increased visibility—and, perhaps, business—provided by the Internet that’s there for the rest of us.