Two years, five countries, and €4,000 later: a Syrian Kurdish refugee’s journey home

It costs €400 ($500) to be smuggled out of Europe.

It costs €400 ($500) to be smuggled out of Europe.

That’s how much Juan Sheikh Muslem, a 27-year-old Syrian Kurdish refugee, paid to leave Spain and return to Turkey on Sept. 25. Over the past two years, Muslem, a chemistry student and one of 3 million Syrians who have fled the country since the beginning of the civil war in 2011, has spent more than €3,000 ($3,800)—his entire savings—paying smugglers in order to reach Europe.

Now, paying just a fraction of that he has returned home.

Since Sept. 29, Muslem has been sleeping in a Turkish mosque in Suruc, just a few kilometers across the border from the Syrian city where he was born, Kobani (or Ayn-al-Arab in Arabic): the city, which could fall in ISIL’s hands any moment, is likely to become theatre to a terrible massacre.

In Suruc, Muslem has heard airstrikes every half-hour, sometimes more frequently. He is finally close enough to home to smell the rising smoke, feel the mortars fall, watch Kurdish soldiers battling black-clad members of ISIL in the distance.

Some 350 Kurdish villages in Muslem’s region have been invaded by ISIL as the terror group forces its way toward Kobani. In the past two weeks alone, more than 300,000 Kurds have fled, fearing for their lives.

At least 150,000 of them have crossed the border into Turkey, where half of all Syrian refugees since 2011 live. Muslem, like many of the refugees who fled earlier, has come back to help the new arrivals.

Turkish-Syrian border, Sept. 2012

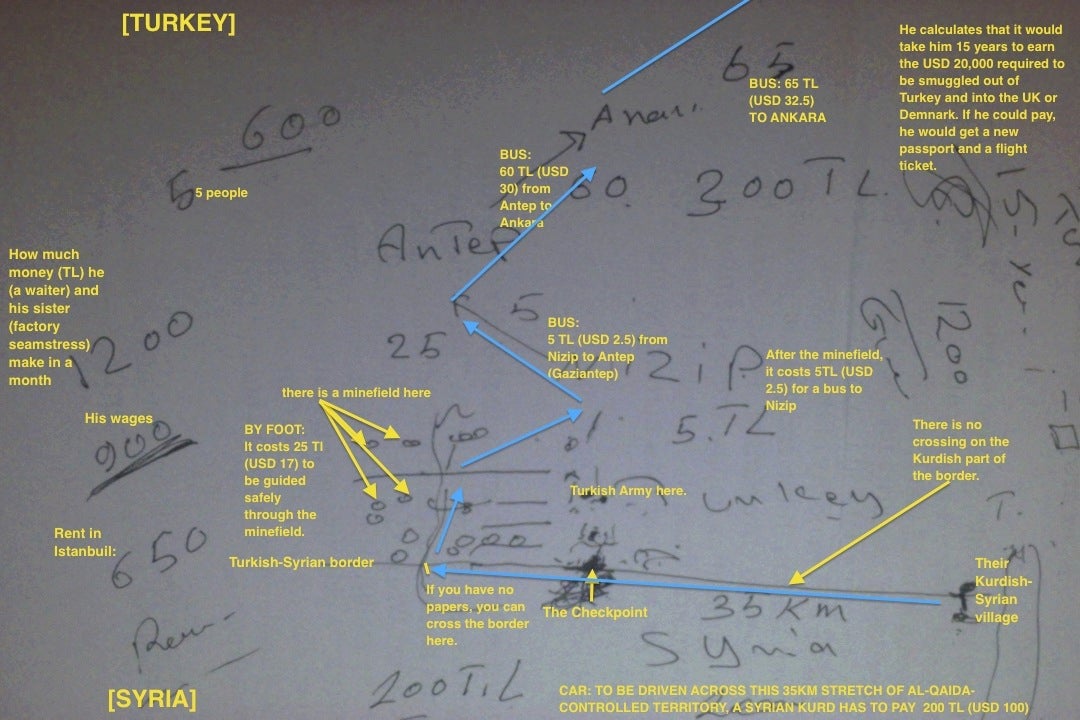

Muslem crossed the same border into Turkey back in 2012, after having been imprisoned for 45 days by the Syrian government for participating in a student protest in Raqqa, which is now an ISIL stronghold. “My home was so close to Turkey but there was no crossing point in 2012, because the Turkish government did not want Kurds,” he says. “So everyone had to go to Jarablus to cross.” At that point in the Syrian Civil War, it cost about $100 just to hire a driver for the 35km ride through al-Qaeda-controlled territory from Muslem’s home in Kobani to the nearest Turkish border crossing. ” There are professional cars that work like taxis,” he adds. “But there was little petrol then in Syria, so it was very expensive.”

Anyone who didn’t have a passport, says Muslem, could then skip the official border crossing and be guided beyond the border on foot through a minefield: “There were 200m of minefields. But the smugglers know how to walk around the mines.” That service, plus fare for an endless series of buses to cross the 1,192km to the other side of the country, says Muslem, was a bargain. “All you needed to come from Syria to Istanbul without a passport was 200 Turkish lira ($88).”

Istanbul, Sept. 2013 to Aug. 2014

In Istanbul, Muslem eventually found work as a trash collector on the Asian side of the city, and then moved into the European side to work at Zaman Kebab, a fast-food restaurant in the Aksaray neighborhood. While other young people planned for the cost of raising children, or buying a first home, Muslem learned to budget in terms of smugglers’ fares. “I want to go to Denmark or England,” Muslem told me in 2013. “But it’s very expensive.”

Black market passage from Istanbul into Europe was (and still is) a luxury reserved for the wealthy. “There are two smugglers that I know who want €10,000($12,628). For €10,000, I could get a passport with a picture that resembled me and a plane ticket to England, Denmark, Germany,” he said.

With his service-worker’s salary of only 900 Turkish lira (about $392) per month, Muslem quickly gave up on his plan of continuing his chemistry studies in the UK. Even with some financial help from his family, he calculated, the trip alone would require at least 20 years of waiting tables.

Headed for Algeria, August 2014

But by August 2014, after two years in Istanbul, Muslem had scraped together just enough money to make a run for North Africa:

- €750 ($938) from Istanbul, Turkey to Oran, Algeria;

- €300 ($375) to be smuggled from Oran to Nador, Morocco;

- €1,000 ($1,251) 25 days waiting in Nador;

- €850 ($1,063) to be smuggled into Melilla, Spain;

- 1 Samsung Galaxy s4 stolen by the smuggler.

Melilla, Spain, Sept. 20, 2014

“At 5am, there are a lot of Moroccan people crossing into Melilla,” says Muslem. “I met my smuggler at the border, and I was squeezed in between them.” Suddenly he was in Spain. His plans did not extend beyond that. Muslem says he walked around Melilla unsure of what to do next. He met a friend on the beach and called his mom from his friend’s phone. But the friend told him that if he left “a footprint” in Spain, he could not move on to Germany or Denmark, referring to the European Union’s policy of processing asylum requests only in the first country where the asylum-seeker arrives.

“And then my mother told me that she and my father had left Kobani and were at the Turkish border,” he says. “And that they needed me to come back.” ISIL’s siege had already begun. Muslem slept that night in a public park, and then decided to return to Turkey. He bribed the Moroccan police €400 ($500) to let him back into Morocco, and paid an additional €600 ($750) for the flight to Turkey. On Sept 25, one month after leaving for Europe, Muslem landed in Istanbul and began making his way back toward Kobani.

Mursitpinar, Sept. 29, 2014

From the small Turkish town of Mursitpinar, Muslem can vicariously live the Kurdish battle for independence from only 700m away. After helping his parents move west through Turkey and settle in Istanbul, he has decided to stay at the border. In a selfie from Sept. 29, he holds up remnants of an ISIL mortar shot into Turkish territory, which killed a fleeing Kurdish civilian.

“These are my people,” says Muslem. “And that is my city.”

The city of Kobani was once supposed to be the capital of a new Syrian Kurdistan, declared independent by Kurdish forces during the uprising against Bashar al-Assad in 2012. It has since weathered sieges by al-Qaeda affiliate al-Nusra and by ISIL in an earlier attack this June. Today, ISIL is back and closing in on three sides. On the Kobani’s eastern front, the terror group is only meters away, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

Fearing a second slaughter like the one in Sinjar, at least 80% of Kobani’s population, not only Kurds but also Arab refugees from Syrian cities Aleppo, Homs, and Damascus, have already fled to Turkey. Hundreds of other Kurds like Muslem have streamed from all over Turkey back to the barbed-wire border, to help their compatriots and witness the last days of their town. They bring water for those crossing the final meter, help carry their possessions and children, and support the elderly. Kurdish men have even been seen crossing the border in the other direction to join the under-equipped Kurdish militia YPG, also known as the People’s Protection Units, to defend Kobani’s city center.

“I am here now because of ISIL,” says Muslem. “Kurdish people need help. But we don’t have enough arms,” he adds, echoing a statement by Salih Muslim, leader of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party before the European Parliament on Sept. 24. “I think Kobani will be lost.”

When it is, he says, he’ll go back to Istanbul and start looking for work again. Any work will do for now.

“In Istanbul, I know a coffeehouse with a green sign where many people wait to go to Europe,” he says. “All you need is money.”