When it comes to a China growth slowdown, bad news is actually good news

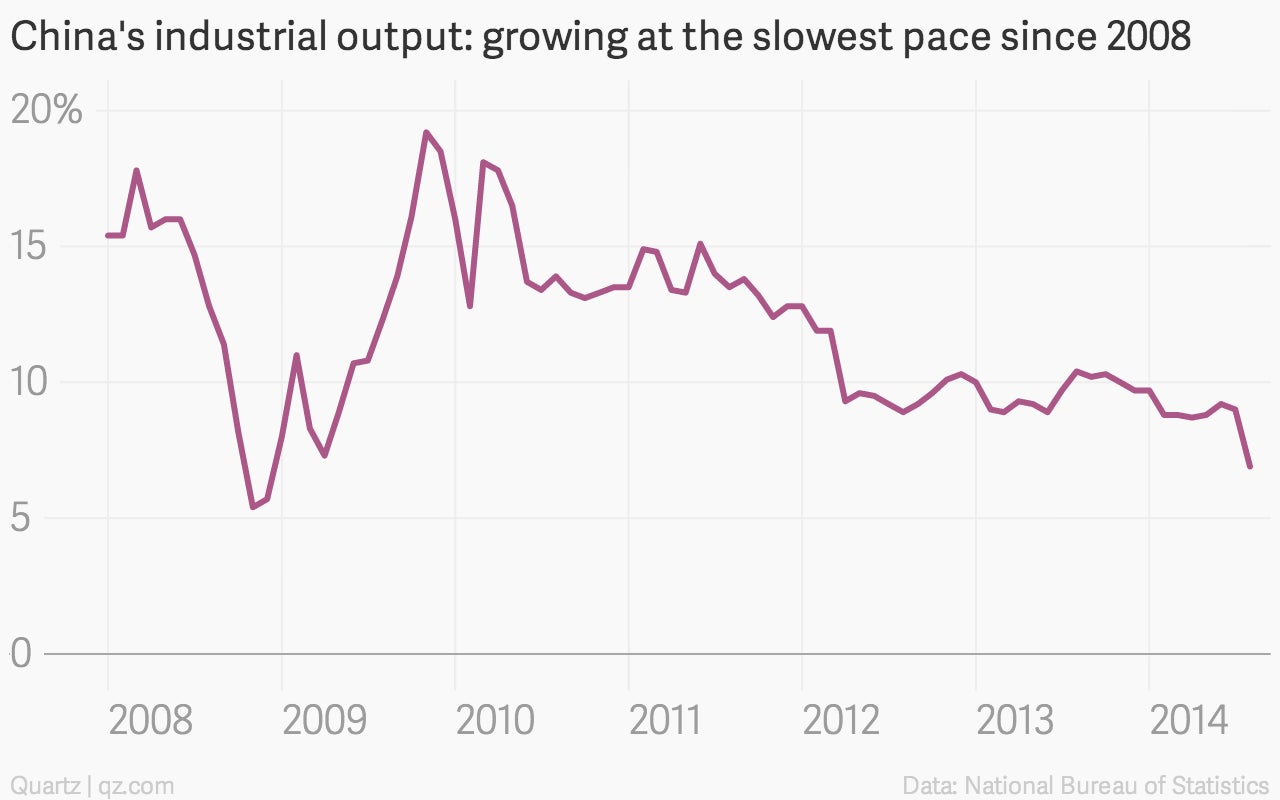

News that Chinese factories are pumping out goods at the slowest pace since the height of the global financial crisis sent share prices and commodities reeling today. And it wasn’t a blip: power generation fell 0.6% versus Aug. 2013, down from 5.3% growth in July.

News that Chinese factories are pumping out goods at the slowest pace since the height of the global financial crisis sent share prices and commodities reeling today. And it wasn’t a blip: power generation fell 0.6% versus Aug. 2013, down from 5.3% growth in July.

Finally—some cheery Chinese economic news! No, really. The fact that even as the housing market has tanked, premier Li Keqiang (who is thought to head up China’s economic planning) and central bank chief Zhou Xiaochuan haven’t added new stimulus measures is heartening. The “tolerance level for short-term pain seems to have jumped up by another big notch,” Wei Yao, an economist at Société Générale, wrote in a note this morning.

Of course, not everyone thinks such “tolerance” is a good thing.

“This is a pretty important wakeup call that [China’s leaders] need to do more,” Helen Qiao, economist at Morgan Stanley, told Bloomberg, adding that China can still hit its 7.5% GDP growth target ”if they roll out more easing measures starting from now.”

Li and Zhou face a dilemma. They can boost GDP with cheap money yet again, piling on still more debt and postponing much-needed reforms. Or they can limit the size of China’s corporate debt, accepting that growth will slip—almost certainly below the promised 7.5%, and possible quite a bit lower—but making reforms possible.

To recap recent history, the Chinese government combatted the global financial crisis with a flood of cheap loans from state-owned banks. Even as it began slowing the growth of official lending in 2010, the explosion of off-balance-sheet financing—a.k.a. “shadow banking“—kept the economy humming.

China’s closed financial system means the central bank makes money cheap not by lowering rates but by forcing banks to lend—usually to other state-backed companies—whether the recipients need capital or not. These companies in turn built new factories, profited by re-lending to more credit-starved private entities, and speculated on the property market. To the extent anyone thought much about it, the assumption was that global demand would pick up soon, boosting the Chinese economy enough for companies to repay their borrowings.

That global economic revival didn’t happen, though.

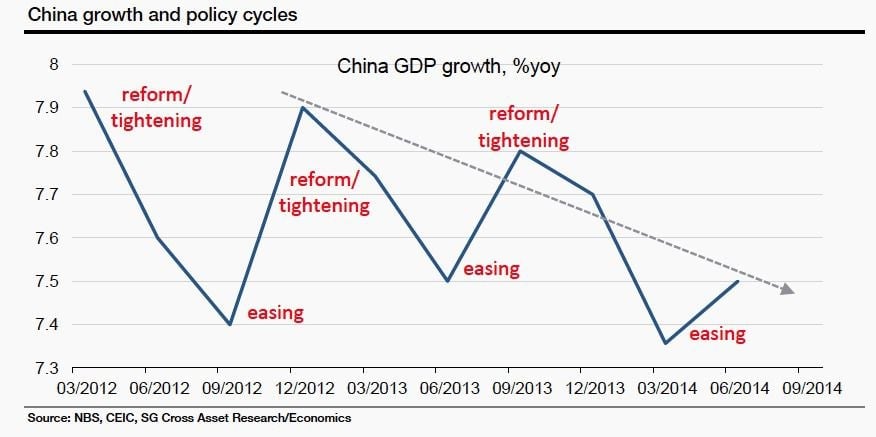

Drowning in debt, hundreds of thousands of Chinese companies now depend on a steady flow of new loans to pay interest on old ones. That’s why each shadow-banking crackdown makes the economy slow sharply, as you can see in this chart from SocGen:

This chart highlights another subtle but crucial point. It’s impossible for China to reform its financial system—most notably, liberalizing interest rates—while keeping zombie companies alive with easy money. But China needs to implement these reforms, which will transfer wealth from the state sectors to households, not only to keep the economy growing, but also to avoid a financial collapse.

For Morgan Stanley and anyone else taking the short view, the choice facing Li and Zhuo is a no-brainer—ease now, worry about the consequences later. Eventually, though, that’s bound to lead to either a financial crisis or a Japan-like lost decade (or two). This hint that China’s leaders might let the economy take its blows now means they just might avoid either of these economic beat-downs in the long term.