What will become of Harris Tweed if the Scots vote for independence?

While many epicures watching the vote for Scottish independence are wondering what will become of their favorite peaty Scotch whisky, those with refined sartorial tastes might be more concerned about their tartans and tweeds.

While many epicures watching the vote for Scottish independence are wondering what will become of their favorite peaty Scotch whisky, those with refined sartorial tastes might be more concerned about their tartans and tweeds.

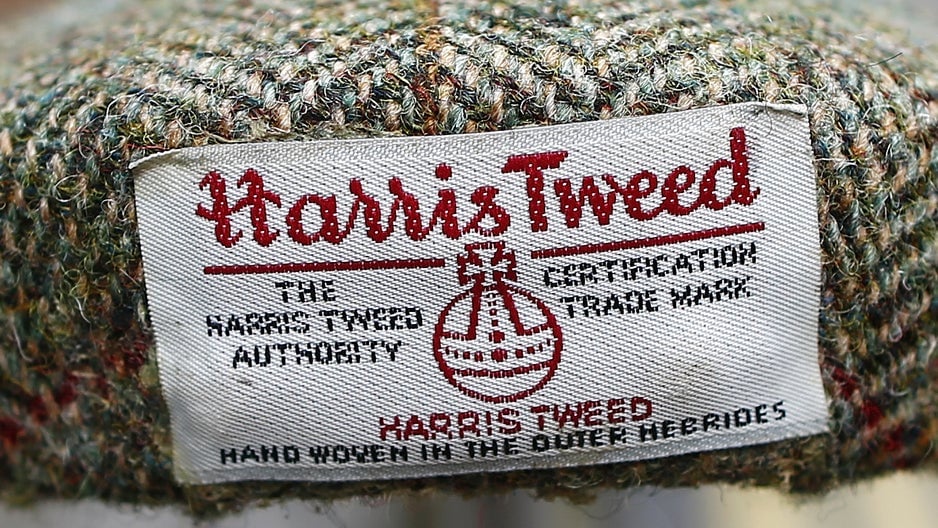

Among the most distinctively Scottish of Scottish textiles is Harris Tweed, a robust, multicolor-flecked woven wool that’s as origin-specific as Champagne, Parmigiano-Reggiano, or yes, Scotch.

Harris Tweed, which has been used in natty coats and jackets by designers such as Paul Stuart and Brooks Brothers, as well as more contemporary looks by Duckie Brown and Joseph Altuzarra, can only be produced by the residents of Lewis and Harris, an arctic wind-whipped, boulder-strewn isle off Scotland’s west coast, in the outer Hebrides.

Those residents are a hearty, self-reliant bunch, and when Quartz spoke with Kathy Macaskill, who manages one of Lewis and Harris’s three Harris Tweed mills, she said “independent” was the way she thought her fellow islanders were voting. She wouldn’t reveal which way she herself voted, but sounded a little skeptical of the UK Parliament’s control over the region: ”We’re so far from London, and they make a lot of rules and regulations that don’t take us into consideration, being a remote area.”

That said, it’s a 1993 Act of Parliament (pdf) that designated Harris Tweed’s home-woven, Hebridean heritage by “preventing the sale as Harris Tweed of material which does not fall within the definition.” David Hudson, the North American agent for Carloway Mill—one of the three that produces Harris Tweed—says he’s concerned about the referendum. “Changes like this don’t come very often within the textile industry,” said Hudson. “The only thing that I can relate it to, and it’s really a very broad relation, is back in the late 80s, early 90s, the breakup of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. I used to do a lot of business with their textile industry and it was one country—Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro. I was working with several mills when the Berlin Wall came down. Within six months, all the mills closed because of the breakup of the country. There was a war there; a lot of people were scared to do business there.”

Hudson said he doesn’t anticipate similar turmoil in Scotland, but is apprehensive nonetheless. “My hope is that nothing will change.”

Alan Bain, a co-owner of the Carloway Mill and the chairman of the American Scottish Foundation, says he’s torn on the issue. “If Scotland is an independent country, the Scottish government may be inclined to promote its global brands, which are textiles generally,” he said. A weaker British pound could also make Harris Tweed cheaper for overseas customers—no small attraction for a pricey fabric with a respected pedigree. On the the other hand, as a businessman whose retirement fund is impacted by the currency’s strength, Bain naturally doesn’t want to see it tank. And then there’s the question of who will administer the parliamentary act protecting Harris Tweed.

Ultimately, whether the tweed comes from an independent Scotland or not, Bain said, the fabric itself won’t change: ”People who love Harris Tweed are going to love it regardless.”