How carpooling turned a decade-old startup into a multimillion-dollar prize

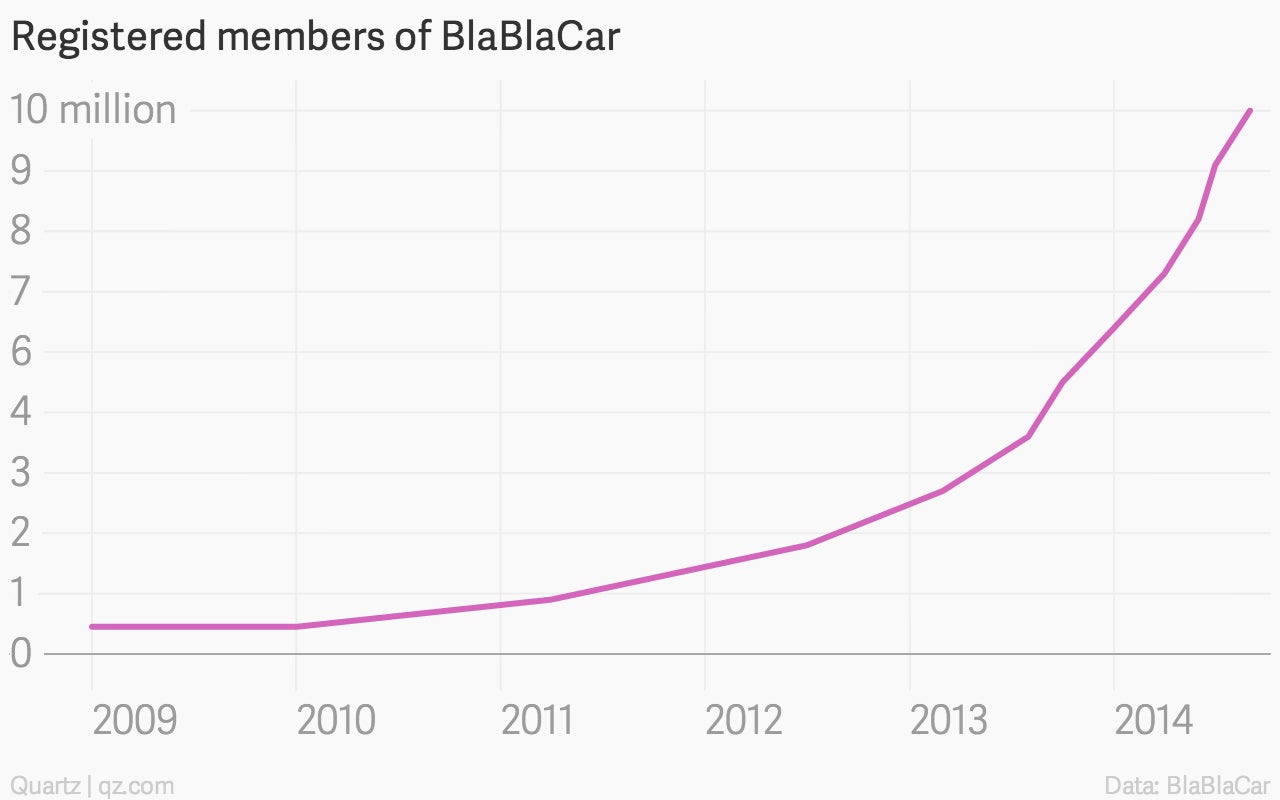

Early last year, fewer than 3 million people had signed up to use BlaBlaCar, a ride-sharing service from France. By September this year, the number was more than triple that, having just passed 10 million. A fifth of those use it every month. “I think we can build a 100 million or 200 million strong community in the next three years at the pace we’re growing,” says Nicolas Brusson, a co-founder of the start-up.

Early last year, fewer than 3 million people had signed up to use BlaBlaCar, a ride-sharing service from France. By September this year, the number was more than triple that, having just passed 10 million. A fifth of those use it every month. “I think we can build a 100 million or 200 million strong community in the next three years at the pace we’re growing,” says Nicolas Brusson, a co-founder of the start-up.

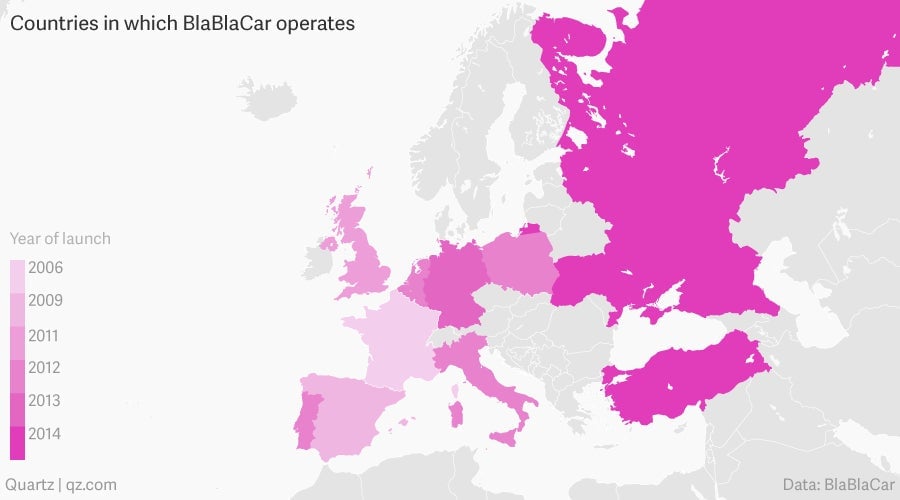

BlaBlaCar’s growth is the result not of a viral campaign or clever social media marketing, but a very old-economy strategy: acquisitions. In the past three years, the company has bought up companies in Italy, Poland, and Ukraine (which also operates in Russia). That has allowed it to expand its network of rides rapidly and to sign up millions of new members in a hurry. “The growth explosion we’ve seen is the result of seeds we planted since 2011,” says Brusson. BlaBlaCar is now present in 13 countries, three of those added just this year.

Not quite Uber or Lyft

BlaBlaCar is based on a simple proposition: Lots of people need to get from A to B. There are also lots of people driving from A to B in empty cars. Match them up and you make a market, facilitate a ride, save money for both the driver and the passenger, help the environment by carpooling, and perhaps make a couple of dollars, too.

There are restrictions. Unlike the more familiar ride-sharing services such as Uber and Lyft, BlaBlaCar does not operate within cities. Prices are fixed according to the cost of driving, and drivers cannot charge more than the BlaBlaCar-approved upper limit. This works in everybody’s favor: Rides remain affordable even at times of high demand, and the drivers are protected from regulatory, legal or insurance problems since they make no profit. It is not a commercial service. But it can often be fun: Lydia Hunt, a British student who used BlaBlaCar for her once-in-three weeks drive home from the other end of England, says her brother once used BlaBlaCar and was picked up in a Ferrari.

BlaBlaCar makes money by charging a small fee, but it rolls it out gradually, only once people have become accustomed to using its service. At the moment, BlaBlaCar only charges a fee in France, where it launched in 2006, and Spain, which it started serving in 2009.

Airbnb, RyanAir or something else

It sounds simple in theory. Connect some drivers with some riders, buy up other companies doing the same thing in other countries, and repeat. But the dynamics are different in different countries, explains BlaBlaCar’s Brusson. In western Europe, BlaBlaCar is similar to other “sharing economy” services like Airbnb, where people simply use it to cut costs on expensive train travel.

But in other countries, notably Russia and Turkey, Brusson says he is seeing different trends emerging. In Russia, people use the service mostly to get around within 200 miles of Moscow, especially at the weekend. In Turkey, where the transport network is less extensive than in western Europe, it allows people to travel routes they otherwise couldn’t. In that sense, it is more like RyanAir, which created demand for travel to places that people did not know they wanted to go to until they saw cheap flights advertised. (Brusson argues the analogy is not quite right since BlaBlaCar isn’t creating the routes, merely facilitating them.)

And in India, where the train network is extensive and cheap, BlaBlaCar has another proposition yet: spontaneity. Indian trains tend to fill up quickly and last minute reservations are generally impossible. The company’s selling point when it launches in India will be that rides are available up to a day or two in advance of a trip rather than the weeks and months of forward planning required for train tickets.

From pasta days to salad days

In July, BlaBlaCar raised a massive $100 million dollars from a clutch of venture capitalists. Brusson says he only set out to raise €20 million ($25 million) in order to expand to Brazil. But Russia has launched a few months earlier and had grown to a quarter of a million members. “We realised, jeez, there is more demand here in Europe. So we extended the fund raise to $100 million and started to build a new business team,” he says.

Turkey was first on the new, closer-to-home list, though both Brazil and India are very much in the works. Philippe Botteri of Accel Partners, which has invested in BlaBlaCar over two rounds, says BlaBlaCar is now bigger in Germany than carpooling.com, its main rival.

The United States, however, is unlikely to follow any time soon. A system such as BlaBlaCar’s needs good intra-city public transport to get passengers to the pick-up and from the drop-off points, which most American cities lack. Instead, Brusson sees a future where BlaBlaCar’s network could diversify into all sorts of other businesses: deliveries, insurance products, perhaps even telematics. Brusson used to be on the board of Octo Telematics, the world’s leading telematics firm.

BlaBlaCar’s growth may be soaring now but it wasn’t always this way. The company’s birth is a bit muddled. Its first version, in 2004, was like a classified site. The company was officially formed in 2006. And it was only in 2009 that the team hired their first employee and moved into their first office. In 2010 BlaBlaCar raised its first cache of funds, €1.2 million from a Paris angel investor, and real growth only started in 2011. But 2009 was the turning point, says Brusson. “Until then, we were just eating pasta.”