Why people stay where they are

From conquering the Western frontier to the great movement to the suburbs, nothing has been more central to the American experience than mobility—the ability to seek out new places offering better homes, more space, better jobs and more economic opportunity.

From conquering the Western frontier to the great movement to the suburbs, nothing has been more central to the American experience than mobility—the ability to seek out new places offering better homes, more space, better jobs and more economic opportunity.

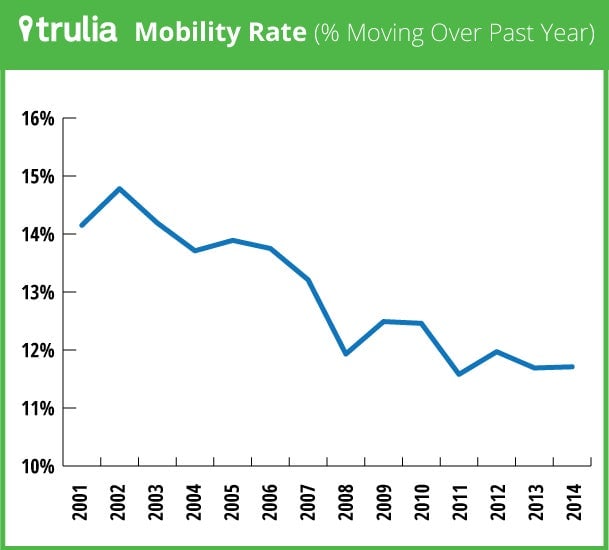

But according to a growing body of data, this long-coveted mobility appears to be slowing substantially. According to US Census data, the share of Americans who move each year fell from more than 20% during the 1950s and 60s to just 11.7% last year, which is just about the lowest level since such statistics have been collected. The chart below, produced by Trulia and based on the Census data, shows the downward mobility trend since 2001.

Several explanations have been offered for this slowdown in mobility, from the declining economic payback of moving for a job to decreasing housing affordability in some places to people being locked in place with homes they cannot sell.

While the desire to move to new and better places remains deeply ingrained in American culture, the reality is there are many more stayers than movers.

All of which raises the question: Why do so many people stay where they live and what are the main reasons they do so?

• • • •

The Atlantic Media/Siemens State of the City poll provides some useful evidence. My Martin Prosperity Institute (MPI) colleague Charlotta Mellander dug into the data (performing a statistical technique called a logit regression) to zero in on the factors that are associated with why people choose to stay where they live.

Some of the factors are rather obvious. Older people are more likely to stay where they are. This is in line with Census data that also shows mobility declines with age. Homeowners are also more likely to stay, as are as suburbanites and rural residents. As my colleague John Metcalfe has previously reported, the young, the poor, and those who already live in cities are most likely to say that they are likely to move in the near future.

But Mellander’s analysis turns up two more curious findings. While we would expect people in communities with higher unemployment and fewer good jobs to be more likely to move, her analysis finds the opposite. People in areas with fewer good paying jobs were more likely to say they are staying put. One explanation may be that people in communities with more economic distress and lower levels of satisfaction lack the resources to move and may essentially be stuck in those places.

Interestingly, while the US Census identifies housing as the main reason more than half of Americans move, our survey suggests that the intent to stay is not necessarily tied to either the affordability or quality of housing. Neither of these were statistically significant in Mellander’s analysis. Taken together, this would seem to imply that the decision to stay is tied less to quality or affordability of housing itself, and more to the quality of the neighborhood or community.

• • • •

If movers are driven by economic opportunities and incentives, then stayers often place a higher value on family and social ties and the quality of their neighborhoods. Indeed, a 2008 Pew survey found that stayers “overwhelmingly stay because of family ties.” The majority of stayers had at least a half dozen extended family members within an hour’s drive, according to the study, while movers had far fewer; one in four had none. Stayers were much more likely than movers to feel a sense of belonging to their community and to view their neighborhood as a good place raise children. Indeed, a 2007 study found that the happiness derived from seeing friends is worth an additional six figures of income.

Deeper understanding of the role of social ties and quality of place on those who stay comes from a large-scale survey of more than 20,000 Americans conducted by the Gallup Organization. The survey asked residents not just about their decisions to stay or move, but about their level of emotional attachment to their communities and the characteristics of their communities that matter most to them. Mellander and I, along with Kevin Stolarick, conducted a detailed statistical analysis of these data to identify precisely which factors matter to stayers in a study. (“Here to Stay“ was published in the Journal of Spatial Analysis).

The main reasons why stayers stay, according to our analysis, revolve around social relationships and quality of place: the ability to meet people and make friends; the quality of public schools; and the overall physical beauty and quality of a neighborhood. These were much more important than economic factors like the availability of job opportunities or the perception of future economic conditions, which our analysis found not to be statistically associated with why people stay.

An update of this Gallup survey supported by the Knight Foundation and expanded to more than 40,000 Americans reinforces these findings. The study concluded that “three main qualities attach people to place: social offerings, such as entertainment venues and places to meet, openness (how welcoming a place is) and the area’s aesthetics (its physical beauty and green spaces).” This survey found that these community factors were much more important to a person’s emotional attachment to their community than their age, marital status, ethnicity, education, ethnicity, or occupation. Ultimately, the survey found that what attaches Americans to their communities tends to be consistent across communities, and is mostly unaffected by the up and downs of the economy.

• • • •

In my book Who’s Your City?, I divided people into three broad categories: the mobile, the stuck and the rooted. We tend to focus on the first two: the mobile, who can pick up and move to opportunity, and the stuck, who lack the resources to leave where they are.

But we cannot forget about the rooted—those who have the means and opportunity to move, but choose to stay.

In an intriguing essay on this site back in 2011, Julie Irwin Zimmerman shed some light on this ill-understood group. As a Cincinnatian, she wrote, “I’ve begun to understand why so many natives stay put. They’re not stuck. They’re content.” Zimmerman cited her city’s affordable cost of living, reasonably stable economy and small-town feel. “The ties people have to their families and neighbors here are worth forgoing many of the economic opportunities other cities may offer,” she wrote.

Too many of us have a tendency to think the grass is greener elsewhere, and in doing so, we tend to discount the enduring value of our ties to others and to our communities. Developing a greater understanding of how we become more deeply connected to and rooted in our communities is key enhancing the quality of the lives we lead and the places where we live.

This post originally appeared at CityLab. More from our sister site:

A death in Central Park raises real questions about bicyclist behavior