How mainstreaming bitcoin makes it more like Wall Street

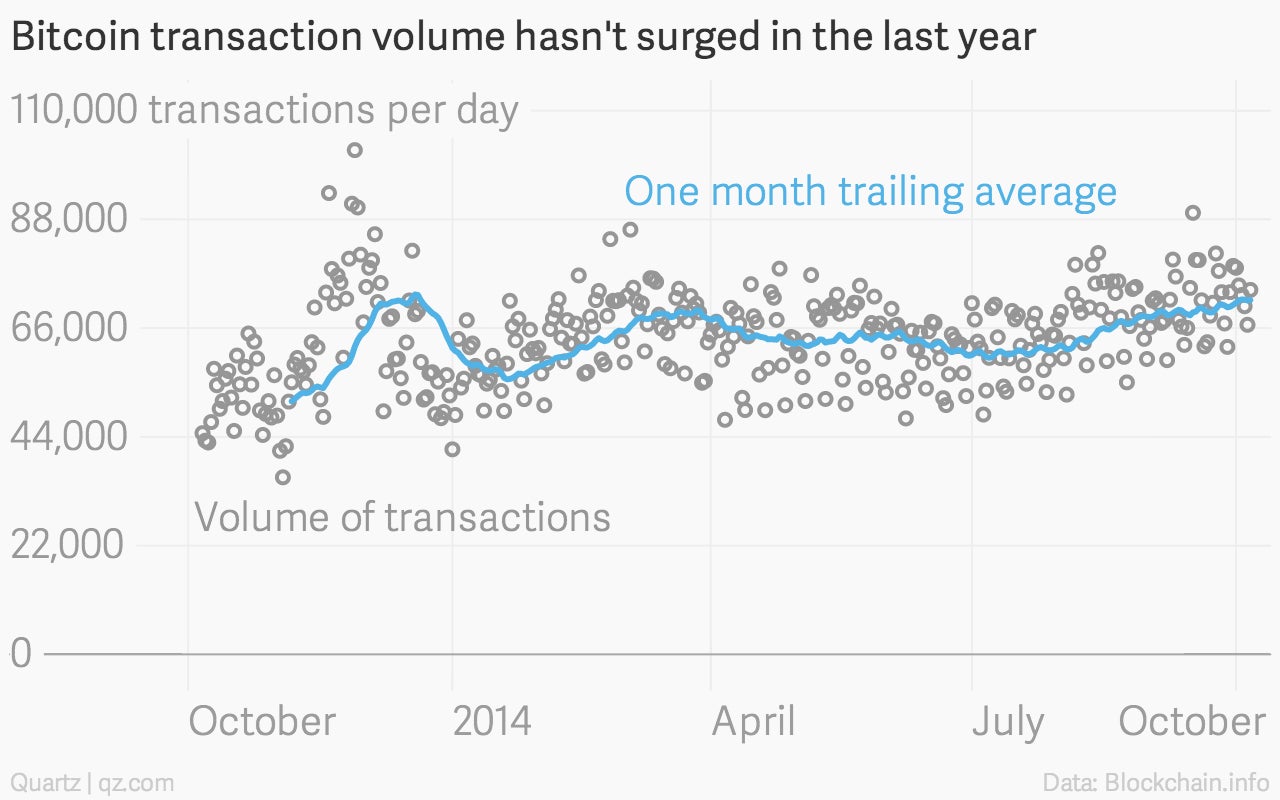

A few days ago we noted that it isn’t a good sign for the nascent bitcoin industry that transaction volume—a decent proxy for use of the currency—has been pretty stagnant lately:

A few days ago we noted that it isn’t a good sign for the nascent bitcoin industry that transaction volume—a decent proxy for use of the currency—has been pretty stagnant lately:

That data is surprisingly accessible thanks to the way bitcoin works—all transactions are recorded into the blockchain, part of the ever-expanding log of computational problem-solving at the heart of the crypto-currency’s technology. But one reader noted an important exception: This doesn’t measure an increasing amount of bitcoin activity going on “off the chain.”

How does that work? Well, more and more bitcoin services are hanging onto their users’ bitcoins and executing transactions behind the scenes. Think of it like a bank: The money in your checking account isn’t actually in some separate box at your financial institution; the bank keeps track of what’s yours by noting the amount in its books. If you transfer money to another customer at the bank, the banks just adjusts its records. Start-ups like Coinbase and Circle that are attempting to make bitcoin mainstream do much the same thing with transfers between customers.

That’s one important way that increasing bitcoin use wouldn’t show up in the chart above. Other reasons for doing off-the-chain transactions include cost (you don’t have to pay the small fee needed to verify transactions that are in the blockchain) and speed (creating blocks in the blockchain can sometimes take a while, although Gavin Andresen, the chief scientist at the Bitcoin Foundation and an adviser at Coinbase, has proposed a major expansion of bitcoin’s processing capability to allow it to scale up more efficiently).

Off-the-chain transactions remain controversial in the bitcoin community because they rob the system of its great advantages: Instead of relying on a decentralized network to securely and transparently verify transactions, the records are centralized at an opaque point and rely on someone else’s security. You need a lot of trust for that, as we learned during the Mt. Gox crash: The reason people lost bitcoins when the company crashed is they relied on Mt. Gox to hold their money for them, rather than following the somewhat cumbersome procedures needed to secure bitcoins themselves. Mt. Gox got hacked, wound up insolvent, and anything that was off the chain disappeared.

Which brings us to Marc Andreesen, whose venture capital firm led a multimillion-dollar investment round in Coinbase. In a recent interview with Bloomberg on the promise of tech innovation to improve banking, he extolled bitcoin’s virtues:

In a bitcoin world, things like the Target hack are not possible. The way a digital currency works is that it lines up the incentives to protect yourself with the consequences of failing to protect yourself. Bitcoin is a digital-bearer instrument: If you have the numbers on the coins, you own the coins. You can make payments without having to give any information about yourself, and everyone can double-check their transactions. If someone hacked into Target, they would be able to steal all of Target’s money—but they wouldn’t be able to steal your money.

He’s right—but you don’t have the numbers on the coins when you’re relying on off-the-chain transactions. You aren’t using a digital-bearer instrument, the same as a credit card is not a bearer instrument like a dollar of cash. When consumers and merchants use companies like Coinbase and Circle, they are relying not just on bitcoin’s security and open ledger, but on the security measures taken by the company to protect its private database. Even if the security technology is amazing, it makes off-the-chain transactions no different, conceptually, from what any Wall Street bank with a payments business uses when processing payments for a company like Target. Except, as Andreesen notes, it dodges the costs—and benefits—of regulation.