Facebook’s “real name” policy isn’t just discriminatory, it’s dangerous

Facebook has begun vigorous enforcement of its “name policy,” requiring all users of the social network to provide their real names—those “listed on your credit card, driver’s license or student ID.” The policy is not new—Facebook has long asked for users’ “real names” at registration—but it has come under new fire after Facebook disabled the profile of San Francisco LGBT activist and drag queen Sister Roma last week, forcing her to post under her legal name “Michael Williams.”

Facebook has begun vigorous enforcement of its “name policy,” requiring all users of the social network to provide their real names—those “listed on your credit card, driver’s license or student ID.” The policy is not new—Facebook has long asked for users’ “real names” at registration—but it has come under new fire after Facebook disabled the profile of San Francisco LGBT activist and drag queen Sister Roma last week, forcing her to post under her legal name “Michael Williams.”

The social media outrage was almost immediate. An online petition on Change.org demanding Facebook change its policy has already garnered 18,300 signatures. Today, Facebook representatives met with members of the drag and LGBT communities in San Francisco. Regardless of the outcome of today’s meeting at Facebook HQ, (I’m pessimistic considering the protesters only got to meet with Facebook’s “PR and Pride” teams), these people’s lives have already been impacted by Facebook’s enforcement policy.

I should know. I haven’t been able to use my personal profile on Facebook since Aug. 27 when it was shut down.

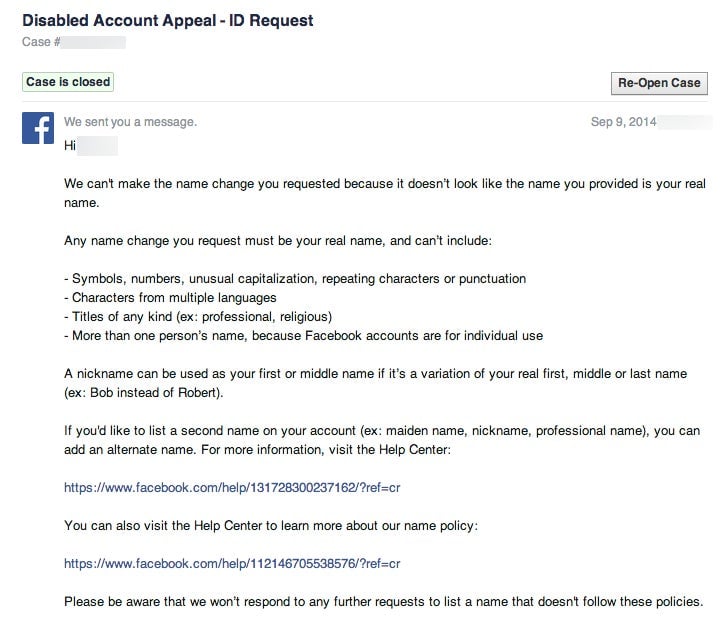

Much like Sister Roma, Facebook told me that their “systems indicated that [my] account may not be authentic based on a variety of factors” and I was blocked from Facebook on Aug. 26; I would have to submit a “scanned image or digital picture” of a “government-issued ID” (pursuant to their updated ID policy) to the Facebook Help and Support Center in order to regain access. After changing the name on my profile to match the name on my ID, a representative for Facebook twice referred me to the name policy about “titles of any kind,” implying that “Yitz”—my Hebrew name, which I have used since conversion to Judaism nearly 15 years ago—was a “religious title.” After sending in two additional pieces of supplementary ID reflecting my new name (the one on all of my IDs), I was warned that Facebook’s Support Center would simply “not respond” to me any longer. (Update: To clarify, my profile was re-enabled with my birth name after sending Facebook my personal identification information. However, given that I have used my Hebrew name for over a decade, I could no longer interact on Facebook with a community who didn’t recognize me. I took down my profile photo as a result.)

The impact of Facebook’s name policy is not limited to the LGBT or faith-based community. Young job seekers have long turned to modified forms of their names to hide personal profiles from prospective employers, not surprising considering that 70% of hiring managers in 2010 reported rejecting candidates (pdf) due to information obtained via social media. Some Facebook users reported being locked out even when using their legal names: Chase Nahooikaikakeolamauloaokalani Silva of Hawaii had his middle name shortened to “N” when Facebook declared his given name to be fraudulent (too many “repeating characters,” maybe?). One San Francisco-area therapist told CNN he uses pseudonymity to prevent his patients from seeing his personal social profile. Numerous victims of abuse and bullying have posted in vain to Facebook’s Help and Support Center asking to have their legal names and birthdates removed from the eyes of their abusers, leading one user to comment that Facebook “does not care” about users’ safety. In fact, no one seems to be immune: even Lady Gaga had to “merge” her real name with her 67-million-like fan page.

Today’s the big day. Meeting with @Facebook. We’re representing a million users with “fake” names with a million valid reasons. #MyNameIs

— Sister Roma (@SisterRoma) September 17, 2014

To Facebook’s credit, a ”real name” policy can help to reduce trolling and cyberbullying, since users are often disinhibited when protected by a veil of perceived anonymity. However, as Google noted in July, after reversing its three-year name policy on Google+, such a policy can lead to “unnecessarily difficult experiences” for some users.

@stevekerns @ylove If @facebook changes my name without my consent it will cause me problems w my biz but ALSO serious emotional damage

— Gavriela Rivka (@sageblessing) September 17, 2014

Facebook has a responsibility to address the existential issues it has placed on some of its users. “No response” is not an answer. Putting users’ lives in danger, as is the case with abuse victims and some LGBT users, is unacceptable conduct for any social network. For Facebook to enforce such a policy only months after having allowed gender-variant users to choose from dozens of gender options is incongruous at best and hypocritical at worst. If the site wants to rely so heavily on its users’ data for its paid targeting and advertising products, it must provide a platform on which users are comfortable and willing to share that data.

Facebook’s “real name” policy is now creating users who are afraid of being outed, victimized, fired, or otherwise negatively impacted—a far cry from the “safe community” Facebook espouses to be.