The umbrella movement belongs to everyone who calls Hong Kong home

The ongoing pro-democracy protests mark a new era for Hong Kong, one where locals, expatriates and those of us in between are uniting to fight for a greater cause. The international financial hub of Hong Kong is 92.6% ethnically Chinese, according to the latest census. That leaves 7.4% of us in the “third culture,” who exist somewhere between Hong Kong and our “home countries” struggling to find where we belong amidst the complicated political system, the “one country, two systems” or “special administrative region” that leaves us with gaping holes in our national identity. The last week has changed that.

The ongoing pro-democracy protests mark a new era for Hong Kong, one where locals, expatriates and those of us in between are uniting to fight for a greater cause. The international financial hub of Hong Kong is 92.6% ethnically Chinese, according to the latest census. That leaves 7.4% of us in the “third culture,” who exist somewhere between Hong Kong and our “home countries” struggling to find where we belong amidst the complicated political system, the “one country, two systems” or “special administrative region” that leaves us with gaping holes in our national identity. The last week has changed that.

Hong Kong is my home. I grew up there, I attended school there, my family and friends reside there. My passport says I am from Hong Kong, but my ethnically Indian appearance does not. I am in the same position as 751,182 other non-Chinese residents who consider Hong Kong home, but seem confined to our own interpretations of the city. We operate within clearly defined clusters: the international school community, the Filipino community, the American expat community. Some call Hong Kong home for a short spell, while for others like me, it is the only home we have ever known. Yet none of us have ever been able to assimilate into the mainstream. We belong to Hong Kong, but we have never been able to fully feel as if Hong Kong belongs to us.

It is difficult to pinpoint what separates us from the Chinese majority: minority status, language barriers and a divisive education system are a few of the many explanations. But the divide is pervasive and pernicious. In school, we learned about British colonialism, ancient China, Pearl Harbor—events that tangentially influenced Hong Kong’s history without any real understanding of how to tie those events together to understand what Hong Kong is. After explaining to foreigners that no, Hong Kong is not a part of Japan, I proceed to describe our relationship to China, spewing the “one country, two systems” party line without really understanding the entrenched implications. At my college graduation, I shifted uncomfortably as all my peers stood up, caps to their hearts, to sing the American national anthem. Hong Kong has no anthem of its own. I often joke that the only thing Hongkongers are patriotic about is our skyline. Last week, we flipped this truism on its head.

Till now, we lived in a laissez-faire bubble where we simply assumed the government has our best interests at heart. Finally, we can move away from the political apathy that has for so long defined our citizens, and towards a political spirit that incenses and impassions us. Although we are fighting for universal suffrage, ironically, only 20% of eligible voters have thus far actually participated in elections. The protests have birthed an unprecedented political spirit that invigorates our entire population. Journalists have reported that the Hong Kong protests have given rise to a new political generation.

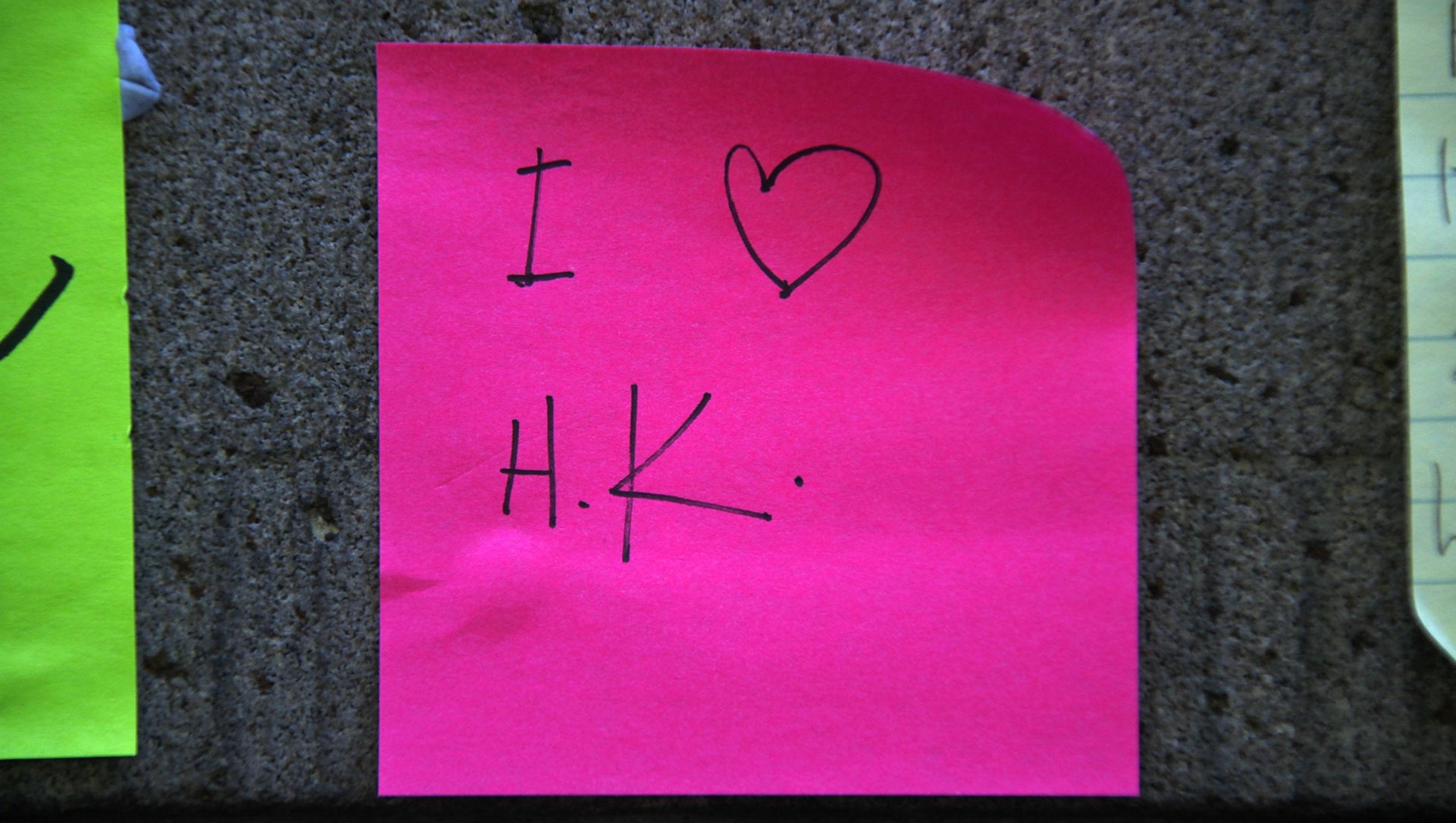

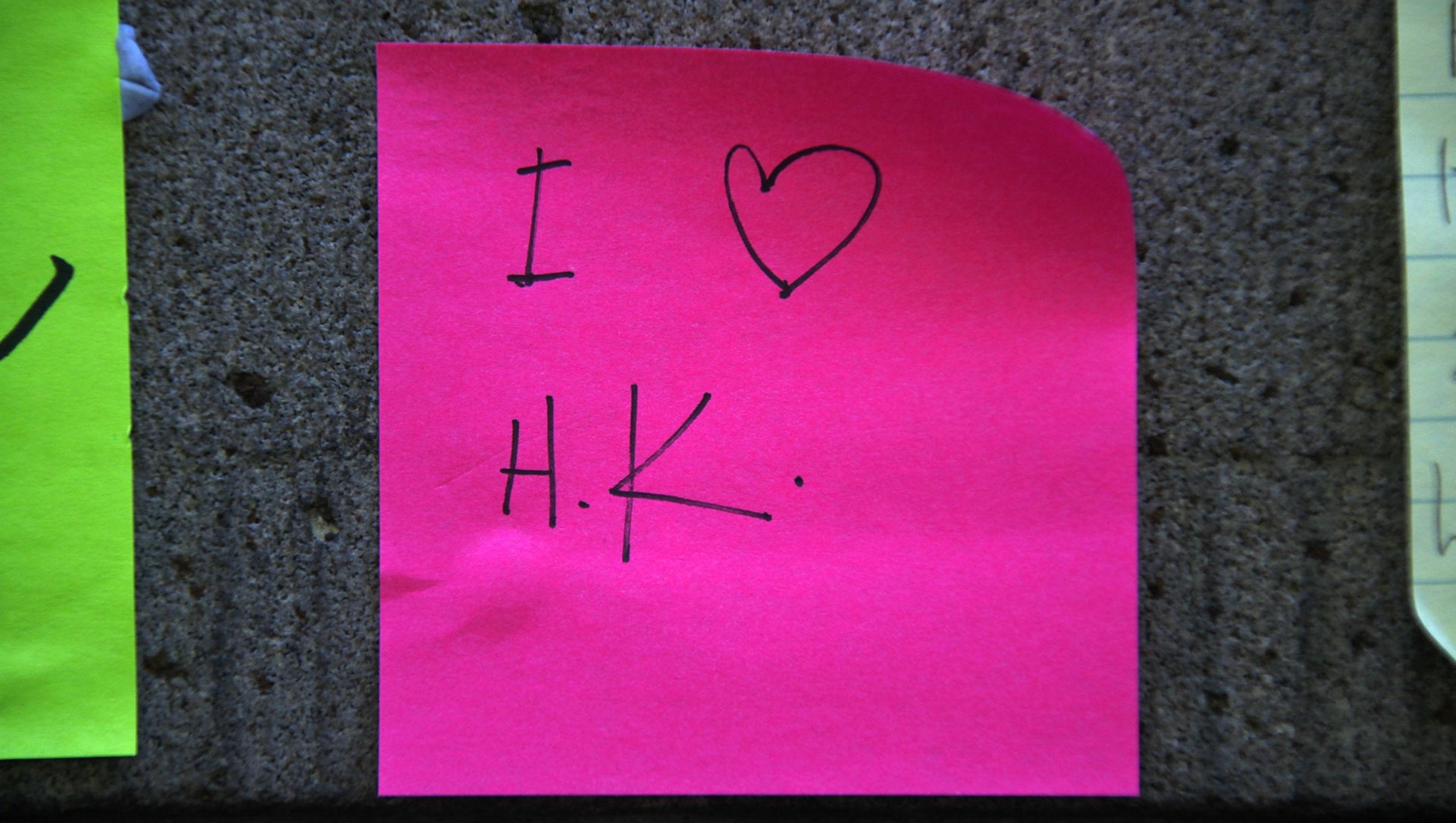

But it is not simply age that divides us. The Hong Kong protests have given rise to a new political mass, one that incorporates people of all races, demographics and backgrounds, who have all sorts of varied connections to Hong Kong. Social media has created a web of people and information, united by the pride, hope and optimism that these revolutionary events could bring upon our city. Facebook is flooded with messages of support and profile photos changed to an image of a yellow ribbon against a black background. Through Whatsapp, WeChat and Snapchat we’re sharing in our extended network photos of deserted roads, videos of chanting on the street, and wishes that we will be able to forever change the fate of our city. A renewed wave of patriotism has swept the streets of Hong Kong and taken us all in its tide. If we were to vote right now, voter turnout would be at an all-time high.

As Hana Alberts so aptly puts it, Hong Kong’s diaspora isn’t simply “limited to Cantonese people in Chinatowns across the continents, but instead broadly inclusive of everyone who’s called Hong Kong home.” The protests have broken down the cultural silos that have persisted for so long in Hong Kong’s multicultural population. Our community has become greater than our differences.

Recent headlines have commented on the many freedoms that separate Hong Kong from China: freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and freedom of expression, but we are experiencing for the first time a new freedom that is unique to our “third culture:” freedom of identity. The very liberties that separate us from China have finally given us the freedom to be who we really are: Hongkongers, first and foremost, striving together to fight for our rights.