We found mankind’s first computer technology in an ancient Greek shipwreck and robots are going back for more

One of the world’s most mysterious artifacts was plucked from the Mediterranean sea in 1901, when a shipwreck discovered by Greek sponge divers off the coast of Antikythera yielded not just magnificent works of art but also what archeologists suppose is evidence of mankind’s earliest “computer”—an instrument dating to the era of Archimedes, with gears and dials for calculating solar and lunar cycles. What little they know about this device, dubbed the Antikythera mechanism, is intriguing enough to warrant high hopes that a modern-day exploration of the shipwreck will uncover additional fragments of the object, or other evidence of ancient innovation.

One of the world’s most mysterious artifacts was plucked from the Mediterranean sea in 1901, when a shipwreck discovered by Greek sponge divers off the coast of Antikythera yielded not just magnificent works of art but also what archeologists suppose is evidence of mankind’s earliest “computer”—an instrument dating to the era of Archimedes, with gears and dials for calculating solar and lunar cycles. What little they know about this device, dubbed the Antikythera mechanism, is intriguing enough to warrant high hopes that a modern-day exploration of the shipwreck will uncover additional fragments of the object, or other evidence of ancient innovation.

Scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the Hellenic Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities are at the site right now for a month-long excavation, the first one approved by the Greek government since 1976 (when Jacques Cousteau explored the wreck). This time, they’ve got 3D-mapping capabilities, autonomous robots, and a very special diving suit. The technology—much of it used elsewhere for more prosaic purposes—has revolutionized underwater treasure-hunting since Cousteau’s time.

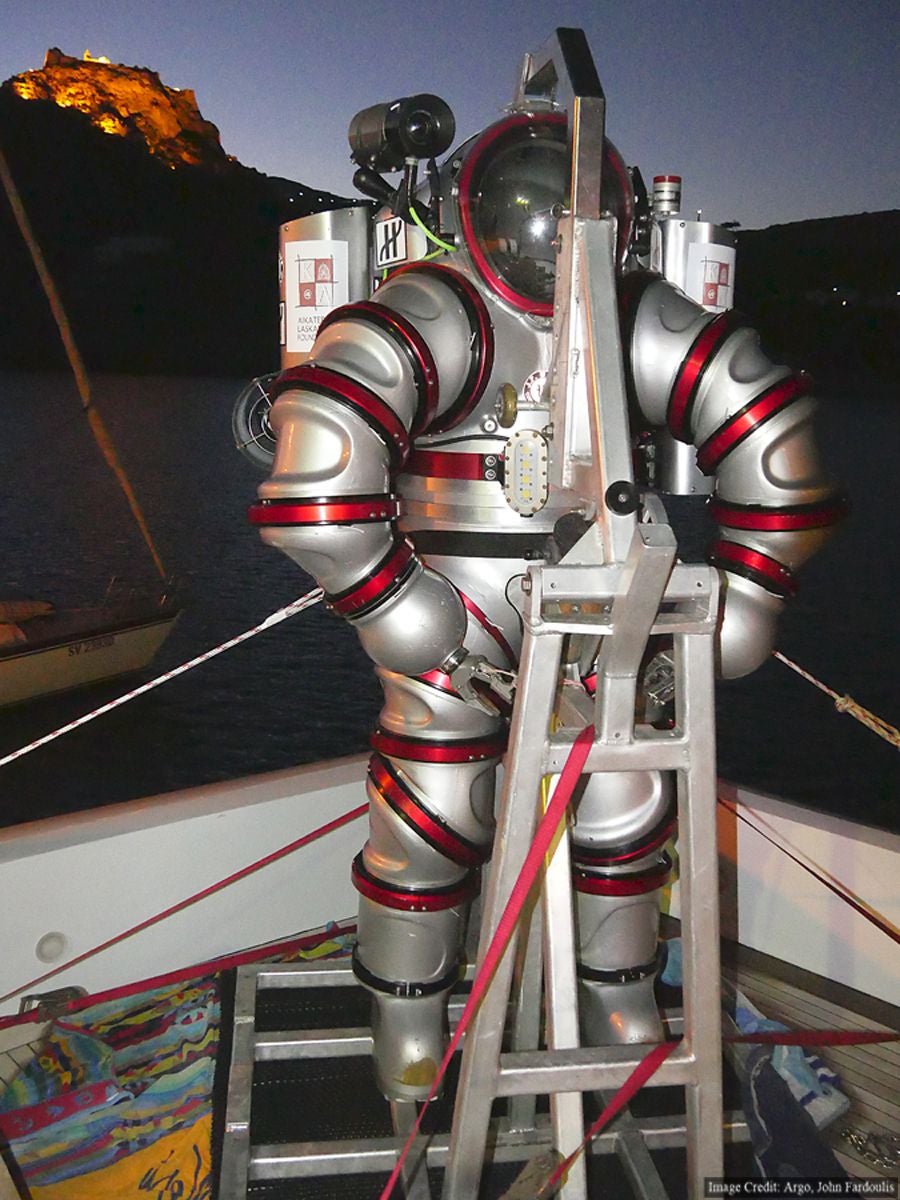

First, the Exosuit: an atmospheric diving system that allows its wearer to descend as far as 300 meters, or a thousand feet, below the sea surface and stay there for hours (50, if need be) without needing to decompress before returning to the surface. This allows the diver to walk around the Antikythera wreck, which lies a little under 200 feet deep, without experiencing any change in atmospheric pressure or even getting wet. Full specs (PDF) are available from the suit’s manufacturer, Nuytco. WIRED reports that the suit has been used by workers in New York to repair the city’s pipes and in Dubai to inspect oil pipelines.

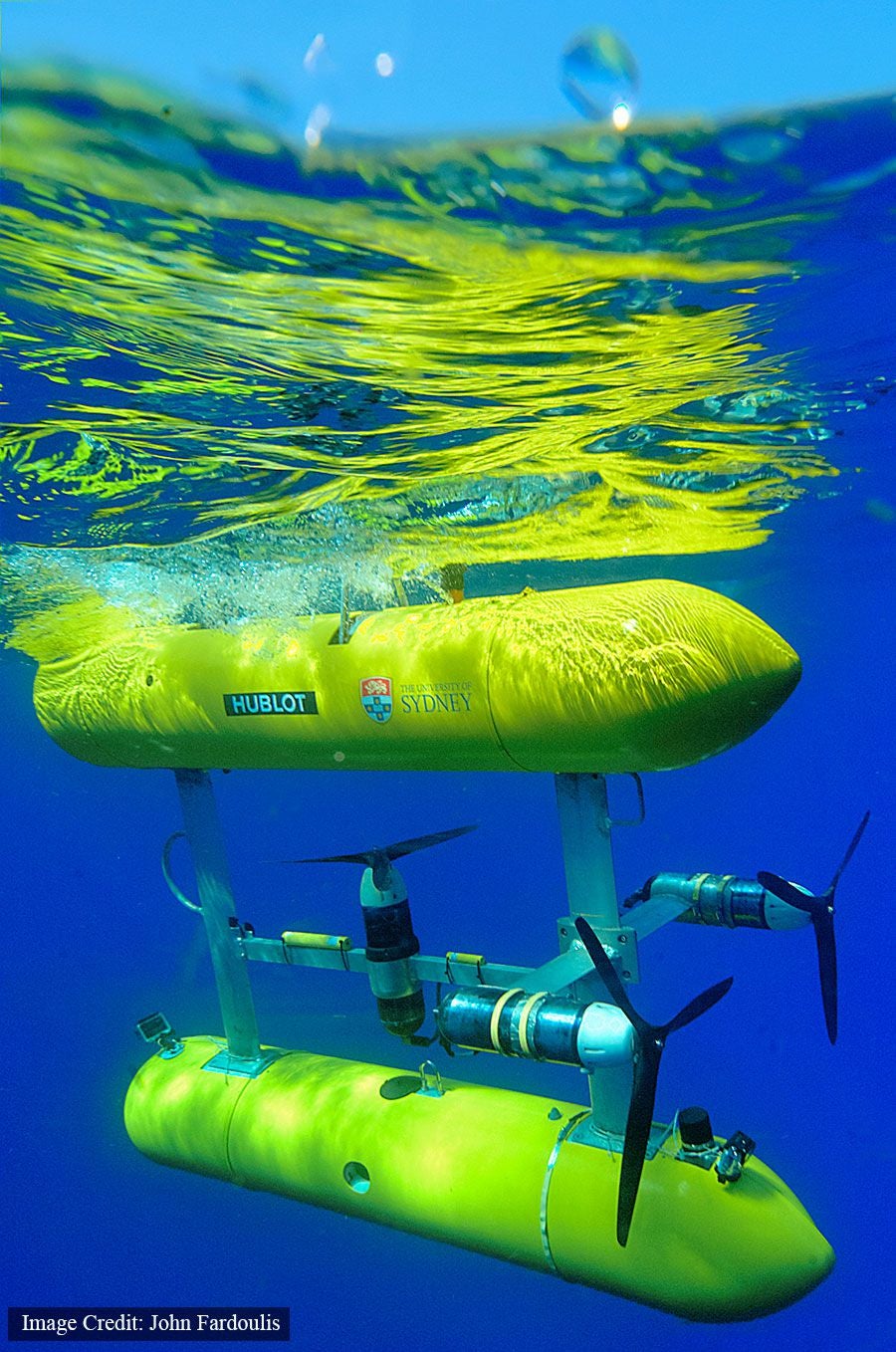

Then there are the autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), operated by a team of engineers from the Australian Centre for Marine Robotics. These robots are the key to mapping the shipwreck in 3D. The Sirius AUV, pictured below, has been sent on multiple trips around the site to record layers of data—including water column measurements and tens of thousands of high-resolution photos—to be stitched together for the map. Sirius has previously been used to monitor the health of Australian coral reefs. It can travel faster and farther than a human diver, even one equipped with jet-powered SCUBA fins.

Of course, some plain old SCUBA diving is taking place around the wreck, too—though the divers are assisted by propulsion vehicles (these resemble small boat propellers attached to steering wheels) and closed circuit rebreathers, which are considered vast improvements over traditional oxygen and carbon dioxide tanks. Oh, and metal detectors.

When Cousteau’s team explored the Antikythera wreck in 1976, divers were limited to ten minutes on the ocean floor at a time. That was enough to offer tantalizing glimpses of what the wreck contained, and to recover some of it, but much was frustratingly out of sight and reach. This year’s cohort of archeologists has the opportunity to get a much fuller picture.